[tta_listen_btn listen_text=”Audio” pause_text=”Pause” resume_text=”Resume” replay_text=”Replay”]

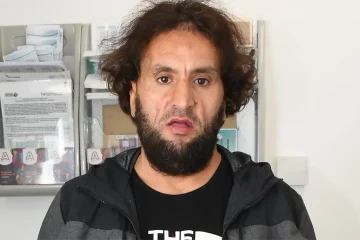

IN working-class neighbourhoods on the outskirts of Athens, Spiros Richard Hagabimana is going door-to-door in an election campaign that could see him become Greece’s first Black lawmaker.

It is a remarkable journey for Hagabimana, who just eight years ago was jailed in his native Burundi for refusing to open fire on anti-government protesters as a high-ranking officer of the National Police.

It would also be a historic win in a country where migrants rarely hold official posts and where, less than a decade ago, the extreme-right Golden Dawn party was the third-most popular political force on a fiercely anti-immigrant agenda.

Dressed in a suit and tie, Hagabimana walks the streets of the constituency he is contesting in Greece’s May 21 election, meeting voters in farmers’ markets and cafes.

“I have an opinion about racism,” Hagabimana, 54, now a senior migration ministry official and candidate with the conservative New Democracy party, told Reuters in an interview.

“Racism cannot be fought with words alone. Racism is fought with everyday actions. When the other person is afraid of the unknown, you must give them an opportunity to come into contact with what they are afraid of.”

In a sign that Greek society is beginning to change, another Black candidate, Nikodimos-Maina Kinyua, the Kenyan-born founder of ASANTE, a non-governmental organization helping migrants, is also running with the leftist Syriza party in Athens, though he is seen as having less of a chance of winning a seat.

The district where Hagabimana is running, which includes the poverty-hit town of Perama and the island of Salamina, just west of Athens, was a bastion of Golden Dawn at the height of Greece’s economic crisis in 2015.

Golden Dawn later imploded and its leaders were jailed over hate crimes in 2020.

For Hagabimana, it meant Greece had turned a page.

“(Golden Dawn) executives were in parliament. Now they’re in prison. I have faith in the Greek people,” he said.

‘I WOULD HAVE BEEN FINISHED’

Hagabimana first arrived in Greece in 1991 on a scholarship to study at the Naval Academy.

When he graduated in 1996, Burundi was roiled by a military coup and he was forced to seek asylum in Greece. He studied law and joined New Democracy’s youth wing.

In 2005, the year he received Greek citizenship, Burundi’s 12-year civil war ended and Hagabimana decided to return to help peacekeeping efforts with the United Nations.

A decade later, the country was gripped by protests opposing a third presidential term. Hagabimana, then a National Police officer, refused orders to suppress demonstrators and was jailed and beaten, he said.

Recalling a night in prison, he said: “I knew if they hit me on the head I would have been finished.”

While in jail, a lawyer friend in Athens launched an international campaign for his release. He returned to Athens in 2016, with the help of Greek authorities.

Hagabimana’s agenda is business-focused, but he also hopes to inspire migrants that “they can be equal members of society… and that everything I achieved, they can do more”.

The colour of his skin should not be the focus, he said.

“It is more important to me that I am a Greek citizen by choice.”