[tta_listen_btn listen_text=”Audio” pause_text=”Pause” resume_text=”Resume” replay_text=”Replay”]

THE Bapedi have a saying to those not yet born and to be born that Kgaka Kgolo sena Mabala, ha e fofa e nts’o, Mabala a na le Likgakana which means success of a leader is not in herself or himself. Success is seen in their succession.

This Sepedi idiom places the burden of trust on future generations. How those not yet born manage public affairs. My lecture embeds this Kgaka Kgolo philosophy as a principle and hope to guide us in our current as we reflect on our management of public affairs.

For Tsietsi Mashinini was a man of matters of public progress. A man because his youth was stolen, and he aged at meteoric speed. He aged and passed on to the next world leaving a massive impact on South Africa. The question is how do we embrace this impact?

Tsietsi Mashinini would be exactly sixty-six years and five months today, had he not perished in the far lands of Guinea in 1990 at a tender age of thirty-three. Him and his young lions, his student comrades, a number gathered here, a number sleeping the terminal sleep with him gazing over us, mobilized themselves in the most profound of formations, hitherto not witnessed anywhere in the world, where in 1976 at the age of nineteen for Tsietsi, but the average age came to thirteen as the movement engulfed all schools, and Hector Peterson lost his life at only fourteen years old.

Theirs shook the roots of apartheid and not only to reset an irreversible path to freedom but fundamentally accelerated it. They brought an indelible visibility to struggle. They juvenilized an en-mass presence of Black South Africa internationally and mostly densified their presence in the frontline states. To try to establish relevance of why I have been asked to speak today is perhaps of my coming from the Mountain Kingdom of Lesotho which became in good part the epicentre of refuge and an intellectual home for the fleeing youth.

Perhaps it is this line of connection that qualifies me to address this the tenth Annual Tsietsi Mashinini Lecture or is it perhaps my long presence in South Africa and the rare privilege of being the mbongi of secrets of the lives of South African lives. Who we are, how we get born, how we live, work, play and die. The strange phenomena of numbers are that, like Lembede, and Biko before him Mashinini died at the same age as that of Lembed who died in 1947 also aged thirty-three and Biko who was assassinated a year later and perished at the age of 31. Lembede’s comrades who were at the formation of the youth league went on to leave an age up to three times that of Lembede.

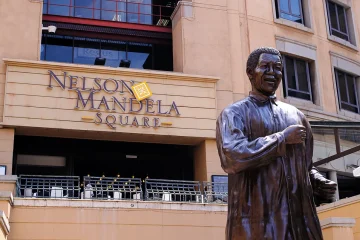

These were Ntate Dan Tloome (1919-1992), Ntate Oliver Tambo (1917-1993), Ntate Ashley P Mda (1916-1993), Ntate Jordan Kush Ngubane (1917-1995), Ntate Walter Sisulu (1912-2003), Ntate David Bopape (1915-2004), ‘M’e Ellen Kuzwayo (1914-2006), ‘M’e Albertina Sisulu (1918-2011), and Ntate Nelson Mandela (1918-2013).

They were able to keep the credo of freedom in our lifetime alive. Their dream that was set in motion in 1944, a year before the end of the Second World War, was waning. The might of the apartheid was at its highest with the historic inauguration of homeland authorities, with the Independence of the TBVC states. Tsietsi Mashinini and his comrades rekindled that hope and ensured that the path to freedom would be shortened to fourteen years. In February 1990 Nelson Mandela was released from prison and political parties were unbanned. It was at this point, in 1990, that Tsietsi rested, his mission was enjoined with that of Lembede in 1944 and freedom in their life time was accomplished.

The question to those of us still alive is what are we doing with the political freedom that those whose life was short but impactful created for us? Let us consider the fact that a militant high school youth of 1976, who undoubtedly rekindled the spirit of overthrowing the colonial-apartheid government would be, on average, 65 years oldies of today. These youth were politically inspired by their creative revolutionary elder counterparts in the universities whose ages would range between 70 and 75 on the average today.

It must be heartbreaking for many of these men and women to look around their townships and villages that were their battlefields and sources of their early education to witness the extent of the social decay that is undergirded by economic exclusion, which ironically intensified following the apparent gain in political inclusiveness after 1994. Did the youth of 1976 drop the ball or was their struggle met with an almost fatal disruption given the persistence of their and their communities’ economic exclusion about 5 decades later?

Has the 1976 youth since been turncoats when followed in the path of the then colonial-apartheid tolerant Bantustan and black urban councillors, whom they regarded as lackeys and outright sellouts? Any memorial lecture about Tsietsi Mashinini cannot possibly be regarded as sound unless it makes an honest attempt to answer these and similar questions. My lecture today is not geared towards any direct answers to these questions. Neither is it deliberately designed to skirt around them.

My attempt to answer these simple but often avoided questions lies in the details of what I have to say.

Introduced in our lexicon immediately after June 1976 was the 1976 generation was a lost generation. Today as we sit and reflect having six decades and more, we look very empty. Give a dog a bad name and hang him. We called the generation of 1976 the lost generation. In the process of seeing the destruction of education, we did not see the rekindling of the spirit and germination of freedom. Through such a lens of rekindling and germination of freedom would arise what do we do to education, to the economy, to health, and to social life. These should be the questions imprinted in our minds as the reality of closure of schools and businesses, the eminent disappearance of the next generation into far-flung lands required a deeper plan, that would pose the question What is it that we the Dikgakana do as beneficiaries of colourfulness that Kgakakgolo bestowed on us.

Thirty-three years after the demise of Mashinini, education in South Africa has deteriorated to levels worse than what Mashinini fought for. The state of our centres of learning has become hotbeds for drugs that destroy the future of children. The culture of teaching and learning has faded fast. Riches and bling have replaced the right thought and empathy that marked the lives of Soweto. In his book, I am a man, Jerry Mofokeng oa Makhetha narrates the life of the sixties in Soweto and how the elders took care of matters. That the shebeen became the centre of learning, and how his mother’s shebeen became a school of life for him. His rendition of the hard life they led shows how Soweto elders were poised for victory over adversity. Leading a purposeful life in a purposeless environment. The class of 1976, led by Tsietsi Mashinini led this purposeful life in a purposeless environment.

But alas, thirty years after his demise the same issues he fought for emerged as the “FEES-MUST-FALL” as the struggle for education continued in 2016. Our education policies lack the needed design that ensures that doors of learning are open. As an illustration, the efficiency and effectiveness index of Black performance relative to White performance at university has deteriorated from a 1:1.2 in the seventies to 1:6 twenty years into democracy and the “FEES-MUST-FALL” movement was an outcome of this deplorable deterioration. The proportions within the population group are such that for every Black graduate there were 1.2 White graduates proportionately in the seventies, and in the current for everyone Black Graduate there are six White Graduates proportionately, and this reflects the rapid deterioration of cohort after cohort of Black entrants into university education.

This is not a reflection that Blacks are stupid but at the centre is the utterly hopeless support system to Blacks once they qualify to enter university. Be it bursary or living conditions at home. This is what Mashinini fought for. We have become a crisis-ridden country. Our memories of the oft repeatedly highlighted triple challenges of unemployment, poverty and inequality have no sooner been now flooded with the replacement of the triple challenges by a new recent triple challenge fad labelled as energy, crime and logistics, all wrought unto ourselves by ourselves and to which a crisis committee has been formed.

The list of lamentable and monumental failures is too long and most crucial and important is that of youth unemployment. The question is what would have Tsietsi Mashinini done when faced with this crisis. Given how the Soweto 1976 was executed it seems Tsietsi and his cohorts understood what Freedom in our Life time required. They therefore planned in detail based on the impact they desired and defined. They knew that their actions would speed up the pace towards freedom and indeed within fourteen years they had brought apartheid to the negotiating table. Political prisoners were released in 1990 and the path to freedom was set culminating in democracy in 1994.

I would plan in detail, but knowing the situation where South African planning systems are back-of-the-envelope calculations, I would implore robust tools of foresight and future proof, that capture the laws of motion of economics and embed them as an arsenal for bringing people together to clearly deliberate on targets required. Fortunately, this exercise has been undertaken already under the Indlulamithi Scenarios – South Africa 2030 through Applied Development Research Solutions which showed that a different path is possible, one that can reduce unemployment, grow the economy and get better outcomes in social cohesion.

But sadly, this is ignored by the government policy regime. Secondly, we have to realize the coal energy systems of electricity excluded the Blacks, the Nuclear Energy systems not only excluded the Blacks but on the eve of democracy, this capability was snatched out of South Africa and the new government also allowed it. To our shores have emerged a new energy system, thanks to one of the class of 1976, a Mojalefa Mofokeng from Ithwathwa. He has been searching and found Dr Professor Maisotsenko whose energy system called M-Cycle as named after Maisotsenko who are bringing this new civilisation. South Africa dare not lose out on this frontier energy based on Tesla that there is free energy in the air. Deploying indirect evaporative cooling to below wet bulb to dew point unleashes freely available energy to the globe. The core difference is that the possibility of this being in South Africa is nigh.

This will change the education system to more empowering, will create the space for new and massified real jobs and jobs of the future. The convergence of this technology that unleashes abundance combined with information technology that has demonstrated that data is non rival ultimately defy the laws of scarcity but unleash the laws of preponderance. Central to these opportunities is real progress in science. Let us remember science needs empathy. Our today’s politics lack empathy. Mashinini led with empathy and that is why his thirty-three years of life have been so impactful. What we need is not the so tired theory of political will. Let us remember those who lack empathy cannot out of nowhere imbue political will. The parent of political will is empathy. Do not expect those who lack this property of empathy to give you what they do not have. Everyone dispenses what they have. They can only grant what they have. Lembede had men and women of principle who imbued empathy and kept the promise alive, Biko imbued empathy and Mashinini exuded empathy. They have all shown that short lives regrettable to us as family and society as this can be does not mean short changed lives. Because in them we can read empathy our politics must be driven by science because it is a subject steeped in empathy. These short-lived stalwarts are the classical Bapedi Kgakakgolo sena mabala. Ha e fofa e nts’o, mabala a na le likgakana. This is Tsietsi Mashinini’s message to us.

· This is an edited version of The Eighth Tsietsi Mashinini Annual Lecture delivered by Dr Pali Lehohla at the Morris Isaacson High School in Soweto. Dr Lehohla is the director of the Economic Modelling Academy, a Professor of Practice at the University of Johannesburg, a Research Associate at Oxford University, a board member of the Institute for Economic Justice at Wits and a distinguished Alumni of the University of Ghana. He is the former Statistician-General of South Africa.