KELLY FLETCHER

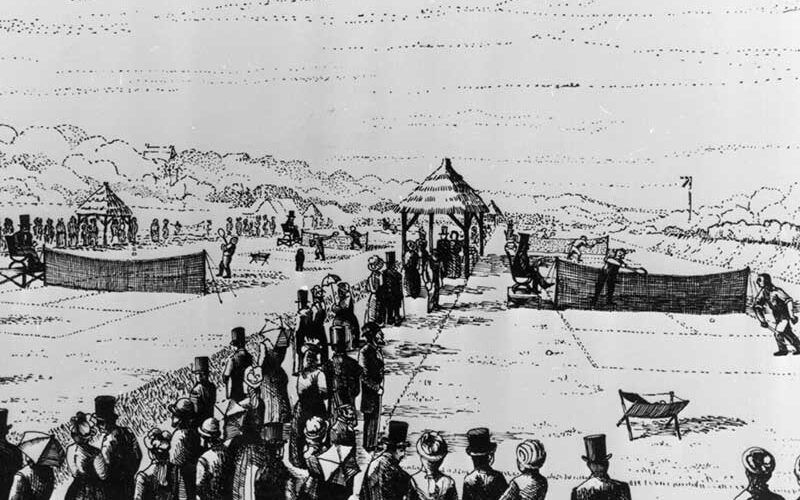

THE first lawn tennis matches were played on hourglass-shaped courts. But not for long. Three years after Walter Wingfield was granted the patent for his “portable court” and began selling his lawn tennis sets, the first Wimbledon tournament took place in June 1877 on a rectangular court. The shape of the court and the scoring system from that inaugural Gentlemen’s Singles tournament is still used today. In other ways though, lawn tennis has changed immensely, as David Berry shows in A People’s History of Tennis.

Tennis is still seen as a sport for the privileged by many today and its roots, certainly those of lawn tennis, uphold this notion. Berry doesn’t shy away from this as he works his way through 150 years of history. But his extensive research reveals the less publicised side of lawn tennis, that of the mavericks and feminists, the socialists and immigrants, outsiders and trailblazers.

Among these were vicars and young women. “Tennis is a sport that inspires deep affection among its devotees … No profession in Victorian Britain was more appreciative of this than the clergy.” Many vicars took up the game, introduced it to their congregations and set up courts on vicarage lawns. Many of the daughters of vicars were encouraged to take up the game at a time when standards for what daughters were allowed to do were changing. The women’s suffrage movement was gaining traction and schools were opening for girls, where lawn tennis “fitted in well to the roster of sports and pastimes”.

The success of the women’s game from this point on is notable, starting with the young women determined to overcome societal and patriarchal obstacles to continue playing. “My mother,” wrote Charlotte Cooper – still the oldest woman to win Wimbledon, in 1907 at the age of 37 – “turned a deaf ear to anyone who advised her not to allow my sister and I to travel about” to tennis tournaments.

Dorothea Douglas Chambers wrote early on that “ladies are catered for very badly … if men had to experience the changing room accommodation afforded for our use there would not be many of them competing”. More dangerous was the Victorian patriarchy, which wanted to exclude women from the game entirely. The minutes of an All England Club committee meeting from the late 1870s reveal that it was “not desirable to have a ladies tennis cup under any circumstances”.

Fortunately, mixed doubles competitions were too profitable and popular “with spectators as well as competitors”. The more than 6 000 people who turned up to watch a women’s final in Dublin in 1884 gave the “dear old gentlemen” at the All England Club “a huge shock”. And when rival club London Athletic announced its first British women’s tennis championship, it prompted the All England Club to hold its first Ladies’ Singles that same year.

Battle of the sexes

In August 1888, a “battle of the sexes” charity match was held in Exmouth, in which future Wimbledon winner Ernest Renshaw played Charlotte “Lottie” Dod, whom many consider “to have been the greatest British sportswoman of all time”. “Renshaw gave Dod two points each game but then he didn’t have to wear the restrictive dress that even the rebellious Dod had to put up with. He won but only just.”

It was another battle of the sexes match 85 years later that would progress the women’s game another huge leap forward.

