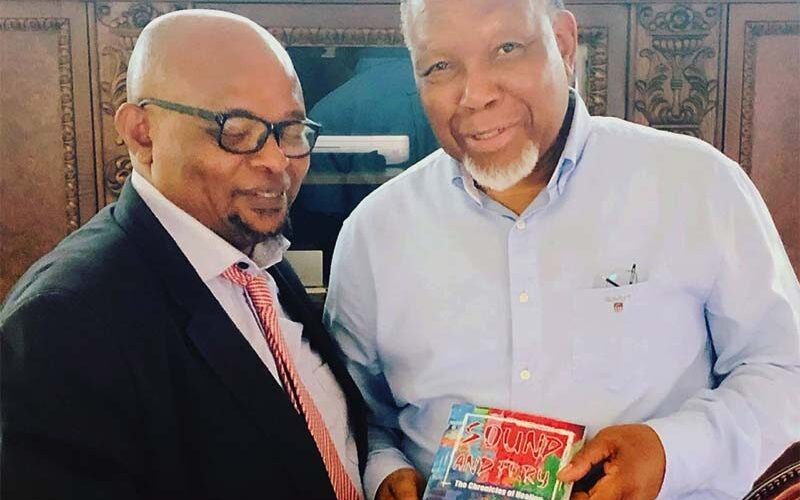

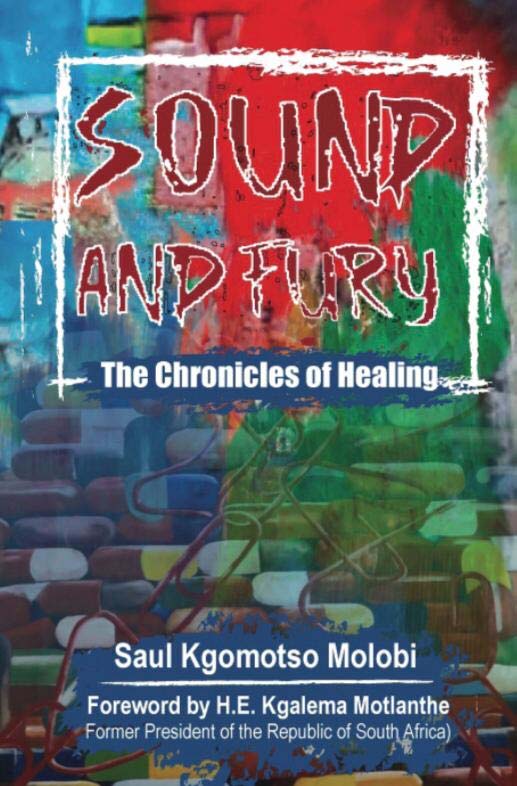

In this chapter extracted from his newly published hospital memoir, “Sound and Fury: The Chronicles of Healing”, SAUL MOLOBI looks forward to spending his weekend break from the Tshwane Rehabilitation Hospital with his mother – they are both disabled and using similar assistive devices…

Though I love my Fridays, this is a special one since I will be spending this weekend with my mother, Kadimo Jane Molobi. This shouldn’t make me sound like a momma’s boy. I am not.

Besides, I grew up hearing all people, including my late dad, fondly calling her ‘mmaKgomotso’ (Kgomotso’s mom) to the extent that at one stage I even thought it was her real name.

Another piece of good news is that I will for a consecutive weekend be parking my Ferrari and pushing the roleta. My mother uses it too. So my mom and I are going to stage a Formula 1 race as we turn the house into a Kyalami Race Track.

The other good news is that I will soon be like the nyaope addicts and go pawn my Ferrari [the author gave this name to his wheelchair] to one of the China Shops. I will deal with my debt for it with the Tshwane Rehabilitation Hospital later.

