In the chaos of Mahikeng’s biggest taxi rank, the distinct voice of a woman announcing the availability of Botswana’s pula stands out. Mmamoreki, as she’s known, sits behind a counter of old fruit boxes. The counter also serves as a front to what is effectively a foreign exchange office that has come to be just as important as a cultural office.

On top of the counter is a variety of products, from sweets to home-wrapped chips. But it is a stack of CDs that draws the most attention. On top of these is Botswana’s legendary traditional music group Machesa’s critically acclaimed sophomore album, Tshipidi (2002). On her less busy days, Mmamoreki spends time explaining the album’s magic and how it dragged a genre out of obscurity.

That it’s still available on streets throughout North West province nearly two decades after its release speaks to its seismic impact. Tshipidi didn’t just change the sound of Setswana traditional music, it shifted the genre, triggering a rebirth driven by working-class entrepreneurial ambition.

Game-changers

Traditional music artists in southern Africa have long relied on informal distribution channels, including selling music in taxi ranks to reach an audience that is often elusive to other genres. For Setswana traditional music artists in North West province and Botswana, while informal channels were critical they were also limiting, often with little value or return for the artist. And in the rare case that an album was stocked by a popular music store or retail chain – a reality exclusive to South African Setswana traditional music artists for years – it was often poorly promoted.

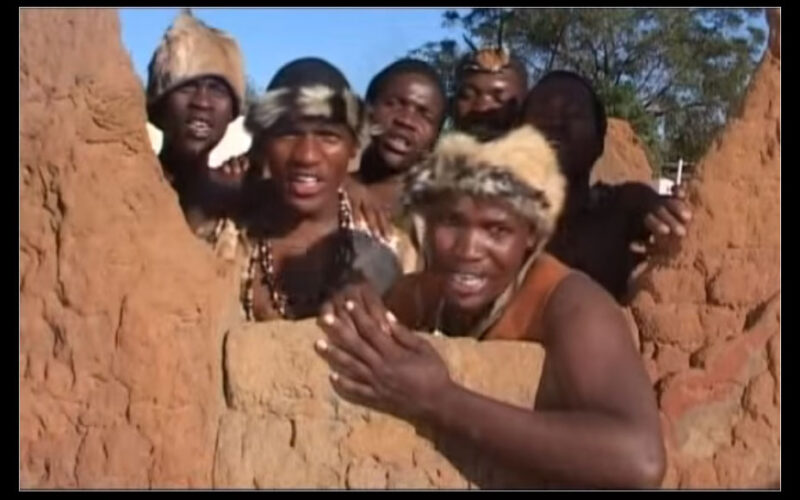

That was until a group of three men wearing Tswana cultural attire began appearing at events and having their music played on the radio. They would call themselves Machesa and their 2001 debut, Moselele, would profoundly shift the genre. Not only did Setswana traditional music sales improve but Machesa also took the genre back where it belonged and was more impactful: the streets.

Phitshane-based trader Classic Rapela was a struggling traditional musician when Machesa came on the scene. He remembers how limited options were for Setswana traditional music artists and the moment Machesa changed this reality.

“When Machesa released Kora, I had all but given up on music. Tradition group performances were limited to weddings and other local events, we didn’t even think selling beyond the province or town was possible. Then suddenly there was a boom driven by these four guys from Botswana, and they had no white masters, they owned their sound. That’s when I decided to sell music,” he explains. “It took off right here at home. Unlike other traditional music genres, we didn’t have to wait for big stations in Gauteng to play our music for us to take ourselves seriously.”

But Machesa’s most important impact was on the music itself.

Shifting sound

For years, South African groups determined the sound of Setswana traditional music, leaving Botswana groups with little choice but to imitate. That sound, however, often seemed self-indulgent and only concerned with preservation – until Machesa arrived on the scene.

Machesa refused to buck the trend of repacking traditional Setswana folk songs and chose to embrace the pen. Writing original songs allowed Machesa to transcend tradition’s limits, the band using their music to probe important cultural values and reckon with their contradictions.

Setswana traditional music groups have long been accused of being backward and of promoting patriarchy. This was one of the reasons for the genre’s long absence from mainstream platforms. But Machesa, a group that was still trying to find its footing when they released their sophomore album, didn’t try to buck that trend, offering a salient critique of patriarchy instead in their Sankarian hit track Sekopa. In it, the protagonist is a recently married woman who is expected to perform all domestic duties while her husband spends most of his time drinking, with lyrics like:

Ngwana Mme wee

Ga wa nyalwa

O latlhilwe

Selo se sag ago

Ke raya ene

Monnanyana wa gagwo

Ke sekopa

Setshoga phekela

Seye sepotong

Se batla dijo

Oh dear my sister

You’re not married

We threw you away

That thing of yours

I mean

your husband

Is lazy

It wakes up early to go drinking

Comes drunk late at night

And wants food

For some of South Africa’s iconic Setswana traditional music groups, such as the Mahikeng-based Maletangwao Cultural Troupe Project, Machesa’s arrival and disregard of the genre’s rules meant a resurgence. Taking a page out of Machesa’s book and marrying their sounds to current issues meant a return to radio for the group. “Radio stations were suddenly responsive to our requests to be playlisted, because of this thing that was happening in Botswana,” explains former dancer Mmamanyane Leleki.

But Machesa’s impact resulted in another shift in the genre. It was only possible because nearly a decade before the release of their debut album, Motseletsele, Eric “Ramco” Ramogobya was dreaming.

