JAN BORNMAN

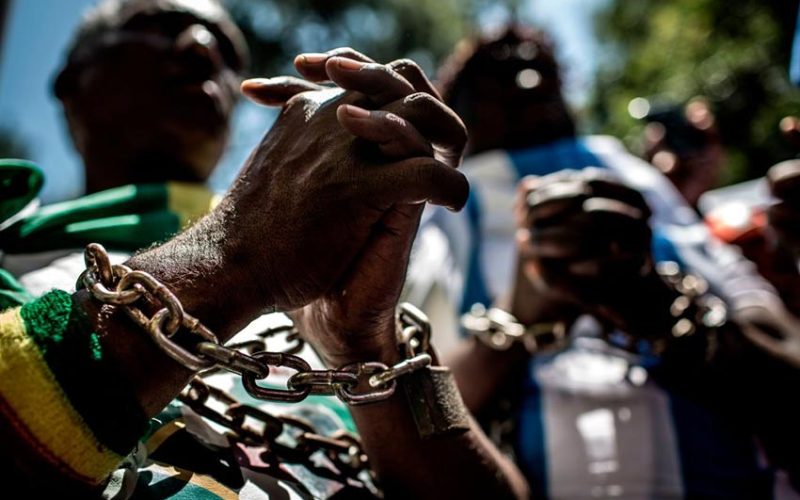

HUMAN trafficking is a topic that never seems far from the public imagination. Regular awareness campaigns ensure it is always included in conversations on fighting crime, and in South Africa, barely a day goes by without someone posting about it on social media.

More often than not, though, people tend to link human trafficking to sex trafficking and, invariably, sex work. But globally and in South Africa, experts have warned that sex work is often conflated with human trafficking and the voices and experiences of sex workers are thus dismissed or excluded.

In a 2020 research report by the Centre for Child Law at the University of Pretoria, titled Child Trafficking in South Africa: Exploring the Myths and Realities, the researchers emphasise how the lack of clarity in defining it means the term “trafficking” can be used in many different ways and “to define many, very different things”.

The report finds “For those with a primary focus on controlling and restricting immigration, a distinction can be made between ‘deserving’ migrants (i.e. victims of trafficking seen as lacking agency) and ‘criminal’ migrants (i.e. those who show agency and made choices in the process of moving).

“Meanwhile, for those focused on migration within a human rights framework, the definition of trafficking could be extended to include all those who end up in forced labour and ‘slavery-like conditions’. The vagueness of the definition also allows for the conflation of sex work with trafficking and enables those who object to sex work to frame all migration into the sex work industry as ‘trafficking’ regardless of whether or not a choice was made.”

The experiences of Zoe Black* show why sex work and human trafficking are more complex issues than they are made out to be. Black, 37, is an undocumented migrant from Zimbabwe who came to South Africa more than a decade ago after separating from her husband and falling on tough times. But prior to her arrival, and with no previous experience of sex work, she turned to it when money started running out and she became desperate.

“So that was my first time when I had to go to a hotel, a five-star hotel… I only had enough money for one beer. I sipped on this beer the whole night, and this guy walked in and I started talking to him. The rest is history. I made enough money to pay school fees for my kids. It was less than an hour,” she explained.

Smuggled by choice

After a while, Black decided to come and work in South Africa, entering the country with a valid passport and leaving her four children behind with her mother. When her passport expired, she wanted to renew it in Zimbabwe and then re-enter South Africa legally, but at the border post she was banned from returning for overstaying her visa.

Unable to get herself unbanned and desperate to get back to South Africa where she was making more money in sex work, Black opted to use a “smuggler” to help her return, using money her partner had sent her. “It’s like going to the toilet and coming back,” she said of how easy it was to do it.

“So I got a bus in Harare and I told the driver I didn’t have a passport and he said it’s fine. This is the money I am paying for the bus, and he said since I don’t have a passport I have to pay extra. Then I got on board, I paid the money. We get to the border and everybody stays together. We don’t do anything,” Black explained.

