KARABO KGOLENG

LINDIWE Nkutha has small feet. For the longest time, she coveted a pair of All Star takkies but she couldn’t find a place that sold them in her size. One day, her partner – raised in Pretoria – suggested they go to Marabastad to look for them.

They found the shoes in Marabastad’s Jerusalem Street, a place that evoked for her an atmospheric combination of Diagonal, Bree and Noord Streets in Johannesburg. Anyone familiar with these streets knows they are sites of enterprise, bustling with crowds of diverse people on different missions, hooting taxis and the obligatory dodgy, noisy taverns full of weary workers exchanging their meagre wages for momentary relief.

On Jerusalem Street, Nkutha saw a man hawking from a shack with a sign above it that read, “Never Die”. There was also a residential area close by, giving to the place the ambience of township life and to her, the inspiration to tell stories about everyday people with extraordinary lives embedded in South Africa’s varied and contested histories.

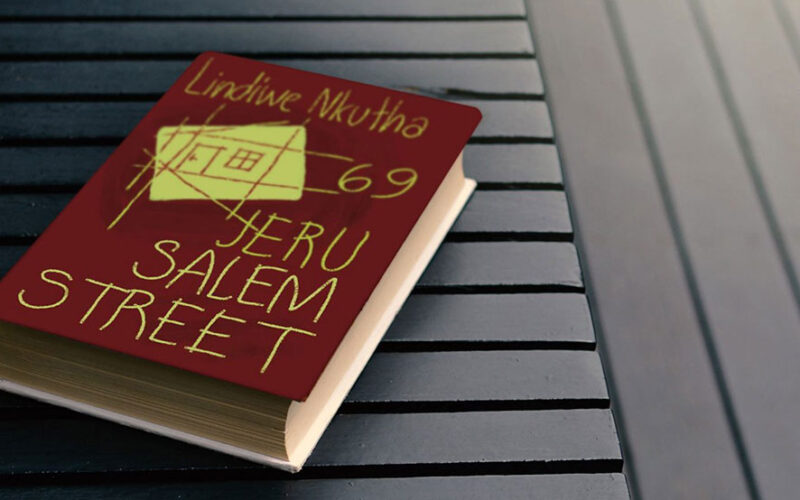

The resulting book, 69 Jerusalem Street, tells feminist tales that pay homage to the “never die” nature of the craft of storytelling, with a focus on disability and sexual rights.

Nkutha is also attracted to the symbolism of Jerusalem, a place sacrosanct for the people of the Muslim, Christian and Jewish faiths and simultaneously politically contested at great and often fatal human cost. It is against this backdrop that she created its metaphorical representation, the house on 69 Jerusalem Street, which is the short story after which her anthology is named.

Imaginative histories

This self-taught historian deftly works with metaphors in the naming and creating of her characters throughout the book. In 69 Jerusalem Street, Rasputin is the villain who, like the historical figure, “is a bit of a shyster and not lovable and not kind”. The collection is an entertaining study in “pulling from historical figures to give depth to fictional characters that might have embodied the traits and characteristics of their historical counterparts”. It is Nkutha’s way of making sure history never dies.

Jocasta’s Hairballs was previously published as a stand-alone novella and the characters are partly inspired by women in African, Roman, Greek and Christian mythologies. Nkutha explains, “A little known fact about Jocasta is that she was Oedipus’s mother and I thought, when a lot of women in these mythological tales are named, they are usually called so-and-so’s wife or they are identified as the woman with the [undesirable] issue. Once I found Jocasta’s name I imagined what would happen if the story was to be told from her perspective and it was her who had the luxury of bringing people in [to the story] instead of the other way round.” In this way, Nkutha centres the woman character as a means of challenging the patriarchal storytelling practice of using women characters as props when they are not antagonists. “I wanted to explore and exploit mythology from a feminine point of view,” she says.

The Jocasta of Nkutha’s imagination fights crushing battles against grief from miscarriage, postpartum depression and her husband, Vido’s, violence and infidelity. Nandi, another character in the story, epitomises a woman’s agency in a similar way to her namesake, Shaka Zulu’s mother. She tries to reach out to Jocasta, helping her see the possibility of a happier, self-sufficient life by using her personal history as an example. Delilah is Vido’s mistress who, as the story unfolds, begins to regret her decision as he shows his destructive nature.

Reading Jocasta’s Hairballs can be a bit confusing for those who like their stories to stick to a single literary technique. Nkutha says hers was inspired by Greek tragedy. She delivers the story by way of the characters telling their versions and reflections on the tragedy in monologues and poems. She says, “It’s almost like a little orchestra in my head where I’m juggling these characters … like I was conducting an orchestral Black Greek opera where different people enter the stage [and] exit the stage.”

Transitions and blending

“Unlike most people he knew whose biggest fear was death, his greatest dread was old age.” This is the opening line of Black Widow, the story of Ou-diePinkies, a cobbler with a broken heart who “spent most of his twilight years mending the holes on the soles of other people’s shoes … in order to detract from the gaping hole in his own heart”. The hole was formed when his lover, Afsar, left when he was 32 years old. The events leading to his departure, in the manner of real-life love stories, could be described as a mess – or in social media speak, “yifilim!” (“it’s a movie!”) Now, in his sunset years, Ou-diePinkies receives a letter from Afsar’s husband, a doctor who was a pioneer in gender reassignment surgery. The letter is an announcement and a request for her shoe.

“I realise that people who read the story might fix it on [gender] transitioning,” says Nkutha. “But I feel like it’s not the most important part of the story. It is significant but it is not the most significant part and I think that the role that it plays is that in this narrative, the LGBT community has [always] been alive.” She uses Black Widow to counter the narrative that presents the history of LGBTQIA+ as only as old as South Africa’s political liberation. “That’s me saying LGBT lives are not a fad or something new.”

Black Widow also allows the reader to witness Ou-diePinkies’ nostalgia for the era of his youth. He recalls his journey to Durban by train, the most common form of long-distance transport at the time, reflecting on the ritual-like process of buying the ticket and having it stamped followed by the conductor checking and punching it while on board.

Nkutha explains, “I wanted to move away from telling primarily the postapartheid story, which has become a preoccupation of a lot of people. I wanted to go back in time and tell a historical tale from the perspective of a person who is ageing and looks back on their lives.” This tale also imagines the lives of South Africans in the 1950s alternatively and in addition to the popular narratives of Sophiatown and District Six. Nkutha hopes that there will be more historical fiction featuring characters with diverse gender, sexual and social identities.

In 69 Jerusalem Street, Nkutha explores themes that infuse everyday life but help us think about, for example, the etymologies and reasoning behind the names we carry and whether we come to embody those names, the spiritual and religious syncretism that we practice overtly and in secret, and how the vulgar can also be mundane.