[tta_listen_btn listen_text=”Audio” pause_text=”Pause” resume_text=”Resume” replay_text=”Replay”]

ON a cool, moonlit night in 1966, as the people of Kom lay sleeping, a significant cultural symbol disappeared from under their noses.

Located in the western grasslands, Kom, formerly an independent kingdom, became an administrative division in Cameroon when the country gained independence in 1960.

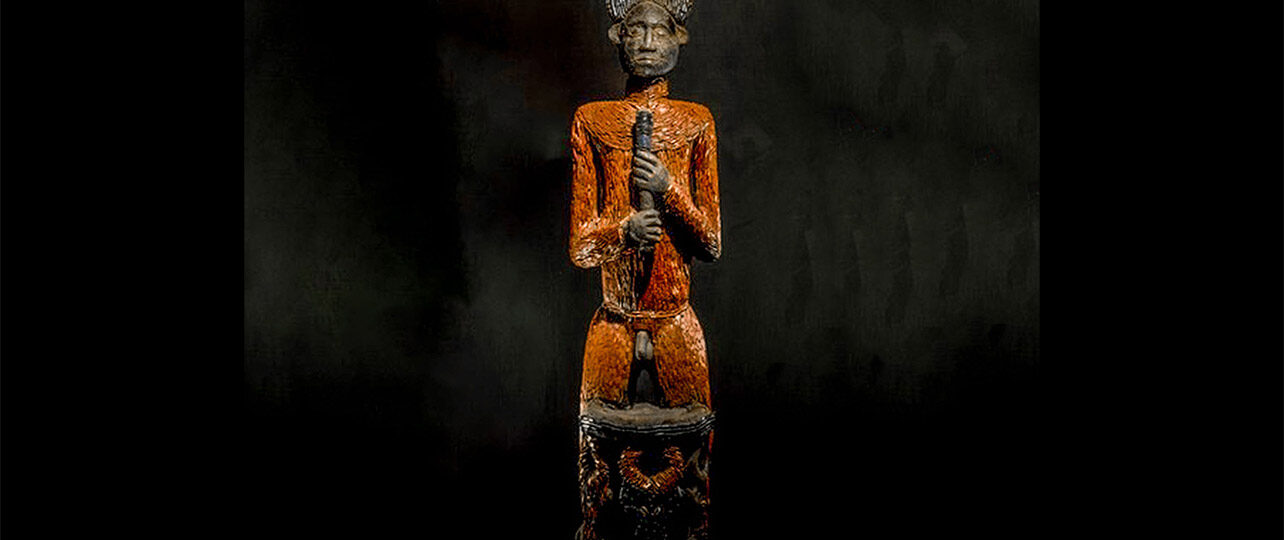

The most revered symbol of the Kom people is a 159-centimetre carved wooden statue. It depicts a man standing behind a small throne, wearing a crown and holding a sceptre.

The wooden sculpture, called Afo Akom (which translates as the “thing of Kom”), was kept in storage at the king’s palace. It was only displayed once a year, during an annual ceremony. When exhibited, it could not be approached; people could only admire it from a distance.

A ceremonial guard at the palace watched over the hut’s entrance around the clock. But that night in 1966, the guard’s legs hurt, and he needed a break. He left his young assistants in charge while he was away.

Early in the morning, the Kom community of 80,000 people received the distressing news that their precious sculpture had been stolen during the night. Further investigations showed that the sculpture had been smuggled out of Cameroon via the Douala international airport.

To placate his people, the traditional monarch ordered a replica of the statue. However, the public disapproved and insisted on having the original instead of a duplicate. Without their beloved Kom, the community mourned.

Then, seven years later, the statue unexpectedly resurfaced.

In 1973, Dartmouth College, a prestigious university in the United States, hosted an exhibition of artefacts. A scholar from Kom who happened to be living in the US attended the exhibition. Among the numerous pieces on display, his eye was drawn to a particular object. Upon closer inspection, he identified the Afo Akom, the sacred sculpture his community had been grieving, for the past seven years.

The object was on loan at Dartmouth College from the Furman Gallery in Manhatten, in New York. The gallery was operated by art dealer Aaron Furman.

Through their embassy in the US, the Cameroonian government officially demanded the restitution of the object and initiated a diplomatic process with the US administration.

The American press took up the case. The New York Times, the St. Petersburg Times and Jet magazine followed the story, making the US public aware of the matter.

Despite being approached, Aaron Furman hesitated to return the piece to Cameroon. He claimed that he had acquired the statue legitimately from a reputable dealer outside of Africa who had also sold him other art objects. Furman’s lawyer stated that he acted in good faith and was not inclined to return the statue to the Kom.

Some personalities and organisations, including the Cameroonian embassy and the US administration, lobbied for the restitution. Among them were Warren Robbins, a famous African Art collector and founder of the Museum of African Art at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, and African-American activist and leader of the Black United Front, Douglas Moore.

Yielding to the pressure, Aaron Furman finally consented to return the sculpture after being assured he would be reimbursed the amount he had paid.

In a press conference in 1973, the Cameroonian embassy cultural attaché, Nkuo Taddeus, who happened to be from the Kom community, explained that the Afo-A-Kom was “beyond money, beyond value. It is the heart of the Kom, what unifies the tribe, the spirit of the nation, what holds us together. It is not an object of art for sale, and could not be”.

Brokering the transaction, Warren Robbins collected money from donors to repay the initial fee, while the Afo Akom was displayed at the Museum of African Art in Washington.

The statue was then returned to Cameroon in December 1973, to a triumphal welcome, and was given back to the Kom people.

This is how the Afo Kom acquired its celebrity status, became a national treasure and is recognised as one of Africa’s most important artworks. However, its original purpose was never to be admired as a simple piece of art but to be kept out of everyone’s sight.

Today it is once again kept securely in the Laikom palace in Kom and is still displayed annually in front of the Kom people.