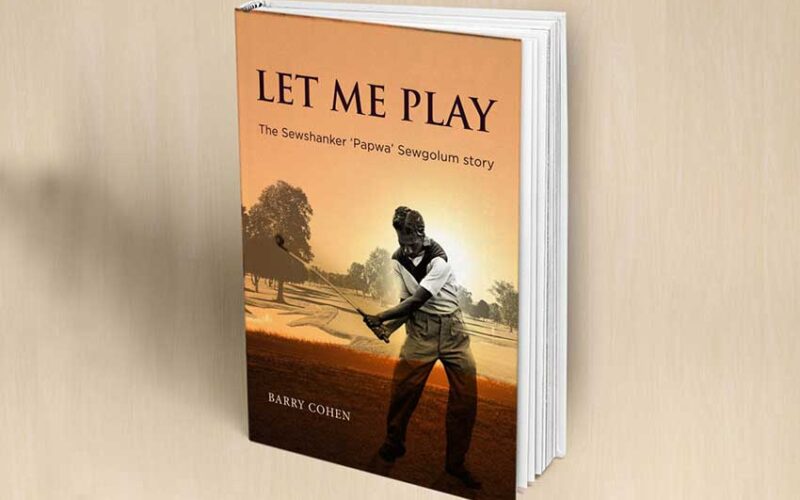

BARRY COHEN

SEWSUNKER “Papwa” Sewgolum began playing golf with a syringa stick but went on to win the Dutch Open and several South African tournaments before the apartheid government banned him.

Papwa, the early days

Papwa Sewgolum’s parents had come to South Africa in 1860 along with many other indentured Indians from North India via Calcutta to work in the sugarcane plantations on the Natal North Coast. They hoped to make a new life in the land of milk and honey, and prosper, and to get away from their grinding poverty and punishing colonial taxes (which would eventually lead to Gandhi’s march to the sea against the salt tax) much like Ramnath Bambata’s grandparents.

His father had already told Papwa stories about the great Mahatma Gandhi, one of two Black lawyers in South Africa who previously lived down the road 20 minutes away from Riverside in Phoenix Settlement, and who subsequently returned to India to confront the British colonial government. If only someone would do this for the South African Indians.

Papwa, meaning “small” or “darling child” as he was known, of Indian descent, was designated as “coloured” in the country’s prismatic social structure. He was born in December 1928 to a mother, Parvathy, who was going blind, in a tin shanty in Riverside, in a part of the world with a history of oppression. Papwa lived among the poorest of the poor in the Riverside area. They lived very modestly.

This was about 1km from the all-white Beachwood Golf Club, and two years after the opening of the first Black golf club, the Durban Indian Golf Club at Curries Fountain. It was in Natal that Southern Africans experienced their first taste of systematic segregation under the British colonial “Shepstone system”.

Riverside was situated in Durban North with unparalleled views across a magnificent green belt, stretching from the Umgeni River mouth with its abundant bird life on the Umgeni Estuary, across the Indian Ocean and towards the beachfront beyond. It was a mere 12 minute walk to the beach, set 1km from the banks of the Umgeni River, yet close to the city centre of Durban.

Pounding surf crashed on the shore not far from the little shack which he called home. The tropical air was humid as Papwa and his father left for their late afternoon fishing along the Umgeni River to supplement his meagre wages.

Papwa held the greaseproof paper with their bait, dough made from flour and water, and his father explained that by placing some dough in a bottle in the water, it would attract smaller fish to swim into the bottle and these could be used as bait for the bigger fish.

Just then they heard a shout of “fore” as a white ball crashed into the colourful bougainvillea bush close by. His dad retrieved the ball, only to be accosted by an elderly red-faced man holding a stick as he came crashing through the bush wanting to know whether the “coolie” was stealing his golf ball.

Such was his introduction to the game of golf and it piqued Papwa’s interest. When the man was told that the ball had nearly hit his little boy, he gave a half-hearted apology and gave his father a tickey as a reward for finding the ball.

While fishing, and in the quiet moments, his father explained the game of golf to young Papwa, and how the great Ramnath “Bambata” Boodhun, a Hindu man like them, who started out as a caddy boy, and lived in Berea across the Umgeni River about 10 minutes from Riverside, had gone to play in the white man’s British Open at Muirfield, the greatest tournament in the world. Also, when he was a bit bigger, he too could go and carry the white man’s bag of golf sticks and earn some money.

Papwa immediately told his father that he would be as great as Bambata, even greater and that he too would go and play in the Open. His father looked down at his little laaitjie boy, and smiled, proud to have his son tagging along for company. “Little boys are like dogs,” he thought, “they got to be taught”, as he started to whittle away a small syringa tree branch.

Finding a pebble, his father demonstrated how to hit the “ball”, and how to putt. Papwa was intrigued. Later, they made their way back home and his father pointed out the Durban golf course, and the strange white men as they hit the white ball into the bush, retrieved it, and then hit it back into another bush. To Papwa it seemed funny, and excitedly he described the scene to his mother. The strange men with canvas bags, and strange sticks which looked like thin bamboo shoots, some with knobs on them, hitting this little white ball trying to get to roll it into a small hole with a flag, on what appeared to be a freshly mown lawn, clapping each other on the back, while Indian boys carrying bags had to keep very quiet and not talk at all because this would make the white man very angry, as they watched and exchanged money among them at the end of the hole. And Papwa also learnt many words of these white men’s language, such as Damn, Hardlines, Putter, Bunker, Goodshot, and so on.

Young Papwa Sewgolum had witnessed this unique sport which was sweeping the colony, a game that had commenced in South Africa with the first member golf club in 1886 (or possibly earlier at Cronstadt in 1878). This was the Cape Golf Club (later Royal Cape GC) at Cape Town, although prior to this there had already been three-hole golf courses constructed at military bases in Port Elizabeth and Natal by British soldiers to keep themselves occupied.

It may have been a world away for a poor Indian boy, but Papwa was fascinated, and the seed was planted. He too would one day stride those fairways followed by hordes of supporters with the sole aim of getting the white ball into the hole. His mother smiled at his babbling, and then prepared their small spiced fish supper and it was time for bed.

While his father played football for the local Indian team, Papwa would sneak away, squirming his way through the Beachwood Golf Club’s fence and watch these strange white men at play, waiting for the opportunity to “find” a golf ball for his own use. He had his father whittle him a syringa stick putter, and after placing tin cups in the sandy ground at home, he challenged his father and little brother to a “game of golf”.

Every night he putted over his “green”, placing balls around the cup, first from two-feet, and when he had holed these, he would place them once again around the cup, but this time a foot further away, until he had sunk all these putts before extending further back.

Like other Indian boys, he also fashioned golf clubs from branches and rolled iron, and taught himself to swing with what was to become his famed cross-handed grip (hands positioned the opposite way to the traditional grip) to get the ball quickly into the air due to the light weight of his “clubs”.

This grip had become popular with the other caddies throughout the country for the same reason, and was called the “caddy grip”. Papwa’s future provincial rival, Ismail Chowglay would also use this grip with much success in Cape Town, and later Vincent Tshabalala, who was destined to win the French Open, used this grip with his long irons.

As he did not go to school, he sometimes played “golf” with his friends after a midday swim in the Umgeni River. By now, their clubs were mid-ribs of palm leaves and their golf balls palm nuts. Three sticks were set up around the river bank, indicating where the holes were: But it was their mannerisms – obviously modelled on their pet “Bwana” – their power drives, the wrist play, the disgust after a bad shot, the putting stances. Everything, and even after all the practice swings, mimicry, etc, they cracked the old palm nut as to the manner born, with perfect timing, as far as any man born of woman could hit a palm nut with a palm-leaf mid-rib, on riversand, in the same set of circumstances.