When Bobby Riggs boasted that he could beat any woman in the world despite his age of 55, Wimbledon champion Billy Jean King responded to his taunts that “the best way to handle women is to keep them pregnant and barefoot” by taking him on in September 1973. She beat him easily by staying on the baseline and pushing him around the court, to the delight of the crowd. She “claimed her victory was part of the feminist struggle of the time”.

King’s sporting achievements are well documented and her struggle against inequality, injustice and discrimination in women’s tennis and society is unrivalled. Her successful lobbying for equal Grand Slam pay at the US Open in 1973 bookends that of Venus Williams finally achieving the same at Wimbledon in 2007, and nine of the 10 highest paid female athletes in 2020 are tennis players. But that tennis match against Riggs has been seen by more people than any other as a result of television.

“The game attracted 90 million television viewers across the world, the highest ever for a tennis match.”

Television a game-changer

Much like television has brought sport back to the fans during the coronavirus pandemic, it was instrumental in bringing tennis to the masses, irrespective of class.

At Wimbledon in 1937, Bunny Austin played George Lyttleton-Rogers in the first round. “The black-and-white pictures that flickered through that afternoon from Wimbledon’s Centre Court were clear enough for viewers to see two men in white hitting a ball across a net. It was the first time a game of tennis had been televised … The sound was better than from most radios.” And “by 1948, Wimbledon was attracting a television audience of 200 000, almost as many as made it to the ground.”

While park tennis was breaking class barriers in America – on municipal courts of “hard cement, asphalt or tarmacadam”, occasionally clay – the expansion of tennis in Britain came through the Workmen’s Act of 1905. This allowed local authorities to hire unemployed people to improve the country’s parks, including by building thousands of public tennis courts.

“My study overlooks one of the largest fields of public lawn tennis courts in Great Britain. Play here begins at half past six in the morning so people can get a set in before work at eight,” wrote AJ Aitken in Lawn Tennis for Public Court Players in 1924.

Another way to “break down the division between white- and blue-collar staff” was through works’ sports clubs. Pharmaceutical company owner Jesse Boot set up such a club in the 1800s, “including a thriving tennis section … to attract talented scientists”. Dozens of British firms followed suit, investing in tennis courts for their employees. “Cadburys had 60 tennis courts in the 1950s” and “in Paisley, Clarks sponsored the Anchor Tennis Club for employees from their textile mills”.

Workers’ Wimbledon, however, “was the most powerful argument that tennis could be enjoyed as much by the working as the middle classes”.

A socialist tournament

Despite a relaxation in social criteria to join a tennis club – most had opened their doors to the lower middle classes by the 1920s – this did not extend to the working class. “So Ivy Noyes and George Deacon decided to set up their own club under the auspices of the Reading Labour Party Sports Association”.

Noyes, a clerk, and Deacon, a small business owner, would have been welcomed into a club after World War I, but they wanted “a tennis club where all their friends in the local party … railwaymen, gas and post office workers, craftsmen and employees at the giant Huntley & Palmers biscuit factory, could play”. In summer 1927, the “first socialist tennis club in Britain” was born.

Wind and rain dominated their first Worker’s Wimbledon tournament, which Noyes and Deacon organised in September 1932, inviting blue-collar entrants from other Labour Party clubs and the youth league, trade unions and the local co-op. But it ran for 20 years, “followed avidly by national newspapers as well as the radical press” and “its finals were watched by celebrities and politicians”.

Three-time Wimbledon champion Fred Perry was from a trade union family and never fitted the mould of “courtesy, friendliness and cooperation” that was expected of players up until World War II. He just wanted to win and “his love of money did not endear him to Wimbledon officials who steadfastly upheld the amateur game”.

But the game was no longer a genteel pastime for the rich upper classes and, like working-class footballer Fergus Suter, tennis players needed to earn if they wanted to travel to tournaments and compete. “As the South African player Gordon Forbes pointed out, entertainers do not entertain for free.”

‘Televised entertainment’

Cash was “flowing into tennis from television in the 1950s and 1960s” and players were no longer competing simply for the love of the game. “Top tennis by then was not only a sport but a televised entertainment.”