“We go through all the processes with everybody else… When you don’t have money, you walk across the river where there are crocodiles. But when you have money, then you come through the border. It’s that simple – it is happening every day,” she said with a laugh.

“Their [the smugglers’] policy is ‘we don’t leave anyone behind’. You’re basically guaranteed a safe passage, whichever way, even if you don’t have papers. They will make sure you get across the border.”

Black has since gone back to Zimbabwe using this method of smuggling and returned to South Africa again. Hers is an experience that is more common than most people would imagine, she says. Despite her own agency in wanting to make the journey to South Africa to do sex work, the definition of human trafficking used in the country’s legislation could potentially view her as a victim of human trafficking.

Fake and dangerous

Researchers and experts say misrepresenting all sex work as consequent to human trafficking can legitimise state violence and result in forced deportations. There are a lot of awareness campaigns, messaging and fake reports about human trafficking in South Africa that endanger the lives of people such as Black.

As she said: “For me, trafficking stats and that, it doesn’t reflect what’s going on. There’s no real evidence that it’s as bad as people say. But in theory, personally, I think it happens but it’s not known or spoken about because they cannot find it. It is a very closed network.

“At the end of the day, trafficking stats, I think, are overinflated and the same way you don’t know, I don’t know… But I think it’s just the notion that if someone leaves somewhere, they were forced to leave… So this notion that sex workers don’t have an interest in trafficking and that they are victims is wrong,” she said.

Black adds that sex workers should be included in the fight against human trafficking because they are often the first to identify trafficking victims on the streets and can alert the authorities.

The extent of fake news around human trafficking in South Africa is such that the police had to issue at least two statements in September last year warning the public about spreading rumours and fake news about it. “Even though human trafficking is not [as] prevalent in South Africa as it is in other parts of the world, we must adopt a collective approach ensuring that not a single person, man, woman or child, becomes a victim of this crime,” national police spokesperson Brigadier Vishnu Naidoo said in one statement.

The most recent Trafficking in Persons report of the United States Department of State has upgraded South Africa to its tier two watchlist, stating that human traffickers exploit domestic and foreign victims. Despite the report being used as a global measurement and comparative tool, some researchers have raised questions about it as well as other efforts to measure the prevalence of exploitation and human trafficking.

Sport and sex

Reports and awareness campaigns about human trafficking to exploit young girls and women for the sex trade also seem to increase with every major sporting event. Claims about human trafficking, including trafficking in children, became increasingly exaggerated in the build-up to the 2010 Fifa World Cup in South Africa, while the Super Bowl final in the US in February saw a renewed focus on anti-trafficking campaigns.

In a 2019 article in the Anti-Trafficking Review, an open-access and peer-reviewed journal dedicated to a human rights approach to anti-trafficking research, researchers Lauren Martin and Annie Hill debunk myths around sex trafficking at the Super Bowl. They found no increases in trafficking for sexual exploitation ahead of, or during, major sporting events like World Cups and Olympic Games.

“Anti-trafficking efforts spurred by sporting events tend to focus on addressing ‘sex trafficking’, rather than trafficking for labour exploitation. This emphasis holds true for anti-trafficking campaigns more generally,” Martin and Hill write.

They say there are more reasons to investigate labour exploitation in relation to major sporting events and cite the horrific track record of migrant construction workers’ experiences in Qatar ahead of the 2022 World Cup. This is supported by a recent report in The Guardian which found that 6 500 migrant workers from India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka have died in Qatar since the country won the bid to host the World Cup.

“Recent research highlights trafficking, extreme abuse and the death of workers connected to Russia’s 2014 Winter Olympics and Qatar’s preparations for the 2022 World Cup. However, the media and anti-trafficking stakeholders often neglect these victims and forms of violence in favour of a focus on trafficking for sexual exploitation,” Martin and Hill write in the Anti-Trafficking Review.

