[tta_listen_btn listen_text=”Audio” pause_text=”Pause” resume_text=”Resume” replay_text=”Replay”]

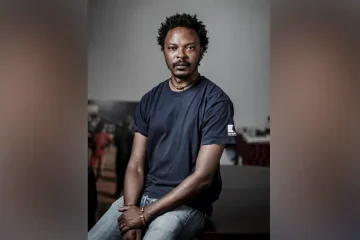

TSITSI Dangarembga is a Zimbabwean playwright, filmmaker and award-winning novelist who is vocal about freedom of expression and human rights. In 2020, she was arrested and later convicted by a Zimbabwean court for inciting violence after carrying out a march calling for political reforms. The charge was later overturned.

Her first book, “Nervous Conditions” earned her the Commonwealth Writers Prize, with the New York Times calling it one of the 20th century’s most significant works of African literature. Other works include “This Mournable Body”, “The Book of Not”, and most recently, a book of essays titled “Black and Female”.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Congratulations on publishing your first nonfiction book, Black and Female, last year! How was the transition from writing fiction to nonfiction? Could you share your experience?

When I came to study Film in Berlin in 1989, I came to do a practical course, but some of the things that were part of the curriculum at that time made me wonder why they were in the curriculum. For example, one of the films we were shown was the 1915 film, The Birth of Gretchen. I was completely shocked that they were presenting it as a teaching tool because it was deeply racist. Even when it was released in the USA, some states banned it because it was too racist. That experience made me learn what I could about film theory independently.

Since then, I have published a few articles on film theory, looking at feminist film theory from an intersectional perspective. I have published two or three articles, and I do quite a lot of public speaking on these issues. I have been working in the area of nonfiction since the 1990s, but I simply have not put together a volume that contains my work exclusively. Black and Female was simply me going back to all this work that I had been doing since the 1990s and the speeches I have given on the continent, especially in South Africa.

In the book, you write, “what writing while black and female does constrain for me is access to publication opportunities, and when I am published, avenues to reputable, professional publishing houses and lucrative contracts, money being the currency of empire.” One would think that with your reputation in the industry, you would not face these problems at all. How have you navigated this?

I have not managed to navigate it as such. About twelve companies own all the publishing houses in the world, the big publishing houses. Of course, independent publishing houses go at it on their own. When one sees that power is accumulated in one area, one can imagine that the policy that flows from this power will be uniform. Whether we like it or not, there are other powers in the world at the moment, but in terms of controlling the narrative of what the rest of the world sees, the global West is still doing that.

So while there is more publishing of black women now compared to when I began and my role models began, people like the late Ama Ata Aidoo. There are now more opportunities, but my thinking is that the narratives allowed by these publishing groupings decide on the same kind of narratives because these are the narratives that suit their purposes. While it is good that more female voices are being heard and that they are diverse in terms of demographics and age, I still think that the content is not as diverse as it could be or should be to introduce more ideas into the world.

Just think of it, there is an emphasis on slavery, and I find this very sinister because it is an emphasis on recalling how one was powerless and became enslaved. It is never happy to recall the moments of your powerlessness, to use those moments of powerlessness as an emblem. There is the whole institution of slavery that the global West instituted beginning with the Portuguese; it was an economic imperative. But it also had philosophical roots in the Enlightenment.

This grouping of publishing houses is coming from that philosophical position, and so for them, slavery is something that is self-aggrandising. There is a psychological play of making people talk about how these people have enslaved them.

I would like to ask your opinion on AI technology. How do you think African writers should approach the use of this technology?

There could be a certain type of writer that is using AI to generate material. But it’s not the norm for all writers… I do feel that AI doesn’t serve humanity; it may serve science and certain groups of people with a vested interest in the kinds of data and ways of analysis AI should do. But a tiny percentage of the human population has any input in any of that. AI is serving a very small percentage of the population, in my opinion.

The International Images Film Festival for Women (IIFF), which you founded in 2002, is now in its 20th edition and has boosted numerous female filmmakers. Is there anything you wished you could have done for the festival but haven’t been able to yet?

It’s been challenging to keep the International Images Film Festival running because moving image content is a very powerful medium as it is primarily visual. This makes film a very potent industry for manipulation and propaganda. Since it’s resource-heavy in terms of capital, it tends to be those people who have power and who have that money and use it for their agenda.

I have not had much support for this. Support came from the EU from 2013 to 2015, but immediately after that program ended, they changed how they do it. My thinking is that they thought this gave too much autonomy to people who were not the people that African governments wanted to be supported. So there was a move to change how this was done.

