GREG MILLS, RICHARD HARPER and MIKE DU TOIT

‘YOU go to the police station,’ menaced Sergeant Silvestre, turning to point behind his back at a lime green building, explaining that the crime was ‘not wearing a mask in the car’.

We were stopped in a queue of trucks and cars negotiating speedbumps, army, police, paramilitary, immigration agents and sellers of nuts, cooldrinks and much else at the bridge that spans the great Save River in Mozambique’s Inhambane Province, just north of the popular tourist destination of Vilanculos.

We saw no tourists at all on the road to Malawi from Maputo, not even adventuresome overlanders and members of the 4×4 brigade. This may have (partly) been down to Covid-19, but their absence was hardly surprising given the levels of intimidation and friction from officialdom.

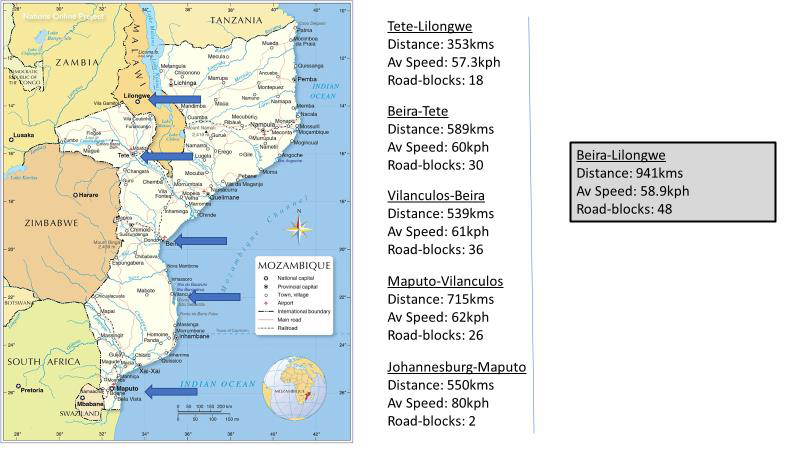

We had set off from Johannesburg two days earlier, a short (and, as it turned out, fast and friction-free) 550 km day’s driving to Maputo.

But the Lebombo/Ressano Garcia border post just a hundred kilometres from Maputo provided an inkling of what was to come. Two stops on the South African side for customs and passports, and not fewer than seven to gain entry into Mozambique. (1)

The road surface progressively deteriorated on the journey northwards from Maputo to Lilongwe via Vilanculos, Beira and Tete.

Despite travelling as fast as safely possible, leaving each day at 0600 to avoid driving in the dark, our average speed scarcely inched above 60 km/h.

At one point, in the 70 kms between Changara and Guro, south of Tete, only a small strip of road was open for 30 km, forcing an informal stop-go arrangement with the occasional game of chicken with the fuel, logging and other trucks which dominate the route.

Save for the very good road between the port of Beira and Chimoio on the corridor with Zimbabwe, the surface followed a predictable pattern – an OK sector for a few kilometres which was followed by disintegration of the road in the dips and around the bridges, and then whole sections where the road, for reasons of age, lack of maintenance, the quality of the original construction, and the extent of rainfall had simply fallen apart into potholes sometimes spanning its entire width.

There were additionally five tolls, costing a total of 220 meticais, including 50 meticais (or $1) for the journey over the Save bridge. The journey over the border to Dedza cost 100 meticais on the Mozambican side for a road pass, and $20 for road tax and $50 for car insurance in Malawi. The woman who removed the bollard at the Malawi border also asked for 4,000 Kwacha, or $5.

And then there was the software, human challenge of Sergeant Silvestre and his ilk.

In the 1,833 km from Maputo to the Malawian border at Dedza, we encountered 97 police and army roadblocks, being stopped at not fewer than 64 of them. Without fail they asked for water, sometimes food.

There were nine speed traps between Maputo and Tete, at which we were stopped twice and forced to pay on-the-spot fines, one for 66 km/h in a 60 zone (I was going 56 according to the GPS), and 82 km/h in a 60 zone again.