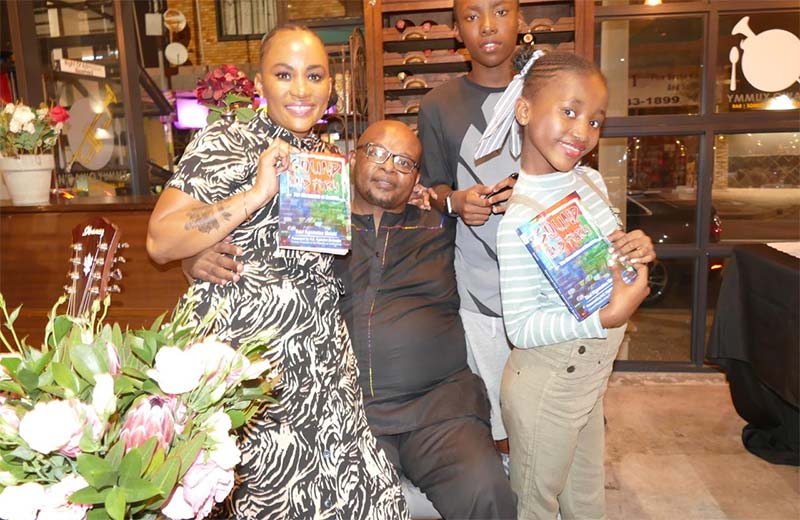

Last weekend Lilly ( my seven-year-old daughter) remarked when she first saw me walking into the house: “You walk like koko”. To which Tshiamo (my eleven-year-old son) responded quickly: “But faster”, as if that would make me feel good.

Since these children are so competitive and see me as a hero in one of their PlayStation games, I hope my mother, with her vast experience of pushing the roleta walker, won’t embarrass me by outrunning me. If she does, I will negotiate with her regarding the rerun match that I will win. I’m hoping Tshepo (my wife) won’t report us to the Gauteng Gambling Board for match fixing.

But who is my mother?

My mother gave birth to nine children, five girls and four boys. I was the fifth child, though my elder brother, Michael, died in his infancy, making me what in Setswana we call “ngwana wa ngwato”, which loosely translated means a child who was born to replace the child who passed on. According to our Setswana tradition, to safeguard me against bad luck, my whole head could never be shaved. There always had to be a small patch of hair. My peers at school used to tease me all the time when they spotted this.

Though she was born in Alma, a one-train-station-one-grocery-shop rural town between Modimolle and Lephalale in Limpopo, she was raised in Kraalhoek, whose nearest town is Rustenburg. This was after her mother had passed on and she went to live with my youngest aunt, Matlhomola; while Timothy and Tiny, her other siblings, were separated from them and raised by another aunt.

My mother is a very strong willed personality, sociable and an extrovert. A strict disciplinarian. She literally raised us all as my father, Samuel Molobi, only visited us on weekends as he was a migrant worker. Sometimes her strict Calvinism meant she would also try to choose friends for me. This was the one battle she never won.

She was uncomfortable about my tendency to befriend guys who were much older than me, such as Mogomotsi Molefe. He had dropped out of primary school, so I guess her fears were that I would also quit school and even start drinking alcohol like he did. I used to share a desk with him. The truth is that she was right in some instances. I did experiment with alcohol at the age of thirteen and tried smoking marijuana. All this with him.

Mogomotsi and I mostly hooked up in the afternoons and on weekends. During the day, my bosom friends were my classmates, Selemogo Maleho and Solomon Kekana.

I loved Mogomotsi because he was like a big brother to me, protecting me from the village bullies. He also worked for the dry cleaners, collecting clothes from villagers on a bicycle and later delivering them. The delivery beat I loved because he would buy me nice things like sweets, cold drinks and even “vetkoek”. He loved sending me to go call his girlfriends for him. Remember in those years teenagers were not permitted to date like nowadays. I soon perfected the art of sending messages to his girlfriends without the elders realising I was up to mischief.

My financial dependence on him eased off after I started working as a gardener on Saturdays in Wierda Park, in today’s Centurion. Though I felt rich, I still needed him for protection. We remained buddies up to today although our power relations have changed in my favour. Each time I go to my village, I know I have to offer him something to keep him afloat. Times are tough particularly for ordinary labourers like him. Occasionally we tease my mother about those days and how our relationship survived her dislike for it.

What drove a slight schism between us was when I passed my Standard Five (now Grade Seven) with less than satisfactory marks. My daytime classmates and friends passed with flying colours. I was very embarrassed when the principal announced that I got a third-grade pass.

