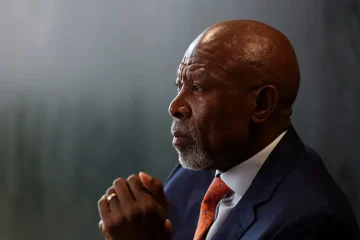

DJAFFAR AL KATANTY

PERCHED on a super-sized tricycle laden with sacks of mangoes, disabled courier Claude Kalwira scooted over the short stretch of no-man’s-land between Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Due to his disability, Kalwira has a permit to shuttle some goods in and out of Congo tax-free, but an eight-month border closure last year caused by the coronavirus meant he and 200 fellow couriers saw business dry up.

While borders reopened on November 5, a new testing requirement means the 30-year-old’s cart, a hodgepodge of steel tubing and butchered motorcycle parts, is now one of only a few dozen plying the route between the twin cities of Rubavu and Goma.

“This border is vital for us,” said Kalwira, who lost his right arm in a car accident when he was young.

In a country with few opportunities for people living with disabilities, Kalwira’s trade exists thanks to a decades-old quirk in customs law.

Sending goods via the custom-made carts is cheaper than hiring a truck, so demand bounced back once travel resumed across the busy crossing.

But most have not been able to benefit.

The authorities now require the couriers to take regular COVID-19 tests, which at $40 per swab is a prohibitive cost for many who earn less than $20 per day.

Rwanda gives free tests to Kalwira and around 60 of his colleagues, but the remaining 140 couriers must pay their own way.

Hoping for a break, the out-of-work couriers have been gathering on their hybrid bikes on the Congolese side of the border.

Father-of-six Dieu Merci Kahasha called on the Congolese government to step in.

“If Rwanda can help the Congolese people by giving them free tests, our government should also … so that we too can find food for our families.”