With no deregulation signs, it’s virtually impossible to know what the speed limit is.

I suppose that’s the whole idea.

The Sergeant pretended to write down our details on a small piece of paper at Save. As he circled the car continuously tapping on our, by now, rolled-up windows, while his colleagues peered in the back of our Landcruiser, we pretended to ignore him.

Eventually I could take no more, rolled down the window and let rip. He changed tack, rubbing his hand on his tummy while pretending to drink at bottle.

A Red Bull, bottle of water and 200 meticais lighter, we were again on our way, smiles all around.

Aggravation aside, such exchanges add cost and complexity to an already fraught journey littered with broken trucks and road accidents, one of which involving four trucks we only narrowly avoided.

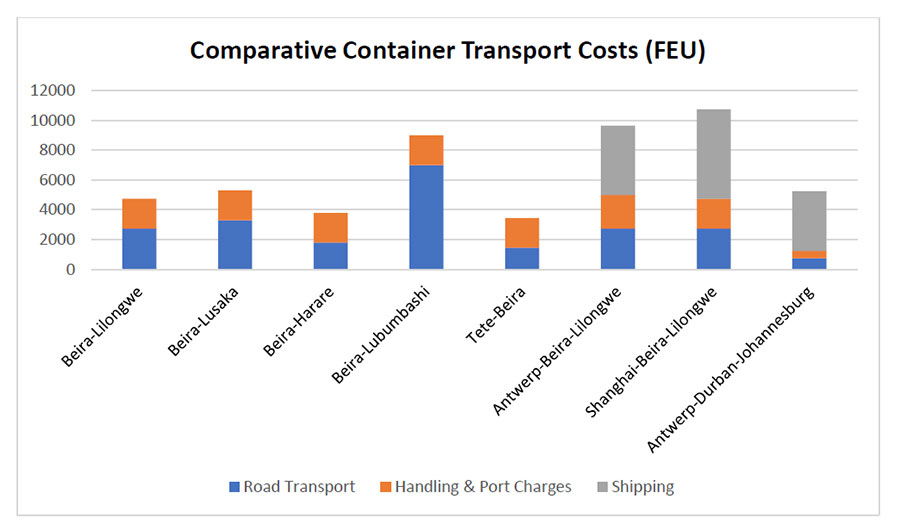

It explains why the cost of moving a (forty foot – or FEU) container to Lilongwe is around $4,750, including port and handling charges totalling $2,000 – nearly ten times the cost through Antwerp for example.

The cost of moving a container through Beira and onto Harare is $3,800, Beira-Lusaka $5,300, and Beira to the Congo a whopping $9,000.

The comparative cost of shipping an FEU the 10,000 km from Shanghai to Beira is $6,000.

Despite the costs, there is clear and rising demand for Beira as an access point, especially for the region, increasing the numbers of containers handled from 34,500 in 2000 to 260,000 in 2019.

Some 85,000 of these were Mozambican exports and imports, the remainder being to and from region, largely Zimbabwe (40,000), Zambia (39,000), Congo (33,000) and Malawi (37,000).

Landlocked Zambia, Malawi and Zimbabwe all depend heavily on accessing port infrastructure in neighbouring Mozambique and elsewhere within their immediate neighbourhood.