Following the Super Bowl final, there were reports in the US media about a record number of people arrested in a “human trafficking” sting, with the police stating that 75 people had been arrested after “trying to buy or sell sex”. Martin and Hill warn about the dangers of conflating terms and inflating numbers in discussions on human trafficking for sexual exploitation. “Terminological conflation was common to how sources, generally perceived by the public as authoritative, framed trafficking and anti-trafficking efforts,” they write.

Separating the issues

The conflation of human trafficking for sexual exploitation with sex work is not just a phenomenon associated with major sporting events, but happens in daily conversations about the two topics. Sex worker rights and advocacy organisations in South Africa say they are routinely excluded from discussions about human trafficking and sex work.

Many progressive researchers around the world have written about the positive impact that the decriminalisation of sex work would have on the safety of sex workers, and it has been backed up by organisations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International.

There is a stark ideological divide among researchers in the human trafficking and trafficking for sexual exploitation space. Marcel van der Watt, a former investigator in the police’s Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation and a human trafficking researcher says those on the one side of the ideological divide largely dismiss the prevalence of human trafficking in the sex trade while advocating for the full decriminalisation of sex work in South Africa.

He says researchers misconstrue the definition of “trafficking in persons” and omit the “abuse of vulnerability” as defined by the Prevention and Combating of Trafficking in Persons Act that was signed into law in 2013.

“The first thing you have to realise is that trafficking and voluntary sex work cannot be conflated as they have different legal definitions, both in South Africa and elsewhere in the world. My criticism comes in when these phenomena are conveniently and clinically separated when rosy narratives about the sex trade is crafted in furtherance of full decriminalisation,” he said.

Van der Watt and four other researchers argued last year that support for the decriminalisation of sex work and non-securitisation of migration was firmly rooted in the sceptical view about human trafficking.

Martin Ewi, a senior researcher at the Institute for Security Studies, says the law was designed so broadly to ensure there were no loopholes. “Of course the law has its weaknesses,” he said. “We saw how it has affected immigration. It has affected a lot of other industries. It has affected how we travel with children. That is why you hear about a lot of complaints about the law. [But] everything was done in order to prevent human trafficking.

“That’s the challenge we face in the law. There’s the misunderstanding, and the nature of the law was extremely broad and it was linked to immigration and many other things in order to close any potential loopholes that traffickers can use.”

Sex work vs exploitation

South African researchers Ntokozo Yingwana, Rebecca Walker and Alex Etchart have developed a model to distinguish between migrant sex work and trafficking. They warn that conflating the two issues not only distracts from a sector such as labour where trafficking is prevalent, but that it provides ammunition for the anti-sex work and anti-immigration lobbies to carry out their own agendas.

The model defines and distinguishes sex work, exploitation and migration, and argues it should only be considered trafficking for sexual exploitation when the three intersect. Yingwana, Walker and Etchart also warn that sex workers, particularly migrant sex workers, are vulnerable to a variety of human rights abuses during “raid and rescue operations” and that these operations often lead to their deportation, rendering them unable to earn an income and access social services.

Nosipho Vidima, a sex worker and the sex worker rights project specialist at non-profit organisation Sonke Gender Justice, says it is harmful to sex workers and their safety to view them without agency when conflating issues of sex work and human trafficking with the intention of sexual exploitation.

“I would really like our government, when dealing with sex work or the sex industry and trafficking in the sex industry and migration, to start applying that model [so that] even the state officials who are dealing with matters or doing the investigations use it and understand it,” she said.

Vidima says there are insufficient data on trafficking for sexual exploitation in South Africa to justify the resources spent on advocacy campaigns that focus on it. “Somebody is either blowing up the sex trafficking numbers when they go to the media, or there is just under-reporting everywhere,” she said.

Instead, Vidima says, more attention needs to be focused on human trafficking for other forms of exploitation such as labour.

*Not her real name

This story is part of a continuing project on human trafficking in collaboration with Code for Africa and with support from the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit.