Unable to return to South Africa this winter, the dancer and choreographer created a dance piece for film, proving the power of creative expression and collaboration.

UFRIEDA HO

It’s raining in Vichy – five soggy, grey days and counting. This is Vincent Mantsoe’s French home nowadays. His thoughts, though, drift to his other home, to Soweto in winter, when the light cuts like a blade through the bluest of days.

The dancer and choreographer was meant to be back in South Africa this April for a month-long tour, presenting his solo piece SoliiDaD and facilitating a workshop programme. Then the coronavirus slammed into his plans.

“I know those South African skies well. Every year I come home maybe once or twice if I’m lucky. I have to re-energise my body with African soil,” he says, speaking via WhatsApp call.

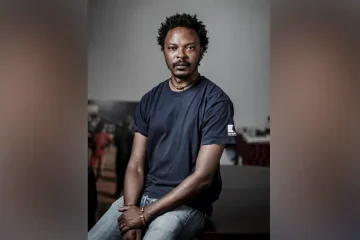

Mantsoe, who turns 50 next year, is celebrated in South Africa and globally. Since joining the company Moving Into Dance in the early 1990s he’s become a formidable figure in dance, first in South Africa then building a career that’s seen him achieve high acclaim around the world. He settled in France 16 years ago after meeting and marrying fellow dancer Cécile Maubert. The couple has two children.

“Lockdown has been interesting, but also a difficult time, especially in France where so many have died. At times my spirit was getting broken; I was here alone in my studio, even with family in the house. I had to stop and start again in the middle of dancing.”

He explains he had to find extra impetus to keep going.

“After my tour was cancelled, the French Institute of South Africa (IFAS) approached me to put together a dance piece for film. At first I wasn’t sure because I have never created a performance for film. I knew though that I wanted to perform something different – not the piece I prepared for the tour,” says Mantsoe.

Creating Cut

Cut is a creation born from the Covid-19 lockdown. There are themes of isolation and confinement, of being cut off from each other because of travel bans, of standing in lines in supermarket queues or feeling disconnected as smiles have vanished behind masks, high walls or been relegated to two-dimensions on computer screens. The world outside our front doors is far away – and our interior lives are perhaps as distant.

Mantsoe produced the powerful 15-minute film in collaboration with Lesotho-based musician and composer Mpho Molikeng and French filmmaker Frank Pizon. It went live on 18 June 2020 through the Facebook pages of IFAS and the Market Theatre, the producers of the film, and is available for free viewing for two weeks.

“At first I was really not sure about film because my work doesn’t speak to the camera. It speaks to the public, face to face. The audience feels something in the moment and travels with me as the performer in the moment. So this was something very new.

“I was also cut off from Frank and from Mpho, and we had to find a way to collaborate without being in the same room, and it wasn’t easy,” says Mantsoe. The piece is filmed entirely in Mantsoe’s studio. Mantsoe is in dance sweats – there isn’t lighting, a stage or props.

The viewer, though, gets a glimpse of his personal work space. It’s sparse and utilitarian except for two instruments, an umrhubhe and an uhadi that hang from a wall. They are from a previous work of his called Men-Jaro. They are also touchstones from the continent of his birth that he hasn’t been able to reconnect with this winter.

Mantsoe set up two cameras to film himself for Cut and kept recording from different angles as Pizon directed.

Sonic inspiration

It was a similar remote process with Molikeng. Mantsoe sent samples of music he thought would work best and then, back and forth, recordings were sent with new inputs till the music matched what Mantsoe had in mind.

Molikeng eventually created seven pieces of music from which Mantsoe chose the composition that was just right.

Speaking from Maseru, Molikeng says he drew inspiration from sounds from the natural world. There are also the sounds of the body – screams, gasping and thumping footsteps. He’s also added signature traditional instruments, including the lesiba, bells and horns.

“I had to watch a lot of Vincent’s previous performances and try to understand his head space musically and what would work for the way he moves his body.

