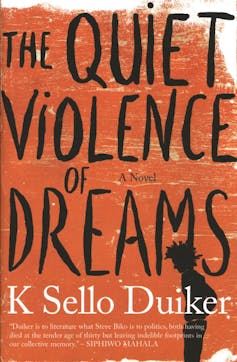

THE South African novelist K. Sello Duiker would have turned 48 on 13 April 2022. Since 2005, when he took his own life at the age of 30, his importance to the body of African literature has become even more evident. His works have been republished within and outside South Africa and continue to be the subject of both academic and social media discussions. Testament to his legacy, the South African Literary Awards gives a prize in his name every year to writers under 40.

Duiker is considered a key voice in what some scholars refer to as South Africa’s post-transitional literature. This is writing after 1994 brought democratic elections to the country. A major characteristic of this writing is the emphasis on the porosity of identity boundaries: that people can be more than just one thing at any given time. It contrasts with earlier grand narratives of political resistance which didn’t recognise the diverse and changing contexts that contribute to identity.

Duiker focused on marginal figures in society: the street child, the sex worker, the queer African, the struggling immigrant and so on. One or more of these appear in each of the three novels he wrote. Readers of his award-winning Thirteen Cents (2000) will attest to the haunting power of his exploration of coming of age in post-apartheid Cape Town as a street child. Azure, the 13-year-old blue-eyed black protagonist of the novel, is an orphan forced to fend for himself in a ruthless city still riddled with the unrelenting inequalities of race. The boy, however, possesses insight into a supernatural realm that offers possibilities beyond his confining circumstances. Some readers consider Azure’s dreams and visions as evidence of a psychotic break; others see it as Duiker’s masterful combination of hyperrealism and magical realism.

Duiker’s next major book, The Quiet Violence of Dreams, (2001) contemplates this ambiguity of madness. It is the story of Tshepo, a young black man who, like Azure, lives in Cape Town, and, at some point, resorts to gay sex work for survival.

Tshepo, however, is from a middle-class family, cultured and artistically inclined. Although he drops out of college and endures some financial hardship, he is never destitute. He moves in the company of upwardly mobile South Africans in an interracial consumerist urban culture. But Tshepo bears the scars of childhood abuse and violence at the hands of gangsters. He suffers episodes of mental distress that result in his admission to a psychiatric hospital.

The question of how to define madness recurs across the works of Duiker, as he experienced a mental breakdown himself.

In a recent journal article I analysed The Quiet Violence of Dreams as a novel concerned with madness and psychiatric incarceration. Most of the studies on the novel focus on its same-sex intimacy. But this undermines Duiker’s project of contesting essentialised identities – ones that never change. It also downplays his sense of social justice. I wanted to highlight Duiker’s contemplation of psychiatry as an instrument of oppression.

A vacuum called therapy

From the beginning, Tshepo is deeply suspicious of psychiatry’s ability to truly understand his experience. His diagnosis of “cannabis induced psychosis” seems to him a mere tactic of the medical profession to blame their lack of understanding on a substance as ubiquitous as cannabis.

As far as he is concerned, the profession is too arrogant to admit what it does not know. The problem, as he sees it, is not just with specific doctors, but with the way the profession teaches them to see people as data. Tshepo laments that:

When they look at me I know they don’t see a person. They see a case, something that they must work out, decode, diagnose … They listen to what they want to hear and write down what they understand. Everything else, the gestures, the pauses, the looks of despair and desperation disappear in a vacuum called therapy.

Duiker goes on to describe the forms of violence that patients endure in the hospital that render them incapable of functioning at the same capacity they used to. They are electroshocked, drugged, punished and humiliated by cruel nurses until they have learnt to forget who they once were.

Madness

Duiker is hardly the first African novelist to write about madness or psychiatric wards. Novels like Bessie Head’s A Question of Power, Nawal El Saadawi’s The Innocence of the Devil and Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God come to mind. But he is perhaps the first to offer a sustained critique of psychiatry’s mode of understanding as both limiting and oppressive.

His view of madness and decidedly unflattering opinion of psychiatry are resonant with those of thinkers now typically referred to as the anti-psychiatry movement that began from the 1960s.

While in some parts of The Quiet Violence Duiker wonders whether some people are not simply too evil to be let out in the world, he mostly writes of madness as a position that can provide deeper insight to life and solutions to the problems of the world.

This is, of course, an assertion that is best considered with much qualification. It is unlikely that everyone who suffers mental distress will see their condition as something to be preserved or celebrated in the way that Duiker does. And those for whom psychiatric care is out of reach may be more inclined to try it out before making their own judgements.

Why this matters

Nonetheless, Duiker provides a warning against adopting psychiatric knowledge wholesale to the neglect of those indigenous models that may offer more expansive interpretations of what we call madness. For example – and this is a common one – those called to be seers and traditional healers are known to have experiences that mimic episodes of mental distress. It would clearly be unhelpful to diagnose such people with tools that take little or no account of their cultural contexts.

Duiker was a writer with a deep sense of social justice. Although the queer figure seems to have been much dominant in the criticism of his work, a more attentive reading shows that he saw identity positions as both flexible and connected.

In the same vein, he saw different kinds of oppression as intertwined. For him, the society’s treatment of those it declares insane bears much resemblance to the way it treats others who do not conform to its ideal roles. The quest for freedom must therefore be more embracing, be more inclusive of those who are not always the loudest or the most visible in the arenas of political agitation.