THE year was 2011, Ice Prince had already released his chart-topping song, “Oleku,” featuring industry newcomer Brymo, and plans were underway for a music video. This would be a star-studded affair, featuring appearances by Wizkid as well as M.I. and Jesse Jagz, Ice Prince’s label mates at Chocolate City, a Nigerian record label. But before plans were finalised, the music label received an unusual request.

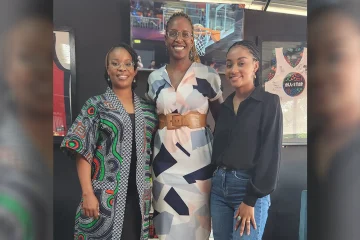

“Even though the Chocolate City crew members were scattered across the world, Ice Prince wanted all of us to be present for a cameo appearance,” said Doosuur Tilley-Gyado, who had assumed dual roles as Talent Manager and General Manager at the record label two years earlier. It was a seminal moment for Tilley-Gyado and an important moment for the music business.

While the six-man crew maintained poker faces for their brief cameo, Tilley-Gyado shared that it was a cherished moment for everyone there, given the amount of time that was spent working behind the scenes.

“It was a form of documentation,” she said.

In her role, the key performance indicators (KPIs) revolved around sales, publicity and bookings, but she embraced additional responsibilities when they came. She vividly recounted hustling to engage marketers at the popular Alaba International Market, a major distribution hub for the Nigerian music and film industry.

“In those days, media campaigns were very much a physical activity and Alaba was ‘the industry,’” she explained.

These marketers were an organised group of traders who ran a large piracy market of CDs. This illicit activity gained momentum in the early 2000s and, ironically, became influential in determining the success of artists. These traders exploited the lack of structure and weak regulations in the industry.

An old Financial Times article on piracy in Nigeria’s creative industry reported that some artists paid to have their songs included in these pirated CDs to generate the hype needed for corporate sponsorship.

“These marketers” owned distribution and the music business is about distribution,” said Tilley-Gyado, at the time baffled that non-music entities could wield such control over the industry.

Regardless, Tilley-Gyado made her mark in the entertainment public relations industry, propelling the artists under her management into the mainstream Nigerian music scene and global recognition. However, the absence of female artists in her portfolio still unsettled her.

Several industry experts have pointed to the financing landscape as a contributing factor to the low representation of female creatives, in addition to the general perception of females as high maintenance. Ibukun “Aibee” Abidoye, the first female executive vice president of Chocolate City, highlighted this in an interview with Teen Vogue.

“When you think about the way record labels were set up, most of them were funded by personal earnings,” she said.

This dynamic, she explained, has led to a preference for male artists because they are viewed as low-risk.

UNESCO’s 2022 publication on the global creative industry reported a critical underrepresentation of women in the film and music industries, with fewer than 10% reported in some African film industries.

Following the signing of Brymo, Chocolate City’s fourth successive male artist, Tilley-Gyado became very agitated.

“I took matters into my own hands and conveyed to the label’s founders that their next signing should be female,” Tilley-Gyado said.

Her speaking up paved the way for female artists like Pryse and Victoria Kimani to come into the limelight.

Providing a solution to this gender gap would further define Tilley-Gyado’s comeback to the entertainment industry after she left Chocolate City in 2013.

“It felt like the right time. Also, Aibee had just come in, and I felt like the company was in good hands,” she said about her decision to leave.

After departing from the music label, she turned her attention to Redbox Ltd., an event planning company she had founded with her assistant in 2012. She followed it up four years later with Small Business Big World, a brand consulting and PR agency. Earlier in 2023, she was appointed as the chief operating officer of the PR firm, So.Me Solutions Group.

“At this company, there’s maybe two men pushing the company; the rest are women,” she said. It is one of Tilley-Gyado’s resolutions to work with more women.

“I want to attract more like-minded women, like myself, to work with,” she said.

This is one way she believes she can support younger creatives – something she believes there is not enough of the male-dominated industry. She noted that the absence of support manifests in multiple ways.

In early 2023, Tilley-Gyado and other female creatives collaborated with the founder of Eden Venture Group, a social enterprise, to launch a campaign called #WEECreateAfrica.

The campaign, a direct response to the gender gap in the industry, got its name from its objectives to foster women’s economic empowerment at the intersection of the creative economy in Africa.

“We believe that there’s a lot of synergies that exist that can help Nigeria and Africa in synergising solutions and creating awareness to essentially end some of the atrocities that women have to suffer,” Fifehan Osinkalu, the founder of the group, said, interview to mark the launch of the campaign.

In addition to generating public awareness, wealth creation is another core aspect of the campaign.

“In my previous role working in private equity and the VC space, I realised that most people, especially in the finance space, did not really understand the language of creatives, or even the language of women,” said Osinkalu in an interview with TechCabal.

Tilley-Gyado explained that improving access to funds for women is crucial to strengthening their capacity at the decision-making level. She envisioned that it would generate broader positive outcomes. She cited the former Nigerian Minister of Women’s Affairs, who invited her and various industry players to contribute to gender-sensitive policies.

“If we have more women up there, then we can easily communicate our needs because they understand our perspective, facilitating the allocation of funds,” she said.

She further advocated for funding in the form of grants over loans.

“Women are already late in the game, so we cannot afford to have loans with potentially crippling interest rates,” she said.

Oluwatoyin Adegbite-Moore, executive vice president for Africa and Europe at EdTech company REACH, aspired to work as an artist but found the challenges for women in the industry too exacting.

“Even though I had a rich voice, I never got the chance for, maybe, a duet,” she said, referring to her time working as a backup singer.

According to Angel Nduka-Nwosu, a versatile creative and founder of The Emecheta Collective, a WhatsApp group for female creators, initiatives like #WEECreateAfrica are vital to address gender-specific challenges in the industry, including protection against sexual predators.

“By having women mentors who offer advice and tips for free, women are challenged to be better creatives without the risk of being exploited by men,” Nduka-Nwosu explained.

Today, Adegbite-Moore’s three children are carving out their paths for themselves in the creative industry.

During the recently concluded Africa Creative Market Conference, Ramin Toloui, the Assistant Secretary for US Economic and Business Affairs, projected that the Nigerian creative industry could generate $100 billion by 2030.

“If we harness the entire value chain of the creative industry, then $100 billion is a conservative estimate. Women play a pivotal role in this value chain,” remarked Adegbite-Moore, who wants to see improved funding models for creative enterprises in Nigeria.

Tilley-Gyado believes that by pulling together, women in the creative industries in Nigeria can help this happen.

“The #WEECreateAfrica campaign has a tagline called ‘Community over Competition,’ but it has also become a lifestyle for me. I relate to other black women, both as sisters and as friends,” Tilley-Gyado said.

“It’s so easy to help another young lady if you’re relatable.”