NTOMBIZIKHONA VALELA

ZINDZI Mandela comes from a family of writers. Although her parents were not writers by profession, this craft was a crucial way of keeping their family together. Mandela was barely 18 months old when her father, Nelson Mandela, was arrested on 5 August 1962 after being a wanted man for his role in South Africa’s liberation movement. His life sentence following the conclusion of the Rivonia Trial in 1964 was served on Robben Island, which meant he could only communicate with his wife, freedom fighter and social worker Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, and children through writing letters.

These initial circumstances formed the poet that Mandela became.

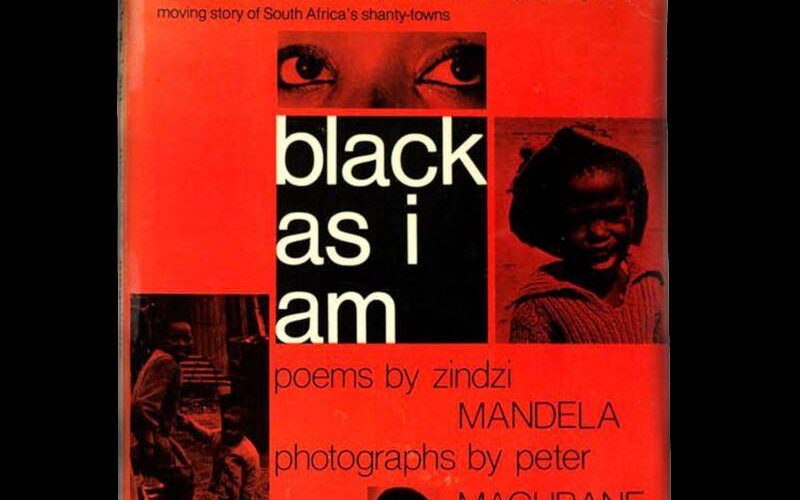

Her poetry anthology Black As I Am opens with A Tree Was Chopped Down, which pays tribute to her father. It also explores the effects of growing up in a family whose structure had been bulldozed by the apartheid regime. The restoration of the black family structure, heteronormative at the time, was an important aspect of the liberation movement. South Africa’s economy was built and continues to exploit parents living away from their homes for economic reasons. Under apartheid, influx control worsened the conditions of families because of restrictions on living together in urban centres.

For children like Mandela and her sister Zenani, the fight for liberation tore through their families in the form of banishments and years of incarceration. When Black As I Am was published, the 17-year-old poet was with her mother in Brandfort, where Madikizela-Mandela had been banished.

In the wake of Mandela’s death on 13 July, it is curious that A Tree Was Chopped Down was the sole poem that circulated across South African news publications. Reports linked her to her father, and barely any portraits of a life as more than an extension of her iconic parents were circulated. Yet she always saw herself as both connected and separate to this identity.

As quoted by Mary Benson in the book Part of My Soul Went With Him (1986), Mandela says: “I have suffered like every black child has, so I have a certain duty and role to play in my own society – independent of my being Mandela’s daughter.” That this “duty and role” has yet to be expansively explored speaks to the problematic ways in which we document history.

Although 17 at the time her anthology was published, a few poems were written when she was as young as 14. A second anthology, Black and Fourteen, a compilation of poems written at that age, remains unpublished. Black As I Am placed her in a tradition of important creative work at the time. In addition to this anthology, Mandela contributed to various collections, including Margaret Busby’s Daughters of Africa (1992).

Writing in defiance

By the time Mandela began writing, the tide of literature had turned from only exposing the brutality of the apartheid regime. There emerged writing that seemed to talk back with defiance against oppression. This wave, ushered in by the Black Consciousness movement, also produced writing that affirmed black people who had long been classified as non-persons. The trade union movement of the early 1970s also became fertile ground for this artistic renaissance. Rallies became spaces for the performance of poetry and plays, and the circulation of writing in mostly pamphlets and publications like the Black Review of the Black People’s Convention. The influence of the movement and its writers – the likes of Mongane Wally Serote, James Matthews and Oswald Mtshali – are visible in the work we see in Black As I Am. Its very title hints at this.

By the time the anthology was published by Guild of Tutors Press, a small publishing house in the United States, black South Africans had morphed from natives to non-white then to plurals. These were all classifications about which black people had no say, and they all reinforced the ideas of not belonging and inferiority to white people and whiteness.

The literary production by black poets, novelists and public intellectuals from Steve Biko to Miriam Tlali were acts of oppressed people reclaiming the right to name themselves. Black As I Am is thus an affirmation. Mandela, as young as she was (she is among the three youngest published poets in South African history), making this claim also speaks to the era that made such a feat possible – the student-led Soweto revolts of 1976 of which she was a part.

Further, the use of free verse in her writing style is in tandem with the work of her iconic colleagues who preferred the imagist style to deliver a message that was clear and consistent with the language and cadence of the time. These were not simply poems that reflected black life, they were rooted in a specific tradition of poetry writing and were complementary to the lexicon of black people.

Depicting complex experience

Mandela, through her writing, documents the struggle for human dignity from the perspective of a young black girl. Each poem is accompanied by piercing photographs by Peter Magubane, whose career was dedicated to capturing life under apartheid – both its brutality and the ways in which black people lived in joy and pain. Here, in pictures that depict the daily lives of township residents in the middle of the crime against humanity we know to be apartheid, children are laughing, probably not in the face of “life’s ups and downs”, to borrow from Mandela’s poem Yes It Is Me, but because even in the belly of the beast were human beings living and simply being.

Magubane’s lens offers an important nuance typical of the Drum-era photojournalists who told layered stories of black life, from children playing in the streets to congregants gathered for a baptism service at a nearby stream.

In historical records, not only do we barely hear the stories women have to tell, we also almost never hear the perspectives of children, except perhaps as adults looking back. I Saw a Child is a meditation on the awareness a black child has of the difference between them and their white counterparts, and it speaks to the childhood of which black children like Mandela were robbed. – NEW FRAME