The Australians were the masters of getting “paid” to play, from furtive “settling up days” to “earnings from sports or tobacco companies”. Harry Hopman’s working-class protégés Frank Sedgman, Ken Rosewall, Lew Hoad and Rod Laver continued playing the amateur circuit in this way while their American counterparts turned professional. One of the few Americans who remained an amateur, Arthur Ashe, described this life as that of a “tennis bum” at the mercy of tournament officials. But the pro tour beckoned.

“The professional circuit in the 1950s and 1960s was small but the rewards on offer tempted all the best players, especially those from poorer backgrounds. Most eventually succumbed”, including Hoad and Laver.

By the 1960s, Wimbledon was losing its star players, to the extent that “the Championships every July started resembling a qualifying competition for Jack Kramer’s tours”. Kramer was “the most successful of the professional promoters”. Welsh player Mike Davies was British No. 1 but lived on “crisps and Polo Mints” and once slept under a hedge to compete. Kramer’s offer of £3 500 a year for Davies to turn professional was a no-brainer.

Born into the wrong group

As much as tennis had become more accessible in terms of class, there were still groups for which the sport remained out of reach.

Althea Gibson did not fit into the “cosy world” inhabited by the top women players in the 1950s. Her “arrogant play, intimidating power and burning desire to win did not make her a natural favourite”. She endured racist chants on court and “comments about her physical appearance and lack of femininity were not unusual”. The Williams sisters can relate. Despite this, Gibson became the first black player to win Wimbledon in 1957.

It was when she met British player Angela Buxton “on a tennis tour of India in 1955 and formed a friendship that would last 50 years” that Gibson found an ally.

Buxton was Jewish. And like queer, black and working-class people, Jewish players were not welcome in Britain’s tennis clubs. Like Gibson, Buxton “was difficult and did not go out of her way to make friends or be charming to the tennis authorities”. But “within two years of teaming up, Gibson and Buxton had won the doubles championships in Paris and Wimbledon.” Buxton died on 14 August this year, still waiting for membership at the All England Club even though she was a Wimbledon finalist.

Gibson may now have a statue at Flushing Meadows recognising her contribution to tennis, but she “was distrusted [during her professional tennis career] because she made no apologies for being black and successful … It didn’t make her life easier when she refused to … act as a representative for all black people in white society, particularly those like her from poorer backgrounds.” Similarly, Buxton “was never a crusader for Jewish rights and, if asked about it by journalists, said simply that it made her more determined to succeed”. Now, she is hailed as a pioneer against prejudice.

A small gesture

Unlike Gibson and Buxton, Ashe was a natural activist. He learnt to play on public park courts and there were still few black players at the top level in the mid-1960s, “despite Gibson’s breakthrough 10 years earlier”. But he was more popular than her “for his composure on court and his studied politeness after a game”.

Ashe won Wimbledon in 1975, in four sets against Jimmy Connors – a “lower middle-class boy from St Louis, Missouri” – to noisy acclaim. “What was less remarked upon at the time was a small gesture he made after he won. Arthur Ashe clenched his fist in the black power salute … It was a promise of activism to come.”

“Until he died of Aids [contracted by a blood transfusion] in 1993, aged only 49, he devoted himself to social causes … ‘Being black is the greatest burden I’ve had to bear.’” He lobbied tennis governing bodies in the late 1960s and early 1970s to take action against the South Africa Open and wanted South Africa expelled from the Davis Cup during apartheid. The Arthur Ashe Tennis Centre in Soweto honours his anti-apartheid activism today.

A People’s History of Tennis was published shortly before Black Lives Matter gained such traction in mid-2020. It has inspired conversations around the world about inequality – mostly race, but also gender, sexual identity, class and income – and sportspeople around the world support the movement.

Naomi Osaka brought the 2020 Cincinnati Open to a halt on Thursday 27 August when she didn’t feel the tennis world was taking enough of a stand against racial inequality.

It’s another pivotal moment in the people’s history of tennis that would no doubt make it into the sequel, should Berry choose to write it.