It’s been very difficult, last year I had to fund the festival individually, which was such a disaster for me. We were coming back from Covid 19, and there was some interest from others to say they would fund it. But in the end, most of that did not happen. Some people are working in that office, and if that office closes, it means those people are jobless.

This year, so far, we have 25,000 US dollars from the Culture Fund specifically for the festival, which is wonderful. We will do something with that 25,000 dollars, but there is definitely not much support for women’s voices in film. It turns out that I am probably one of the most highly educated and experienced people in the film industry in the country. Normally, that is of value to people who place value where value is, but not in Zimbabwe. Our values are different; it’s not about people telling stories; it’s about politics. So those values follow political avenues.

Throughout the years, you’ve received numerous awards and honours. Do you have any other prizes you hope to win, such as the Nobel Prize or something similar?

I don’t write to receive prices; I write in the hope of telling meaningful stories that touch other people and are beautiful to other people. That, for me, is the most important thing, and it’s important for me to strike an encouraging tone in my writing. My writing can be depressing; it can say ‘It’s really hard, but there is still something that you can do’; for me, it’s the core of my philosophy of life.

What is your opinion on the extent to which awards shape an author’s career?

Awards have an impact in terms of having more visibility and impact and more people buy-in, which is why I was able to fund the film festival last year. If it had been ten years ago, the festival would have folded, but because of the impact of the prizes, people became interested in my writing. I was able to say to my team the festival must go on to the extent of bringing women from Pakistan and other countries to participate.

The negative side is that one has to fight or resist in some way the effect of the experiences of always being asked to speak, engage with people and remain rooted. That is very difficult in a country like Zimbabwe, where free thinking is discouraged, and people who insist on their right to use the brains that God gave them are persecuted. It becomes difficult to remain rooted, so that is one of the problems I am currently facing.

You’ve led many protests against the government of Zimbabwe, rightly calling for reforms in institutions. What would your ideal Zimbabwe look like?

I don’t think my protests are against the government of Zimbabwe. That is media rhetoric. My protests are individual utterances suggesting what I would like to see. It’s really interesting that in Zimbabwe, an individual saying what they want to say is immediately seen as an anti-government protest, which is ridiculous. This should lead to debate.

I see how I live and how other human beings live; I think living standards should be better for the average human being in Zimbabwe. People should live better than how they are living.

In this era of social media, many people prefer to air their dissent online. Do you think online activism is as efficient as physical on-the-street protests?

It depends on the country; if you have people who respect people’s human rights, opinions, right to life, and dignity, then I would say physical activism is more effective. We see that in countries like the USA, for all its faults, including the way it is structured politically, which is a compromise on democracy, there is room for people to stand up because the nature of the people allows them to stand up.

There are other countries where people believe the public space deserves to be occupied, so they engage publicly.

Unfortunately, we don’t have that culture of coming out in Zimbabwe. We have a culture of saying if you go out there, you will get into trouble and lose one day of working for your family, which is a close-sighted view. So you work this day for your family, and you earn, let’s say, 3 US dollars which will buy – if you are lucky enough to have – sadza (maize meal) and vegetables. If you did go out, you would suffer, but you could change things to give your family decent food and other social goods for the rest of their lives. It’s a way of thinking that we have that prevents us from going out. There are reasons, and I think the government understands the psychology of the Zimbabwean person and exploits this to the maximum.

I do not actually think Zimbabweans could get to the stage where they could fearlessly go out en mass. I think it would have a positive effect, but I do not think we are at that stage.

What are you passionate about lately? Do you have any hobbies or interests besides writing that bring you great joy?

I am also a producer of narratives; I love filmmaking. I’m also trying to establish collaborations in writing scripts; I love the production process where many people work together to make something, a beautiful story, happen. So really, I like producing narratives and stories. I like to engage in efforts to expand my spirituality, which is something else that is very important to me.

What are you currently working on/or involved with?

I have this particular script that I’m working on alone. It takes me a long time to get into it, but when I do, and the characters start speaking, I feel compelled to write. One of the scripts I’m working on has got to that stage. Then I have a couple of international productions I’m working on, Kenya, Germany and several things going on. I have another nonfiction that I’m working on; it answers how we Shona people come to be who we are and manifest what we manifest. This question led me back to this group of people who are said to be Bantu language speakers. That is my ongoing nonfiction project while I do these other things; I have a lot to do now. Currently, I am a Research Associate at Stellenbosch (University); it should take me around five years to finish my Bantu project.