“The music is traditional but also contemporary, and I recorded it from instruments being played live so you can almost hear the hands, the mouth and the breathing. I wanted natural sounds and the sounds of our concrete jungle because in lockdown, we are wanting natural sounds because all our sounds now are from the TV, the internet and everything that is industrial,” says Molikeng.

A shift in filming

For Pizon, not being in the room for filming took a massive mind shift. He says: “The power of Vincent’s dance requires precise filming and I had to propose to him to arrange the cameras on his own. It was interesting because he was sometimes very close to the camera and sometimes far away, but those two perspectives allowed me to restore the power of his artistic expression.”

Pizon chose to make the film black and white, and his edits are striking parallels to the tempo of the dance.

Sometimes there are physical black boxes that cut Mantsoe out of the screen. Sometimes he seems to be nudging them away. The frames clip and flash at times, playing off the haunting pulsations in Molikeng’s music and Mantsoe’s movements and gestures. There are montages with black frames reducing or enlarging. Pizon says he used this technique as a metaphor for the “walls of a room that lock you in or out”.

He adds: “Black and white restores the strength of these very special moments. It is outside of time. With containment, time passes differently. The shades of grey reflect better the whole range of emotions that we could feel.

“I realised that I was reading Vincent’s emotions like an open book. All I had to do was to immerse myself in this performance,” Pizon adds.

The pull of performance

Now it’s over to viewers to immerse themselves in the film the team has created. Mantsoe admits he fears the silence and passivity of a viewer clicking on a link and giving a thumbs up, rather than rising in applause and being part of the ritual and throb of a live performance.

But there’s vigour and life in Cut. Mantsoe comes from a family of sangomas, he says. It is a heritage reflected in how he explores the tenuousness of things passing, of transformation and transitions, of disruption, anxiety and the churn of emotion as the world reconfigures through Covid-19. He pulls you in from the opening frames when a bead of sweat falls from his face. He sweeps you along on a journey to the moment his hands are in his mouth searching for breath, clawing for it. Then, in the concluding seconds of the film, his body ripples in tremors and shakes – a fight for life, maybe, is also the moment he exits the final frame.

It’s raining in Vichy – five soggy, grey days and counting. This is Vincent Mantsoe’s French home nowadays. His thoughts, though, drift to his other home, to Soweto in winter, when the light cuts like a blade through the bluest of days.

The dancer and choreographer was meant to be back in South Africa this April for a month-long tour, presenting his solo piece SoliiDaD and facilitating a workshop programme. Then the coronavirus slammed into his plans.

“I know those South African skies well. Every year I come home maybe once or twice if I’m lucky. I have to re-energise my body with African soil,” he says, speaking via WhatsApp call.

Mantsoe, who turns 50 next year, is celebrated in South Africa and globally. Since joining the company Moving Into Dance in the early 1990s he’s become a formidable figure in dance, first in South Africa then building a career that’s seen him achieve high acclaim around the world. He settled in France 16 years ago after meeting and marrying fellow dancer Cécile Maubert. The couple has two children.

“Lockdown has been interesting, but also a difficult time, especially in France where so many have died. At times my spirit was getting broken; I was here alone in my studio, even with family in the house. I had to stop and start again in the middle of dancing.”

He explains he had to find extra impetus to keep going.

“After my tour was cancelled, the French Institute of South Africa (IFAS) approached me to put together a dance piece for film. At first I wasn’t sure because I have never created a performance for film. I knew though that I wanted to perform something different – not the piece I prepared for the tour,” says Mantsoe.

Creating Cut

Cut is a creation born from the Covid-19 lockdown. There are themes of isolation and confinement, of being cut off from each other because of travel bans, of standing in lines in supermarket queues or feeling disconnected as smiles have vanished behind masks, high walls or been relegated to two-dimensions on computer screens. The world outside our front doors is far away – and our interior lives are perhaps as distant.

