A South African violist has used music and art to explore the painful legacy of how labourers at wineries in the Western Cape province were for centuries given wine as part of their payment, a practice known as “the Dop System.”

The system, which began at the time of slavery in the 17th century and persisted until the recent past despite attempts to abolish it, caused high rates of alcoholism among mixed-race workers who for historical reasons were the main labour force at the wineries.

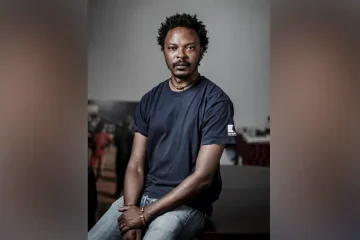

Violist Lynn Rudolph said they wanted to expose how the practice, introduced by Dutch colonialists and maintained under apartheid, had damaged the mixed-race community’s culture and entrenched harmful stereotypes.

“When you think of a coloured (person), and what I’ve seen on social media, TikTok, all these things, to be coloured means to be violent and means to be drunk,” said Rudolph, who goes by the stage name Daphne.

The term “coloured”, considered racist in some cultures, can be used in a neutral way in South Africa to talk about people who are of mixed race.

Rudolph created and performed in a show called “Dop is my Taal”, which means “Alcohol is my Language” in Afrikaans, at an arts venue in Johannesburg.

The show involved Daphne playing music she had composed, interspersed with excerpts from the South African national anthem, while another musician performed using beer bottles, domino pieces and thimbles — objects associated with the daily lives of farm labourers.

At the back of the stage, videos were projected of traditional dances performed by people from the KhoiKhoi and San indigenous communities, who are rooted in the Western Cape and were among the first to be put to work at wineries after Dutch colonialists introduced wine-making to the region.

Rudolph said this was important because the identity and culture of these groups, who are part of the make-up of the coloured community, were long suppressed by the colonial and later the apartheid systems.

“Growing up, my experience of being coloured was that we never spoke about our Black ancestors. It was always just that you acknowledged ‘yes, you’re quarter Spanish, you’re quarter this or that’,” Rudolph said.

“So how do we even start to break down our identity?”

Kelly-Eve Koopman, a writer and social justice activist, said the Dop System had created a cycle of dependency, subjugation, poverty, abuse and high rates of fetal alcohol syndrome whose impact was still affecting communities today.

“Those social effects are immense and absolutely heartbreaking,” she said.

Audience members at the performance of “Dop is my Taal” said the work had articulated uncomfortable truths and given expression to a part of South African society that sometimes feels marginalised.

“For me, it really registered in so many ways because we struggle to fit in,” said Julia Zenzie Burnham. “I love the fact that she’s taking it upon herself to do a work that speaks for so many other voices.”