At junior secondary school, I continued with my peers as my friends but also befriended the school’s senior students. The seniors, particularly the late Phillip Masombuka and Elijah Teffo, became my positive role models. I followed in their footsteps to become one of the best debaters in my class. Like Maliwa, I became the chairperson of the Student Christian Movement. In the evenings I went with them to study for exams.

The end of year exam results came. I passed well. I was in the overall top ten of all the Grade 8 students and was happy to rejoin my peers in Grade 8A – during those days, intelligent learners were placed in A classes. My mother was happy about my new friends although they were older than me. What impressed her more was that they were now students in high school when I was doing Grade 8. She also got feedback on my excellent performances in the debating teams.

The other person who had a great influence on my life was my cousin, Oupa Dube, the son of my mother’s sister in Rustenburg who came to live with us in New Eersterus. He was a teaching student at a college in Hammanskraal. He always insisted on speaking to me in English. He was also the one who introduced me to community theatre as he established the first drama group in our village, something that provided an alternative form of entertainment to soccer in a dull rural village without any entertainment amenities. The other form of entertainment at the disposal of villagers was booze which was plenty. Maliwa also became his protégé.

My relationship with Maliwa and Elijah died down a bit after they started dating my sister, Emily, and my cousin sister, Miriam (the daughter of my rangwane, my father’s younger brother), respectively. For some reason I felt betrayed and was protective over my sisters. Their relationships with them became serious as they bore children. Though I never disliked them, I drifted apart from them.

I was still talking to Maliwa (may his soul rest in eternal peace) also as a comrade until his untimely passing on in 2015. I still communicate with Elijah through Facebook and still call each other fondly, “Anja” (a Zulu word meaning my top dog), like we used to do when we were close buddies. I love my niece, Lucky Molobi, Emily’s daughter, and my nephew, Kgothatso Molobi, Miriam’s son. It’s a pity I couldn’t attend Maliwa’s funeral as I was living in Italy. I haven’t seen Elijah in a long time since he now lives in Mpumalanga. I am glad to say both of these gentlemen took responsibility for the maintenance of my niece and nephew and today they have blossomed into promising youngsters.

The paradoxes of life are that I wasn’t too keen on them dating my sisters but I still got hurt when they separated. Perhaps that’s a brother’s love.

Back to my mother, she was elated with the turnaround in my life. She was also happy that I was a gardener on Saturdays and taking care of my own school financial burdens. In those years, rural villagers had to pay annual school fees and contribute to a school building fund as government only provided for the payment of teachers. The rest was the responsibility of the village elders. Because of the extreme poverty in our village, there were many intellectually gifted children who dropped out of school because their parents couldn’t afford to pay all these fees. One such example was Shadrack Ratau, the first person to introduce me to the concept of black theology.

My father used to bring us peanuts from his sojourns in the present Limpopo. My mother would fry them and I would sell them to the villagers, particularly at soccer games on Sundays. I then saved money from gardening wages and bought a camera that I used to take photos of schoolmates and which I then sold to them. This helped to augment our household income. My mother just adored me.

My father, through my mother, turned our home into a warm nest not only for us, but for my friends and many other people in our village. I know I am home, at my parents’ house, where I was brought up, when a distant neighbour blasts music so loud that you even hear it through the ear that your ENT specialist has confirmed you need a hearing aid for.

I know I am home when we’re sitting under a tree, and a middle-aged man comes to join us, we drink and eat with him, and four hours later he’s heavily sloshed and staggering, three steps forward, two steps back – as Vladimir Lenin once described it – as he makes his way to the gate merrily bidding us goodbye, and then we all ask each other who he is, and we discover none of us really knows who he is, and we continue indulging in the feast. No big deal!

I know I am home on 2 January of each year, my mother’s birthday, and halfway through the celebration she reminds us that her actual birthday is on April 28. Home Affairs got it wrong donkey years ago when they issued her with an ID. Anyway, the birth year is correct, so what? Yes, she has two birthdays a year: happy birthday, mom!

My mother possesses all the finer qualities that many women can only wish for or the kind that children wish their mothers were gifted with by God and the gods. My siblings and I were lucky to be blessed with such a mother!