Mantsoe produced the powerful 15-minute film in collaboration with Lesotho-based musician and composer Mpho Molikeng and French filmmaker Frank Pizon. It went live on 18 June 2020 through the Facebook pages of IFAS and the Market Theatre, the producers of the film, and is available for free viewing for two weeks.

“At first I was really not sure about film because my work doesn’t speak to the camera. It speaks to the public, face to face. The audience feels something in the moment and travels with me as the performer in the moment. So this was something very new.

“I was also cut off from Frank and from Mpho, and we had to find a way to collaborate without being in the same room, and it wasn’t easy,” says Mantsoe. The piece is filmed entirely in Mantsoe’s studio. Mantsoe is in dance sweats – there isn’t lighting, a stage or props.

The viewer, though, gets a glimpse of his personal work space. It’s sparse and utilitarian except for two instruments, an umrhubhe and an uhadi that hang from a wall. They are from a previous work of his called Men-Jaro. They are also touchstones from the continent of his birth that he hasn’t been able to reconnect with this winter.

Mantsoe set up two cameras to film himself for Cut and kept recording from different angles as Pizon directed.

Sonic inspiration

It was a similar remote process with Molikeng. Mantsoe sent samples of music he thought would work best and then, back and forth, recordings were sent with new inputs till the music matched what Mantsoe had in mind.

Molikeng eventually created seven pieces of music from which Mantsoe chose the composition that was just right.

Speaking from Maseru, Molikeng says he drew inspiration from sounds from the natural world. There are also the sounds of the body – screams, gasping and thumping footsteps. He’s also added signature traditional instruments, including the lesiba, bells and horns.

“I had to watch a lot of Vincent’s previous performances and try to understand his head space musically and what would work for the way he moves his body.

“The music is traditional but also contemporary, and I recorded it from instruments being played live so you can almost hear the hands, the mouth and the breathing. I wanted natural sounds and the sounds of our concrete jungle because in lockdown, we are wanting natural sounds because all our sounds now are from the TV, the internet and everything that is industrial,” says Molikeng.

A shift in filming

For Pizon, not being in the room for filming took a massive mind shift. He says: “The power of Vincent’s dance requires precise filming and I had to propose to him to arrange the cameras on his own. It was interesting because he was sometimes very close to the camera and sometimes far away, but those two perspectives allowed me to restore the power of his artistic expression.”

Pizon chose to make the film black and white, and his edits are striking parallels to the tempo of the dance.

Sometimes there are physical black boxes that cut Mantsoe out of the screen. Sometimes he seems to be nudging them away. The frames clip and flash at times, playing off the haunting pulsations in Molikeng’s music and Mantsoe’s movements and gestures. There are montages with black frames reducing or enlarging. Pizon says he used this technique as a metaphor for the “walls of a room that lock you in or out”.

He adds: “Black and white restores the strength of these very special moments. It is outside of time. With containment, time passes differently. The shades of grey reflect better the whole range of emotions that we could feel.

“I realised that I was reading Vincent’s emotions like an open book. All I had to do was to immerse myself in this performance,” Pizon adds.

The pull of performance

Now it’s over to viewers to immerse themselves in the film the team has created. Mantsoe admits he fears the silence and passivity of a viewer clicking on a link and giving a thumbs up, rather than rising in applause and being part of the ritual and throb of a live performance.

But there’s vigour and life in Cut. Mantsoe comes from a family of sangomas, he says. It is a heritage reflected in how he explores the tenuousness of things passing, of transformation and transitions, of disruption, anxiety and the churn of emotion as the world reconfigures through Covid-19. He pulls you in from the opening frames when a bead of sweat falls from his face. He sweeps you along on a journey to the moment his hands are in his mouth searching for breath, clawing for it. Then, in the concluding seconds of the film, his body ripples in tremors and shakes – a fight for life, maybe, is also the moment he exits the final frame.