Eric Ramco Records

Ramogobya was a frustrated advertising executive when he quit his job at the Botswana Guardian newspaper in 1995 to start Eric Ramco Records. Setswana traditional music was poorly archived and marketed, and artists were seldom compensated. Ramogobya sought to change this.

Starting a record label that would cater for a genre that was effectively non-existent was risky, if not impossible. But having failed twice before settling at the Botswana Guardian, as a businessman and again as an executive at non-governmental organisation Motswana Woman, Ramogobya knew what was at stake.

From 1995 to the early 2000s, Eric Ramco Records would be home to a plethora of artists, including Setswana folk singer Malefo ‘Stampore’ Mokha. It mostly relied on Radio Botswana (RB) and Bophuthatswana Radio (BOP) tapes, which were once the custodians of Setswana traditional music, though with little success or impact.

It wasn’t until 2001, when Ramogobya gathered a group of working-class men – Dimane Lesetedi, Lebitso Galemmone and Samuel Jack – to form the legendary Machesa, that his vision became vivid. By starting a label with a focus on Setswana traditional music and marketing to a broader audience, Ramogobya had already changed Setswana traditional music. But Machesa allowed him to do something that had been almost impossible to achieve: take Setswana traditional music global.

Moselele

When Machesa released Moselele, Ramogobya and the group knew that whether they received acclaim or not, they were on the path to ensuring that Setswana traditional music would never be the same again. But Ramogobya had spent years preparing for this moment.

Moselele sounded like a typical traditional music album in that it was largely a modern interpretation of Tswana folklore. But released to a bigger audience and through more modern distribution channels, it signalled a major arrival of Setswana traditional music. Until that moment, maskandi, which became the voice of migrant workers in South Africa, was the most popular traditional music genre in southern Africa. The arrival of Machesa challenged maskandi dominance and compelled international audiences to broaden their understanding of southern Africa’s indigenous music traditions.

Was Moselele a safe play, as some critics have said? If you judge the album by sound alone then, yes, it was Eric Ramco Records’ safest project. But this answer shifts if you consider its reception and impact. It would become the album that catapulted Setswana traditional music to international stardom, earning Machesa their first two Kora All Africa Music Awards nominations. And while the album’s commercial performance was modest, it carried critical lessons for Ramogobya and the band, lessons they would apply faithfully on their second album.

Taking up the pen

There’s a popular story people tell when asked how Ramogobya was able to do what he did with Machesa’s second album, titled Tshipidi.

It is said Ramogobya walked into the studio when the group was recording and declared that their days of listening to old tapes and remaking old Setswana folk songs were over. The pen was declared mightier than memory. Machesa would reach for it and by doing so, set a new standard.

Tshipidi was a departure from the lyrical caution of Moselele, and allowed Ramogobya and the group to be more adventurous. Critics cautioned Ramogobya that listeners were not ready to hear their precious Setswana being upended, but Ramogobya and the group forged ahead. It did not take long until they were vindicated.

In 2003, the group won the coveted best traditional group award at the Koras. By this time, Setswana traditional music was a regular feature on radio and television. Ramogobya’s dream had been realised. But if Tshipidi crowned Machesa and Ramogobya the kings of Setswana traditional music, then their third album, Kora, announced them as philosophers. They were not only concerned with singing storytelling, they also wanted to reckon with societal issues.

Questioning society and merging belief systems

Kora was an appreciation and a protest album. Having stormed their way to victory by discarding the roles of traditional music, Machesa now set their sights on questioning society. Relying heavily on their songwriting, it was inevitable that the group would clash with the very same society that had made them.

The first shot in that clash was Machesa’s controversial hit song Sango,in which lead singer Lesetedi raises several issues using explicit language. Though they had won hearts with previous albums by choosing to avoid controversial issues, with Kora the group felt emboldened to raise issues, including classism. But Machesa were praised just as much as they were offended.

They merged genres and belief systems, too. There was a general belief that themes of magic and witchcraft sometimes found in traditional music could never be reconciled with the longing for the heavenly ascendance of Christian music. Machesa and Ramogobya begged to differ. Their rebuttal was Jeso Morena, a four-minute appreciation sermon carried on an emphatic traditional music beat.

With this, they proved that the belief that traditional and gospel music can blend was a false dichotomy. Until Kora, no other Setswana traditional music group had tried to balance the sensibilities of African spirituality and tradition with those of Christianity.

Matsieng and the decline

A slew of influential Setswana traditional music artists rose in the wake of Machesa, from Culture Spears to Shumba Ratshega. For a time it seemed as though the genre was poised to challenge popular genres such as gospel and hip-hop, but then it all went south.

No one can really explain what happened to Setswana traditional music, but the most common answer fans give is that the music began to sound the same, imitation replaced creativity. This isn’t an accusation you can level at Ramogobya. He might be accused of many things, but not emulation.

When his work with Machesa lost its rhythm and the band left the label, Ramogobya gathered Liki Tselabem, Kgwasimo (now Morwa Tsankana) and Ditiro “DT” Leero and formed Matsieng. Leero was subsequently convicted, in 2012, of raping a 14-year-old girl.

For the label, Matsieng was an answer to the question of whether or not Eric Ramco would be a one-hit-wonder. And could more be done with Setswana traditional music? Like Machesa, Matsieng quickly garnered acclaim, particularly for their writing. But even the group’s vocal prowess and songwriting could not re-enliven Setswana traditional music.

Now, Ramogobya is back in the studio recording with the group, although without founding member Leero in the line-up. But two decades since he resolved to put Setswana traditional music in its rightful place, the question Ramogobya dreads has returned: Can he popularise Setswana traditional music again? Whatever he creates now will always stand in the long shadow of the seismic impact of his work with Machesa.