As his hands were still tiny, Papwa’s hands were separated with no overlapping or interlocking of fingers to assist the wrist in holding the club. He swung the “club” back past parallel almost bouncing off his right shoulder, with his hip fully turned, and his left heel raised, then with his trademark dip, as he bent his knees to get to it, he swung downwards as hard as possible, often falling back onto his right foot, which later became a part of his style, and whipped his right hip through the swing to generate the clubhead speed.

His putting style was interesting with his left foot leading his right, helping to counteract the wind and steady him. Given his grip, he would “pop” the ball, putting down into the stroke.

His grip was an unorthodox way of holding the club with a backhanded hold, hands left to right, an unconventional hold sometimes found in geniuses (many top golfers today use Papwa’s cross-handed grip for putting, even chipping, but virtually no one uses it today for all shots). “I believe a man should swing a club the best way he knows how,” Papwa told Golf Digest in 1964.

Before long Papwa had found an old broken wooden-shafted rusted club in the bush alongside the fairway, which his father cut down for him as it was far too long and heavy, and with the few balls he had found, Papwa began playing whenever he went to watch his dad fishing. (Later the famous Seve Ballesteros and Lee Trevino would start out as caddies with one club with which they would learn to play.)

And he sneaked onto Durban Golf Club to watch the great Bobby Locke win the 1938 South African Open (he would go on to win over 80 tournaments including four British Opens and nine South African Opens, that is every time he entered, until he virtually lost the sight of his one eye in a train-crossing accident), the greatest putter in the world. In 1945 he played 1 800 holes of tournament golf and never had a three-putt.

First, he would look behind the hole, then from side to side, and finally from behind his ball to make sure of all the twists and turns, knowing the ball would also move away from any mountain or koppie and towards water. He would approach the hole examining the way the grass was leaning; if it was leaning towards the hole, it would be a fast putt, and a slow putt if it was away from the hole. Finally, he looked at the position of the cup in the hole, and if the hole was more upright at the back he could hit the putt just a little firmer.

He would crouch down on his haunches behind the ball, twirling his famous wooden-shafted blade putter until he could actually visualise and see the path along which he needed to putt the ball. Now standing over the ball with his right foot behind the left, he took the blade back in a curve following the line of his feet, closing the face, pressing forward he brought it down onto the ball, minimising the bounce as the blade made contact and conveying the spin onto the ball.

He gave the impression and the false hope to many an opponent that he would hook the ball offline, but he always hit it in the middle of the putter in the right direction, and magically, it would hook as it made its way into the hole. Nobody, no one ever hooked their putts, yet Locke was the greatest putter the world had seen, and he viewed the putt as having three opportunities to go into the hole, from the left side, the right side, or directly into the hole. And so Papwa learnt, and his confidence and concentration grew.

Then suddenly his father, his role model, passed away in 1938 when he was just 11, leaving Papwa as a breadwinner. His sister helped around the house, but Indian women did not go out to work, so he had no alternative but to go out and try and earn some money together with his older brother, to support his blind mother, sister and younger brother.

Eventually, he found work as a thread-cutter in a garment factory in Prince Edward Street in Durban. But three years later, to make ends meet he was earning money caddying at the Beachwood Country Club – caddies were also allowed to play on Monday when the course was “closed”. (Indians were not allowed to play on the course as a de facto form of segregation which had become institutionalised throughout the country.) It was here that Papwa learnt the art of golf.

“I had no love for the game of golf when first I started. I was 13, and my father had died leaving me to help my mother and younger brother. My stomach was my introduction to golf, and at seven shillings a week I wasn’t able to fill it often.”

So Papwa had learnt to play, first by knocking pebbles along the beach shore with a stick, and later by caddying for and watching the rich white folk hack around the golf course. Sometimes giving advice but usually having to remain quiet when they admonished him for their poor shot-making.