IN bright sunshine, a long queue of shoppers snaked outside an IKEA store near Moscow this week. Similar scenes were repeated across Russia as families rushed to spend their fast-depreciating roubles at the Swedish retailer which is exiting the crisis-hit country.

Russians are bracing for an uncertain future of spiralling inflation, economic hardship and an even sharper squeeze on imported goods.

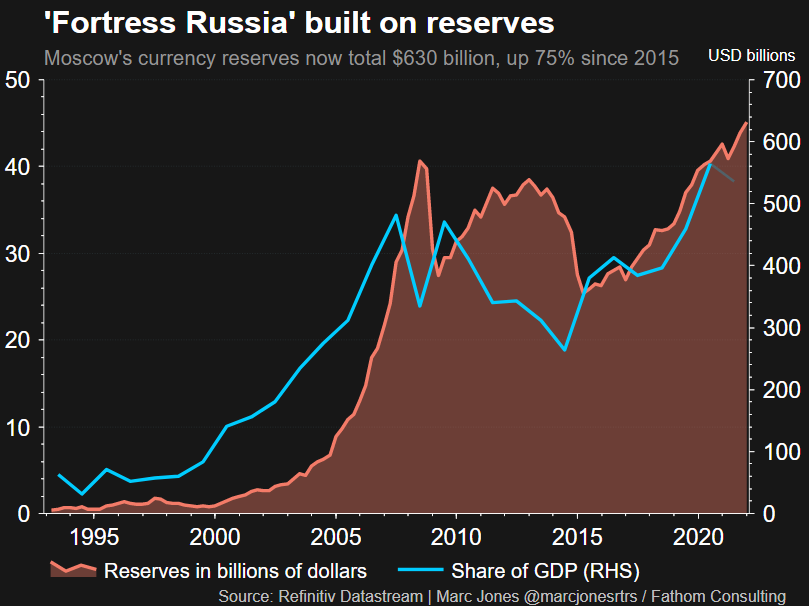

The rouble has lost a third of its value this week after unprecedented Western sanctions were imposed to punish Russia for invading Ukraine. The moves froze much of the central bank’s $640 billion in reserves and barred several banks from global payments system SWIFT, leaving the rouble in free-fall.

Cities across Russia were outwardly calm, with little sign of the crisis devastating financial sector and markets. Except for the lines of people looking to stock up on products – mostly high-end items and hardware – before shelves empty or prices climb further.

“The purchases that I planned to make in April, I urgently bought today. A friend from Voronezh also told me to buy for her,” shopper Viktoriya Voloshina told Reuters in Rostov, a town 217 kilometers (135 miles) from Moscow.

Voloshina said she was looking for office shelves and tables and also shopping on behalf of a friend from another town. “My heart is breaking,” she added.

Dmitry, another Moscow resident, lamented rapid price rises.

“The watch I wanted to buy now costs around 100,000 rubles, compared to 40,000 around a week ago,” he said, declining to give his surname.

But the spending burst visible this week may peter out.

While there is no palpable sign of panic, the wipe-out of rouble savings and the doubling of interest rates to 20% will squeeze mortgage holders and consumers.

Financial conditions — reflecting availability of credit in the economy — have tightened brutally this year, which Oxford Economics predicted would shrink domestic demand by 11% by year-end and raise unemployment by 1.9 percentage points in 2023.

Zach Witlin, an analyst at Eurasia Group, notes sanctions are already hitting consumers via prices hikes and digital payments disruptions.

While consumers are not directly targeted, “fear and caution are exaggerating the impact,” with the exit of foreign brands such as IKEA creating a “snowball effect,” he added.

IMPORTS TO ISOLATION

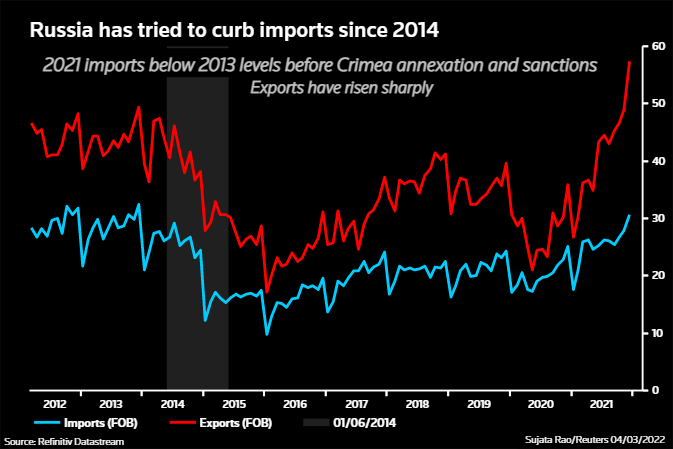

Cars, machinery and car parts comprised nearly half of Russia’s $293 billion imports last year, according to the Federal Customs Service.