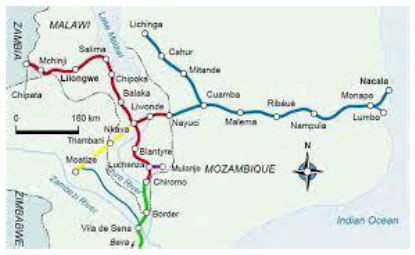

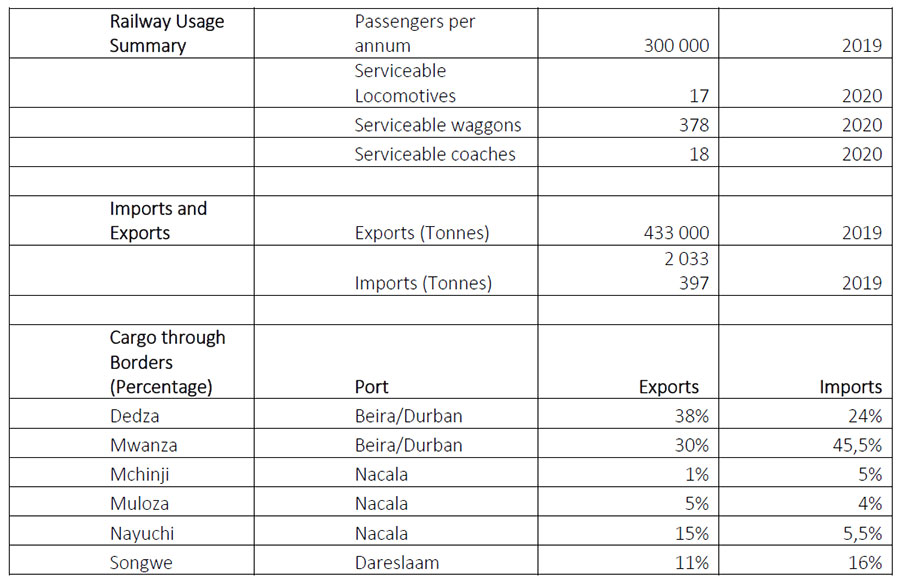

At present, the ratios of volume transported to and from Malawi are 41% by the Beira Corridor (road), 18% by the Nacala Corridor (road and rail), 33% by the Durban Corridor (road) and 8% by the Dar es Salaam Corridor (road).

The port’s efficiencies have improved dramatically, halving dwell time to 10 days between 2010 and 2019, and doubling vessel moves to 600 per day (or 45 per hour).

The top international performer in terms of vessel moves is Yokohama in Japan with 130 per hour, and in Africa Port Tangier with 105. Mombasa is at 47, Abidjan and Durban both at 42, Lome 32 and Cape Town just 29.2

The Search for Solutions

Further improvements are planned to Beira, not least in the organisation of the warehousing, and increasing the customs access points for the thousand or so trucks that traipse in and out each day.

Management believes that these and other changes could double productivity in two years. Since 1998, the port has been run by a private concession.

Until now improvements in the road hardware connecting the port to the hinterland have been piecemeal. Other than the team of labourers uncoiling cabling led by Chinese workers on the bridge over the river Save, we saw two official road maintenance teams en route, each with a small compactor and a smoking pot of bitumen.

There was also one attempt to chip and spray a decayed section, resulting in traffic chaos as the trucks were deviated off the ‘improvements’ by a series of trees laid on the road.

And there was one other, informal road improvement (i.e. pothole filling with earth and stones) ‘toll’.

The potholed and pockmarked passage through the small town of Inhazonia, for example, just off the turn-off from the Beira corridor to Tete, begets the question: why don’t the locals take it upon themselves to fix the roads?

It’s not as if the country lacks a compliant population and the ability to extend control down to the smallest of local levels.

The extraordinary compliance of the population in wearing face masks during Covid-19 is one indicator, as is the fact that the police and army were deployed over such large geography – even if their purpose was mostly extractive rather than facilitatory and inclusive.

Mozambique’s costs and frictions are a high hurdle to opening up the country, with its beautiful vistas and untapped beaches to tourists and investors alike. It is hard to imagine anyone, save a grizzled masochistic veteran, enjoying such a journey. It also makes it very difficult to diversify the economy, and create jobs in the process.

The solution usually proposed in the statist past suggested that the government should provide, or donors.

Either way, the state was to be responsible for ensuring common goods such as roads.

The problem is, however, that the government either does not care enough or lacks the capacity to maintain the roads in a systematic way.

Now the state seems willing to cede a degree of control. The rhetorical solutions to the road conditions now centre on private sector concessions ‘with a reasonable toll’.

Already, however, there is a warning sign in the word ‘reasonable’.

Given the amount of capital required to refurbish such a long section of road, probably some $1,5 billion, the toll would have to be pretty steep, and pretty politically unpopular, not least as it would raise all manner of suspicions about outsiders benefitting from Africa’s poverty.

