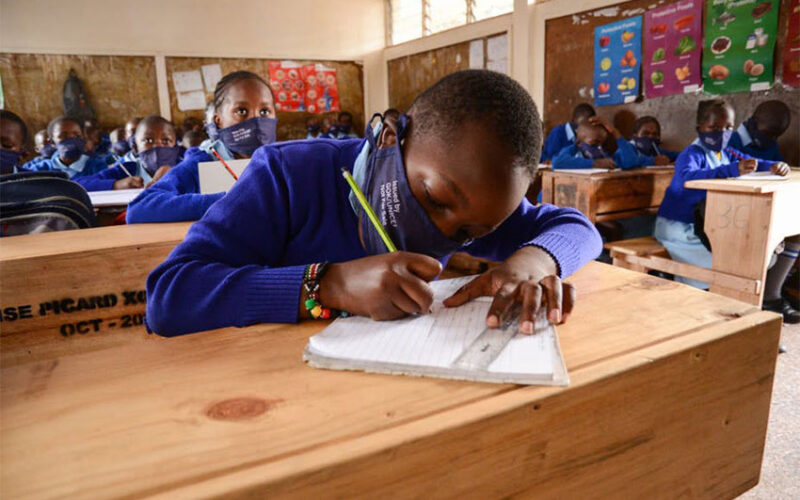

ONE of the sectors that the COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted massively is education.

The COVID-19 pandemic has widened gaps between countries, systems, institutions and learners. The divide has become more pronounced when it comes to wealthy vs poor; private vs state; technology proficient vs technology deficient; academically inclined and predisposed vs academically fragile and in need of support.

In a recent paper, we argue that, as is often the case with major societal disruptions, the pandemic has forced educators to firefight immediate challenges. Around the world, schools and universities are concentrating on the bare minimum: keep learning going and keep students in class. They also have to ensure basic assessment and course continuation. Just “getting through” has been difficult enough without entertaining the deeper philosophical aims of learning.

But the widening gaps between students carry ominous warning signs. Studies show that access to education is the cornerstone of socioeconomic and social growth. When education suffers, many other dimensions of society suffer.

It has become more important than ever to recalibrate and refocus on the big picture of asking: what is an education for?

This is the big question that keeps coming back to those involved in curriculum design, teaching and learning. On the ground – across contexts and systems – education is typically focused on knowledge regurgitation and the practice of academic skills. This is based on grade averages and examination scores, which eventually lead to higher education.

While we recognise the value of standardised testing and quantifiable learning outcomes, this is a narrow conception of learning. It does not allow all learners to realise their full potential.

In an age of rapid change and the need to nurture competences, it is necessary to design systems that allow students to flourish and not just focus on graded academic subjects.

We argue that learning is a social, intellectual and physical enterprise. It comprises many different facets of human growth. Students learn much outside of school and outside the narrow confines of an academic curriculum. Curricula and certification need to reflect this broader, more inclusive worldview. This needs to be done by building competence-based programmes and reforming high school transcripts.

Rethinking the purpose of education

The fundamental purpose of education is to improve the human condition. The idea is that education should lead to a longer and better life, a higher income, and a better society. In the 21st century, these goals need to include questions of planetary sustainability and social justice.

Learning objectives should not only be focused on knowledge or the dry technicality of skills, but a combination of knowledge, skill and disposition (meaning attitude): what we call a competence.

For UNESCO’s International Bureau of Education, a global competence is:

the developmental capacity to interactively mobilise and ethically use information, data, knowledge, skills, values, attitudes, and technology to engage effectively and act across diverse 21st century contexts to attain individual, collective, and global good.

Seven core areas UNESCO’s International Bureau of Education suggests educators develop in every student are:

- Lifelong learning (persistence, curiosity and the ongoing desire to learn)

- Self Agency (autonomy, independent thinking and accountability)

- Interaction with others

- Interaction with the world

- Interaction with diverse tools and resources

- Transdisciplinarity (making connections across disciplines)

- Literacy across many different areas and subjects

UNESCO’s competences framework, and other initiatives, attempt to break curriculum conservatism to bring about more dynamic approaches. The focus is on the skills, knowledge and attitudes that are needed for global citizenry in a complex world.

Competences for global citizenship should emphasise life-worthiness. This means skills that can be used in everyday life. They should also emphasise wellness and the development of a moral conscience and the courage to act for engaged citizenry. An example of a programme that does this is the International School of Geneva’s Universal Learning Programme.

More and more higher education systems are embracing competence-based models. Many of which are similar to the Universal Learning Programme and the UNESCO International Bureau of Education’s approach.

A competence-based approach will allow children in under-resourced environments to show their worth in different ways to academic testing, which, as much research has shown, gives a clear advantage to wealthier children.

However, across education systems, there is still a long way to go to have a curriculum that is truly life-worthy, relevant and that allows students to connect what they do at school with local and global issues.

COVID-19 has highlighted the weaknesses of education systems to resist major disruption. The pandemic has shown how large-scale assessment design falls apart. It becomes difficult to piece together a student’s profile for university admissions without resorting to non-optimal proxies, such as predicted grades.

End of school certification needs musn’t solely focus on grades or single instances of data capture, like high-stakes timed examinations. It needs to be a more sustainable and reliable narrative.

A new transcript

Perhaps the most essential element of the educational pathway to reform is the end of school transcript. Schools, universities and industry need to work together to reform this narrow, grade-centered approach into something more inclusive. This, in turn will not only open more access to a broader base of students but will align more coherently forward-looking curriculum reform with pre-tertiary entrance criteria.

We hope and expect to see a coalition of schools and universities produce this reform in the very near future.