PUMLA DINEO GQOLA

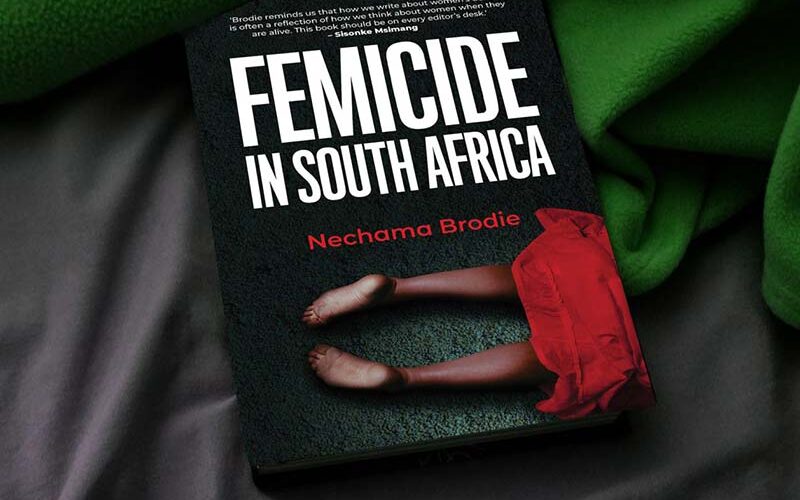

FEMICIDE is a South African preoccupation. News headlines have made names and faces familiar with such frequency that only the most delusional among us deny that women are being killed at an alarming rate. Nechama Brodie’s Femicide in South Africa enters this fray to raise the quality of public debate on femicide and illuminate why a proper diagnosis of the situation remains so elusive.

Many raise the country being broadly homicidal as one way of putting femicide into context. But generalities only deepen the crisis because femicide “carries such distinct features that, if we were to try and understand or profile these killings only in the context of male homicides, we would miss the point entirely”.

Brodie’s book delineates these “distinct features” and shows how greatly they matter. She deals with much of the misinformation around the issue, including “the state’s continued reluctance to take responsibility, even going as far as to obscure crime data on more than one occasion”, the ways in which femicide is reported on, myths about how and where violence occurs, political agendas such as white right-wing claims of a white genocide and the improper use of statistics.

Types of femicide and our inadequate grasp of them are illustrated when Brodie painstakingly teases out, for example, that a fifth of all femicides are femicide-suicides. Femicide-suicides are when a man takes his life immediately after killing his woman partner. Brodie shows how femicide-suicides are much more likely to be perpetrated by a professional white man with a legally owned gun. And that although most femicides are by the victim’s partner or former partner, they make up less than a third of femicide news stories. Under apartheid, the “unrelenting” instances of femicide-suicides mostly involved a member of the police force as the perpetrator, and sometimes as the victim.

But “media reports on crime usually have little resemblance to the reality of the crime itself, although at the same time, news media is where most people learn about crime, particularly violent crime, and how to understand it.”

As such, Brodie’s book is concerned with how femicide is represented and portrayed in the media. As author Sisonke Msimang says in a shout-out on the cover, this “book should be on every editor’s desk”. It is a book linked to, but broader in scope than Brodie’s doctoral thesis – and one that is much more ambitious in its aims.

History and language

Femicide in South Africa provides continuities in legal, media and societal responses to femicide stretching back several decades. Brodie makes no apologies for mindfulness of the past, taking history much more seriously than as mere background. Instead, she wants to understand the history of femicide and the language used to speak about it.

Consequently, there is much to delight the student of history in the author’s treatment of femicide’s South African and global past. For one, we understand “domestic violence” as a term that meant something completely different under apartheid, rendering it impossible to speak about it in ways that denoted gendered violence before 1994. Brodie also points out that the feminist language so crucial in combating femicide, rape and sexual harassment has only developed recently.

South Africa-born Diana Russell, who died at the end of July, coined the term “femicide” in 1976 as a way of speaking about women killed simply for being women. Coining the term at the International Tribunal on Crimes Against Women that year was a political innovation, in the work that the word does, that forged a way to speak about gendered violence and laid out a path for further intellectual debate. She said, “I hoped that introducing this new concept would facilitate people’s recognition of the misogynistic motivation of such crimes.” Her gift is that we use the term today as though we have always had it in our vocabularies.

Russell generously agreed to meet us, a group of feminist activists at the University of Cape Town, in 1991 on one of her research trips. This was two years after the publication of her invaluable tome, Lives of Courage, which features interviews with 24 South African women activists. It is a text that is still valuable to feminist researchers today.

Even then, as undergraduates in our late teens, we used the feminist vocabulary against gender-based violence as though it had always been available to us, unaware of how much had been achieved in our childhood by women like the scholar-activist in our midst. Brodie insists on signposting some of the steps taken to develop a language around femicide and offers her terminology as a contribution to feminist research. Tracing the lineage of feminist vocabularies – and how recently some of the terms relating to femicide have been coined – is important as a counter against an ahistoricism that has snuck into how some feminists talk about gendered violence, and to find ways of forging pathways for this work to continue.

The politics of naming and data

Brodie’s use of femicide deviates somewhat from Russell’s. Where Russell distinguishes between “female homicide” and “femicide”, Brodie uses the two interchangeably. This enables her to deploy the terms as analytical categories to make sense of the data she mines. Their naming choices are political in terms of the ways they both use and develop language to speak about gendered violence.

To arrive at her sample size, which is in excess of 5 700 news articles on 408 femicides, Brodie focuses only on adult and teenage women. She never lets her reader forget that 408 femicides, the total covered in the media during the years under study, is a mere 20% of the 2 587 homicides reported to the police during that period. And she reminds us that this 20% is not representative of the patterns of femicide.

Dreading reading a chapter dedicated to why numbers matter, as this seemed largely self-evident, I found the arguments Brodie makes for focused attention on the numbers are pleasantly surprising. Raw numbers are remarkably unhelpful and subject to widespread misuse by apologists and others. Brodie shows us how numbers on femicide are misused when inattention takes their value for granted. She says numbers are useful in shaping practical interventions in the femicide crisis.

This fascinating and necessary commitment to practicality is also evident in the kinds of feminist activism Brodie is impatient with, especially in her final chapter. This chapter, the least convincing in the book, offers a critique of contemporary feminist forms that eschew the practical. I am not as convinced as she is, for example, that a call for the use of intersectional legal mechanisms for gender-based violence is impossible to translate into something tangible because it is too abstract.

Intersectionality, even though often misread as being about identity, was coined specifically to deal with the judiciary’s failure to make proper sense of gender-based violence against black women. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intervention, as a law professor and legal theorist, was into practical legal procedure. It may have come from another place, but even Russell first spoke of femicide in Belgium, so we know concepts travel. Brodie’s attachment to clearly articulated and practical demands from the state may portray greater optimism in the state and judiciary’s ability to deliver justice than that held by the feminists whose strategies irritate her.

Femicide in South Africa is a well thought out study of femicide. It challenges readers’ understanding of the phenomenon, has implications for the study of gender power, violence and femicide, and could be an invaluable tool in the hands of police officers investigating such crimes. Brodie offers many wonderful rebuttals to the highly circulated but deeply flawed solutions that have been proposed for ending femicide in the country.

This is a much bigger book than it purports to be. Brodie brings her extensive experience in shaping language as a journalist, novelist, fact-checker and academic to Femicide in South Africa, a layered book on a difficult subject, heavyweight yet readable for a general critical audience. – NEW FRAME