THE Oromo are the largest ethno-national group in Ethiopia, accounting for over 40 million people or more than one-third of the population. However, they have been politically oppressed, economically exploited and culturally marginalised under successive Ethiopian regimes. Since the 1960s, the Oromo have sought self-determination through various forms of resistance, such as armed struggle under the banner of the Oromo Liberation Front.

Music has played a key role in the Oromo resistance movement. As is the case in many other societies – especially those where open political debate is risky – music serves as an instrument of defiance, allowing artists and their fans to stand up against dominant socio-economic, cultural and political forces. From legendary musicians to amateur singers, Oromo artists have used protest songs as part of their struggle for freedom, justice and equality.

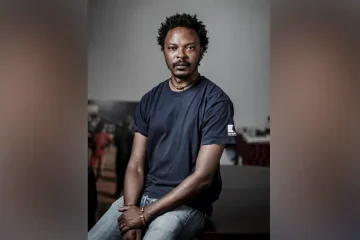

Hachalu Hundessa (also written in the Oromo language as Haacaaluu Hundeessaa) was one of those musicians. Through his poetically eloquent protest songs, the young singer-songwriter came to represent the Oromo struggle. Then, in June 2020, he was murdered. Three men were convicted for the crime a year later, but no motive was given. Many believe it was a political assassination.

Hundreds of thousands of young people across Oromia, Ethiopia’s largest regional state, took to the streets in protest, demanding justice for Hachalu. Members of Oromia’s large diaspora also staged protests in US and European cities. The Ethiopian government used the protests and ensuing violence (reports at the time suggested that more than 80 people were killed) to justify its crackdown on Oromo opposition political parties.

As a political geographer, I focus on the struggles of the dispossessed and their covert and overt forms of resistance – one of which is protest songs. After his death, I studied three of Hachalu’s works: Maalan Jira! (Do I even exist!), Jirra! (We are still there/alive!) and Jirtuu? (Are you there?). My interest goes beyond mere scholarly analysis; there is an emotional attachment there, too. I was part of the Qubee Generation, the youth cohort that spearheaded the 2014-2018 Oromo protest movement to which Hachalu’s songs added inspirational impetus.

In the resulting paper, I show how Oromo protest music like Hachalu’s reveals a history and geography of violence through land dispossession and political persecution. It is also more than just a record of events in time and space: protest music forges collective identity and spurs political movements. I also strive to comprehend what a musician like Hachalu Hundessa represents – and what it means to destroy a body that embodies the power of resistance.

Three key songs

Hachalu Hundessa was born in Ambo Town, some 120 kilometres to the west of the capital city, Addis Ababa, in 1984. He was active in Oromo student movements when he was at secondary school and was imprisoned by the government when he was just 17 years old, spending five years behind bars because of his activism. While in prison he worked on his first album, Sanyii Mootii. It was released in 2009 and immediately made him popular.

The first song I analysed was Maalan Jira! (Do I even exist!), the title track from his 2015 album. He tells of the occupation of Finfinne (what is today Addis Ababa) in the 1880s that dispossessed the Tulama Oromo clans, displaced them from their ancestral homes and sacred places and dismantled their social institutions.

He takes the listener or viewer through a mental map of history. The lyrics can be viewed as a struggle to dismantle institutions and discourses of settler-colonial systems long imposed by the Ethiopian state upon the Oromo. The murder of Hachalu, then, can be interpreted as an attempt at silencing counter-histories in Ethiopia. https://www.youtube.com/embed/Wv3he6CGF3E?wmode=transparent&start=0 Malaan Jira, the title track from Hachalu’s 2015 album.

The second song in my paper, Jirra! (We are still alive!), was released in October 2017, when the Oromo protest movement was at its peak. He underscores the determination of the Oromo, locating the resistance in physical places. He does this by naming places where the movement had a strong presence, articulating the convergence of different corners of Oromia towards the goal: liberation.

The third song, Jirtuu? (Are you there?) again exposes the historical events related to land dispossession and political oppression. At a live performance in December 2017, during a fundraiser in Bole for Oromos displaced by clashes with the neighbouring Somali region that year, he asked the crowd: “Where are you?”, then encouraged them: “Say we are in Bole!” The crowd cheerfully echoed his statement. https://www.youtube.com/embed/D1qiF8Q_usI?wmode=transparent&start=0 A live performance of Jirra!

This was not just a singalong. Bole is a district of Addis Ababa, home to wealthy people who settled on land expropriated from Oromo farmers. The performance was a declaration of the Oromos’ right to self-determination and a call that they should one day control the Imperial Palace – the offices and residence of the Ethiopian prime minister.

The lyrics include:

Kaafadhu farda keetiin loli, Arat Kiiloof situu aane (Fight with your horse, you deserve Arat Kilo – the national palace); Kaafadhu Eeboo keetiin loli, Arat Kiiloof situu aane (Fight with your spear, you deserve Arat Kilo)

Why this matters

My analysis reveals the power of Hachalu’s protest songs in unsettling dominant narratives and institutions, and in serving as a strong instrument of the Oromos’ political and social movements.

His music intertwines time, space and identity. It renders the reconstruction of the past and the imaginations of the future amid contemporary uncertainties. In doing so, music serves as an archival library of the past, a platform of the present, and a mirror of the future.

- This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.