The government’s strenuous import cutbacks in recent years mean 2021 imports remained 7% below 2013 levels, before the first sanctions following Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

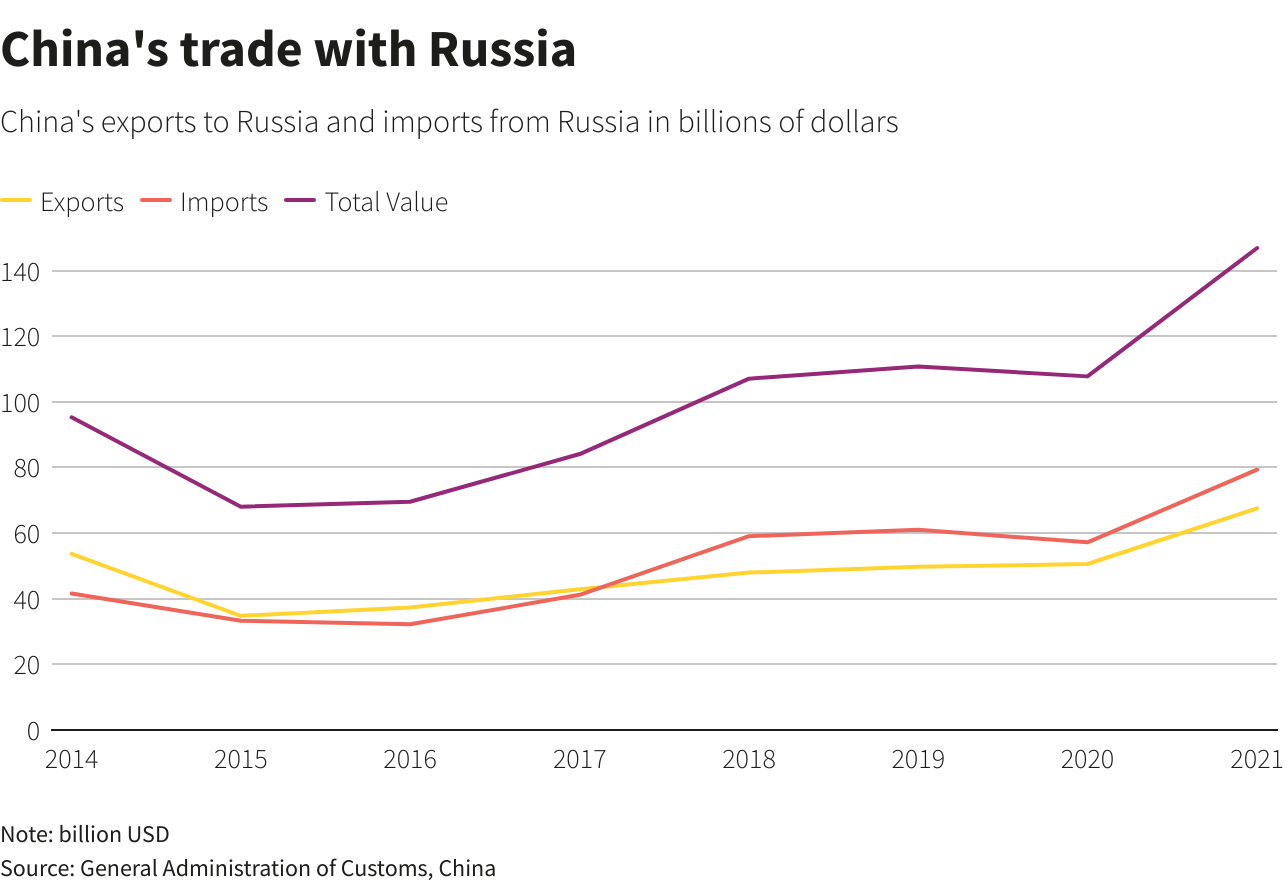

It has also beefed up trade with China, which is the only country to boost exports to Russia since 2014.

But further declines look inevitable as the rouble plunges, insurers refuse cover to businesses exporting to Russia and shippers back away from Russian ports whether to export or to import.

While only a few Russian companies are targeted by sanctions “all of them will feel the chilling effect,” said Matt Townsend, sanctions partner at law firm Allen & Overy. “This is why sanctions are a very effective measure to isolate a country.”

The immediate economic shock will cause a 35% GDP contraction in the second quarter and a 7% decline in 2022, JPMorgan predicted. But “growing political and economic isolation will curtail Russia’s growth potential in years to come,” it added.

That may come about if restrictions “limit the acquisition of technology needed to support Russia’s highest value industries,” RBC Global Asset Management warned.

The Biden administration is preparing rules to curb Moscow’s ability to import smartphones, aircraft parts and auto components.

But multinationals, from tech firms Apple and Microsoft to consumer goods producers Nike and Diageo, have severed links with Russia, meaning shoppers will have limited access to the consumer goods they have grown accustomed to over three decades.

Chinese companies, so far staying put, could grab some market share but they too could fall prey to secondary sanctions as many of their products such as smartphones use U.S. origin technology.

Some Russians are not staying to find out. Lidia, a freelance worker from Rostov said the money transfer curbs were complicating receiving payments from abroad.

“The sanctions have hit me very hard. Prices are already up around 20%…It’s a fact that you already can’t buy some medicines. Things will get worse,” she said.

“Today my family and I are leaving Russia.”