A ‘Big Bang’ solution would involve a massive reinvestment project with a private sector concession to run and maintain the road funded by tolls.

It would involve turning the Lilongwe-Beira and Beira-Lusaka routes into transport corridors with single entry customs procedures, and expedited vehicle processes at the border posts.

The Brazilian mining firm, Vale, made a (purported) $4.4 billion investment in a coal operation at Moatize, just outside Tete, which included a 910 kms railway (of which 230 kms was new) to link with the northern Mozambican deep-water port at Nacala. (3)

Yet in February 2021, the day before we passed through Tete, Vale announced that it was pulling out of the investment, in part due to high operating costs and in part down to the low price fetched by coal.

The route to Nacala offers one possibly cheaper route to markets, both by road and rail.

The latter means carries currently around 7% of Malawian trade, principally fertiliser which is unloaded at the inland port of Liwonde on the Shire River.

Currently this route carries an average of ten trains per day, six of which are 120 waggon coal trains from Moatize to Nacala (amounting to movements of 20,000 tonnes per day), and four smaller ‘general-purpose cargo’ trains.

There are constraints that will have to be addressed to ensure this link is a viable alternative, not least improvements to the port of Nacala itself, and greater frequency of shipping.

But it is certainly a cheaper option than road: the difference in fertiliser transport costs, for example, being $75 to $40 per tonne.

Another Alternative?

Until now, the focus of successive Malawian governments has been on the rehabilitation of the Beira-Malawi railway from Mchinji in Malawi through Blantyre to Beira, known as the Sena link, of which the rehabilitation of the Malawi section alone is predicted to cost more than $1 billion to carry an estimate of two million tonnes of freight annually. (4)

Yet this is clearly not a bankable solution, even in the long term, the unattractiveness of the high costs no doubt compounded by the political influence of road hauliers on both sides of the border.

Might there be another, lower-cost solution to complement the Nacala Corridor alternative?

Perhaps.

In 2010 the government of President BIngu wa Mutharika completed the basics of a new port on the Shire River at Nsanje, 26 km north of the border at Vilanova Fronteira on the Mozambican side, and Marka in Malawi.

These basics, built at a cost of $20 million (5), consist of a quay and a large concrete slab intended to serve as a river-road transfer point of an eventual $3.9 billion facility.

Nsanje port is non-functioning due to depth and access problems on the Zambezi River in Mozambique.

It was not only badly conceived but was fraught, too, with regional frictions.

At the opening in 2010 the presidents of Zambia and Zimbabwe were invited to the public ceremony to celebrate the planned arrival of a barge carrying 60 tonnes of imported fertiliser.

Mozambican authorities then impounded the barge and detained four Malawians for navigating the river without authorisation.

Mozambique objected to the project on grounds that no economic feasibility study or environmental impact assessment had been carried out. It also claimed that Malawi had not even requested official clearance of the barge.

A feasibility report commissioned by the SADC and published in 2013 concluded that the riverine project was ‘technically feasible but not financially viable.’ (6)

Herein, however, might like the guts of a solution to the road-rail dilemma—which relies on providing a competitive alternative to the effective road monopoly.

