MILLIONS of people with email accounts have undoubtedly encountered fraudulent emails that originate from Nigeria. Online fraudsters from the huge west African nation are also known as Yahoo Boys.

According to data from the Federal Bureau of Investigation analysed in academic research, they have defrauded millions of victims worldwide.

Statistics about the actual value of Yahoo Boys’ scams do not exist. But the wider cost of scams in general in the UK alone has been estimated at £9.3 billion.

Educated Yahoo Boys relied primarily relied on information technology expertise to defraud victims. The value of their scams are much greater than that of uneducated Yahoo Boys who primarily relied on supernatural powers to manipulate victims.

Academic research about Yahoo Boys seems to be gaining traction. But relatively little is known about them. What is clear though, is that they need efficient banking and technological facilities to run their scamming industries.

Consequently, those who live in Nigeria generally live in urban areas where they have established networks and collaborators. Yahoo Boys are predominantly men and boys. Some of them are graduates, students and dropouts from tertiary institutions.

In our recent research, we sought to find out how the fraudsters’ ethnic origin and geographical location influenced their prosecution by Nigeria’s Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC).

We studied how Twitter users responded to the commission’s tweets about the arrest and prosecution of cybercrime suspects.

We argue that the tweets underscored the north-south divide in present-day Nigeria. And that inequalities concerning the arrest and prosecution of cybercrime suspects reflect long-standing disparities in Nigerian society.

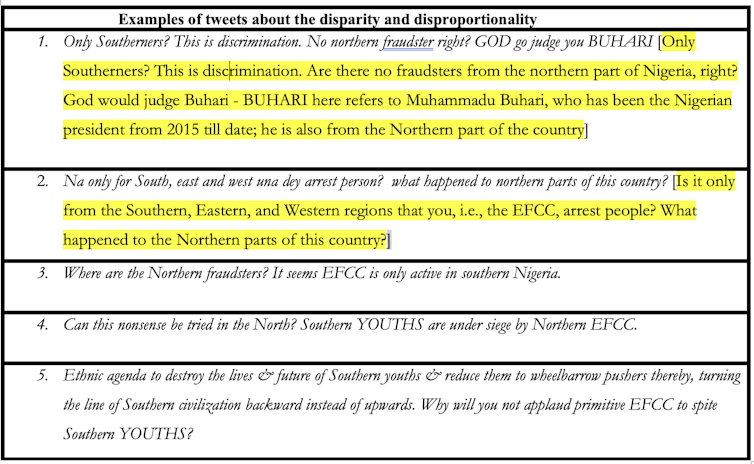

Twitter users’ responses suggest that southerners are significantly more criminalised because the crimes commission is doing selective enforcement of rules.

The crimes commission

The Economic and Financial Crimes Commission is an agency established by the Nigerian government in 2002 to address various kinds of economic crimes and to repair Nigeria’s image. Its primary aim is to stop fraud and corruption – not only by cyber criminals but by public officials too.

The commission generally tweets about its accomplishments in tackling economic crimes. Examples of such tweets include: (a) Two Internet Fraudsters Jailed in Ilorin; (b) Court Jails Fifteen Fraudsters in Enugu; (c) EFCC Arrests Nine Yahoo Boys in Port Harcourt.

We analysed over 100,000 Twitter users’ responses to the tweets. The comments were generally about whether the arrests and prosecutions were fair. We wanted to see what this revealed about the long-standing disparities between the northern and southern regions of Nigeria.

Based on the evidence that came to light on Twitter, arrests and prosecutions of Yahoo Boys from Nigeria’s southern region (like Lagos, Oyo, Edo, Delta, Anambra and Enugu states) differ substantially from the northern region (like Katsina, Jigawa, Yobe, Kano, Borno and Zamfara states).

We deduced this by examining Twitter users’ responses to the tweets by the commission concerning online fraudsters who were arrested and prosecuted from 2019 to 2020 – over a period of 17 months.

The factors responsible

We argue that a number of factors are responsible for the contemporary manifestation of discrepancies between Nigeria’s northern and southern regions when it comes to cyber fraudsters’ arrest, conviction, and sentencing.

First, we argue that fraudsters from northern Nigeria deploy a peculiar modus operandi that does not often come to the attention of the crimes commission and other crime agencies. One is the “hit-and-run method” involving nomadic scammers from northern Nigeria. These fraudulent syndicates usually launch a coordinated attack on an identified viable victim involving spiritual manipulation.

The team travels to the victim’s country, befriends them, defrauds the victim face-to-face, and leaves the country with the money without a direct digital trace to its home nation.

We posit that it’s reasonable to argue that the crimes commission’s disproportionate criminalisation of southern young people may not suggest that these young people are responsible for the bulk of the intercontinental network of frauds originating from Nigeria.

In addition, we also argue that religious and colonial history play a role in the north-south divide in the production and prosecution of cyber crime.

The British authority merged the northern and southern protectorates into a Nigerian colony in 1914, through colonisation. The colonisers introduced Christianity to the colonised, blending it with Western education. However, the British Christianisation of indigenous people was only successful in the south, because Islam dominated the north and resisted Christianity. And many Muslims view Western education with suspicion because of its linkages to Christianity. Consequently, educated populations originate more often from the south than from the north.

And we maintain that regional differences in educational attainment, originating from differing experiences of Christianisation and colonisation, interact with regional disparities in the production of cyber crime.

Nigeria’s more recent economic history also plays a significant role. The Nigerian economy collapsed in the 1980s, resulting in mass graduate unemployment. Unemployment does not cause crime. Nevertheless the graduates and dropouts from the south formed the bulk of the first cohort of high-profile Nigerian fraudsters.

Over time, these layers of graduates produced many fraud templates and became role models. They influenced younger generations from their communities and regions.

Mentees often followed in the footsteps of their mentors, and role models – as set out in this paper titled Birds of a Feather Flock Together. We, therefore, argue that these social conditions meant the younger generation from the southern region became more likely than their northern counterparts to see online scamming as acceptable career paths.

Conclusion

Our article highlighted the value of public expressions on Twitter and legacies of colonisation rarely discussed in cyber crime scholarship.

By doing so, we sought to demonstrate how public opinion on Twitter serves as a lens through which seemingly disconnected factors are organised as related parts of a whole.