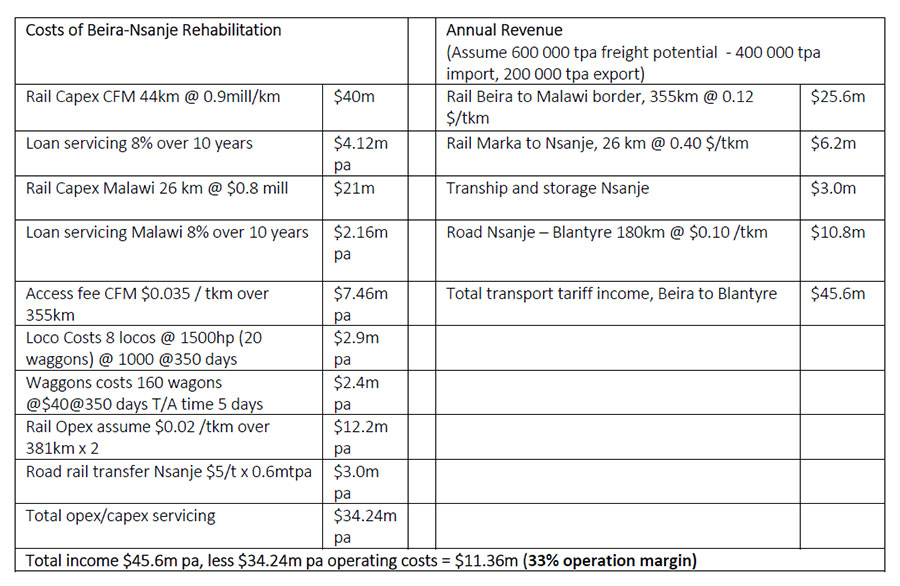

Rather than an expensive rehabilitated link from the Sena line (involving 209 km of rail in Malawi, and 46 km in Mozambique, plus a new bridge at Bangula), the provision of rail access to southern Malawi up to Nsanje, and use of the Nsanje facility as a freight station and customs clearing facility, makes financial and logistical sense.

From there it would involve a switch to road to Blantyre (180 km away). This would utilise 355 km of rail in Mozambique, 26km of rail in Malawi and the remainder via road transport in Malawi, saving 240 km over the Tete road route, and also bypassing the Mwanza and Dedza border posts.

We spent over an hour at the latter, during which time there were no fewer than six steps on the Malawian side alone, and we saw just one truck of more than one hundred waiting actually pass through the barrier.

The costs, centring on the rehabilitation of the 26km link into Malawi, are estimated to be $40 million against a projected operating profit of $11 million per annum.

Assuming an annual freight potential of 600,000 tonnes (400,000 in imports and 200,000 exports) the projected cost savings are $15 per tonne over the Blantyre-Beira road route.

The key objective of this ‘small-but-simple’ approach would be to do away with the road border post processes and delays by running the container imports by rail non-stop into Malawi at Nsanje, where they are cleared, and trucked into various Malawian destinations from there.

The improvement of fertiliser distribution at Liwonde contains myriad benefits for the costs of production in Malawi, and the business and citizens that will prosper as a consequence of the multiplier effects.

Likewise, the improvement of the road and rail networks can assist in spurring regional trade, especially between Malawi and Mozambique, and from Zambia given the ‘natural’ route for its imports and exports both to and from Beira and Nacala via Liwonde, Nakaya, Balaka, Salima, Lilongwe and Chipata.

But trade has to be driven, fundamentally, by business, and that demands putting in place the right policy conditions and ensuring competitive practices.

Transport Needs Business

But spending on new, or rehabilitated hardware is only a fraction of the solution. The solution to the transport dilemma lies in a combination of governance and finance, and leadership.

To be sustainable with a realistic revenue model, growth in economic activity and thereby transport will have to be driven by private sector investment, and that, in turn, has to be facilitated by the government.

Outside of the port of Beira, there are other examples of the transformative power of private capital and expertise.

The investment in Tete’s tobacco industry by Mozambique Leaf Tobacco, a subsidiary of the global Universal group, has been southern Africa’s greatest poverty alleviation story since independence.

It has had nothing to do with government or donors. It may indeed have been successful precisely because it is not dependent on the largesse of any government.

Started in earnest with the opening of a processing plant in 2005, the operation now involves 92,000 smallholders in tobacco production in Tete, Niassa and Zambezia provinces.

Together with the labourers employed (four per hectare farmed), the industry supports over a million people, plus many more indirectly through the circulation of this income in an otherwise poor population.

There are other benefits to the smallholders including the distribution of free maize and soya seed, resulting in annual maize production of 150,000 tonnes, along with support for groundnut and cotton farming.

This has effectively made MLT the largest maize producer in Mozambique even though this is not its core business.

Three-quarters of MLT’s burley tobacco production is from the Tete farmers, a group that would not have, less than a generation earlier, enjoyed this source of income averaging $1,000 per smallholder annually.

Tobacco is now Mozambique’s fourth-largest export after fuels, aluminium and ores, with $230 million in exports in 2019; and top of the agriculture exports, nearly twice as great in income terms as the next largest item in fruit and nuts, followed by oilseeds, sugar and vegetables.

Bolstered by the resuscitation of the nearby coal reserves, the effects on the town of Tete are remarkable.

Where there was little going on just 20 years ago, save some dilapidated Portuguese colonial era factories at the foot of the old bridge named after President Samora Machel, today there are all manner of fresh investments in shopping malls, hotels, petrol stations and some industry to service the mines and tobacco industry. More money has made the town grow.

MLT pushes 3,500 containers up and down the road every year, 80% of the exports going out via the port of Antwerp. The cost of moving a container from Beira to the Belgian city is $1,550 again plus transport, handling and port charges of $3,445.

I was reminded on my journey – you have a long time to think over five days of travelling, plus one waiting around for a Covid test result – that Mozambique in 2021 is the chronological equivalent of Singapore in 2011, the East Asian city-state having received independence effectively in 1965 on the dissolution of the Malay Federation.

There are differences, of course, not least the extent of the geography and the nature of the respective regions, but it does remind how little progress has been made, of the cost of war, and of the relative impotence of donors to enable development.

We stopped off in the villages of Mulambo and Mvala, close to the Malawian border post of Dedza. There we met the MLT ‘farmer of the year’ Atanasio George, 45, and his wife Edita Lorenzo.

They had increased their tobacco yield to 1.6 tonnes per hectare, enabling the duo to purchase a cart, build a house, and buy a herd of cattle. MLT was assisting them with maize seed to improve their food security.

The leaf technician, or extension officer, Edison Lazarus, who arrived on his motorcycle with a solar-powered tablet containing information on the 250 farmers on his watch, spoke about new crop possibilities, including honey and vegetables, the area already known for its fruit and tomato production. Just ten kilometres away, we stopped to speak also to José Charles, also 45, who farmed eight hectares of maize and seven of tobacco, the produce neatly stored in his drying shed.

In less than ten years he had prospered to increasing his land eightfold, also purchasing cattle and admitting, with a broad grin, to ownership now of a motorbike.

The tobacco outgrower scheme enables these farmers to access the global economy, and to profit from it. Extending this to other areas demands prying the dead hand of government from controlling – and smothering – such opportunities, and of course identifying and exploiting these new crops where Mozambique, Malawi and other countries can realise their tremendous agricultural potential.

There is no one single answer to the poverty challenge, no one ‘super crop’ or sudden discovery of minerals. To the contrary.

Improperly managed and fiscally regulated, such finds can destabilise the fiscus and disincentivise diversification not least by raising currency values – what is known as ‘Dutch disease’

Across the range of economic activities bringing down transport and access costs is a critical element to meeting the development and demographic challenge.

Around the town of Madisi, 65 km north of Lilongwe, for example, is a ground-nut seed project promoted by one of the three large tobacco companies.

Such diversification has become imperative as global tobacco demand has fallen, bringing down annual burley production in Malawi from a peak of 210,000 tonnes in 2010 to 90,000 a decade later, during which time the population increased by 25% to nearly 20 milllion.

Groundnuts could be profitable with higher yields, and more profitable with lower transport costs.

The difference between poor seed and antiquated farming techniques equates to 900 kg per hectare versus 2.5 tonnes. But even if one achieves the latter, this amounts to a profit to the farmer of around $750.00 per hectare (or $0.30c per kg).

The cost of moving a container by road south to Johannesburg, a principal market, is $2,800, or $0.14c per kg, and to Antwerp $0.18c, adding a costly premium and taking money out of the farmer’s pocket.

Donors should focus on trying to encourage the sort of liberalisation that prises open market opportunities, and prevents rent-seeking, which adds an, in many instances, unsustainable premium to the cost of doing business.

They, too, can focus on funding key infrastructure, but only if there is a plan to deal with maintenance that does not rely on government.

And they should avoid the sort of expensive supposedly silver-bullet schemes like railways which can only drive the fiscus down a deeper hole.

Conclusion: The Need for a Focus on Software

The answer to Mozambique and Malawi’s railway problems lies not in the construction of new, expensive lines, but getting existing links to work properly.

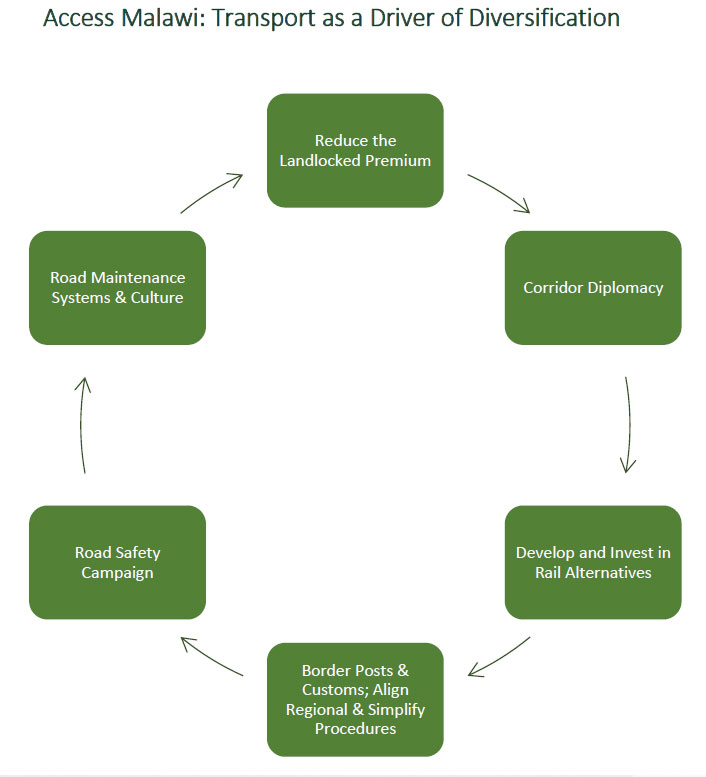

The government should prioritise Access Malawi – an initiative to reduce the premium of transport as a driver of diversification and wealth creation. This should

centre, as the chart above illustrates, on developing rail alternatives to Nacala and Beira, aligning customs systems and procedures across the region as a matter of urgency, simplifying border posts procedures and making these easy to follow, improving road safety and maintenance and instilling a greater sense of regional collaboration and compliance.

Here regional diplomacy is critical. The leaders of both Malawi and Mozambique – and their supporters outside – need to contemplate the contemporary role of borders in Europe when they consider the means to spur regional trade and integration.

Today in Europe these are signified by signs that you flash by at 90 km/h, or more.

In Africa borders remain a place to slow down traffic, to do arbitrage, to extract bribes and ‘help’, and exact a premium of money, hassle and, above all else, uncertainty.

Absent a solution to the state of the roads, and the frictional costs of the man with a gun and a uniform, the prospects of trading to prosperity remains remote.

Endnotes

- This information was gathered during a route diagnostic conducted in February 2021 in the company of Mike du Toit and Richard Harper, covering 2,800kms from Johannesburg to Lilongwe via Maputo, Vilanculos, Beira, and Tete. Additional research trips were conducted to Nsanje and Bangula in the company of Geoffrey Magwede, and to Liwonde with Rod Hagger. Grateful thanks are expressed to all, and to Bo Giersing for his input into the rail section and calculations.

- Information provided by Maersk, May 2020.

- See http://www.vale.com/EN/aboutvale/news/Pages/vale-investe-na-expansao-logistica-de-mocambique.aspx.

- See, for example, https://openjicareport.jica.go.jp/pdf/1000004247_06.pdf.

- See https://clubofmozambique.com/news/nsanje-port-not-a-priority-for-malawi-govt-will-rehabilitate-marka-to-mozambique-railway-chakwera-175013/.

- See https://theconversation.com/malawis-dream-of-a-waterway-to-the-indian-ocean-may-yet-come-true-12471