MATHATHA TSEDU

THE magnitude of the October 19, 1977 ban by the apartheid government of newspapers and 19 political organisations reflected both the extent of penetration of the Black Consciousness (BC) philosophy into the communities, as well as an understanding by the government at that time that they were faced with something much bigger and complex.

Bigger because this was a movement that had within the space of four years been able to nationally galvanise university students in 1972 and four years later, high school students in 1976. Complex because this was not a movement begging for a place at the white man’s table, asking to be let in, it was instead talking to black people themselves.

And it was talk based on the understanding that physical liberation has to be preceded by mental and psychological liberation of the oppressed. Or put differently, physical liberation, the removal of chains and obstacles, without the concomitant psychological liberation would be no freedom.

From the basic slogan of “Black is Beautiful” and the fight against skin lightening cream “Ambi”, to “Black Man/Woman you are on Your Own”, BC was working on the mind of the oppressed.

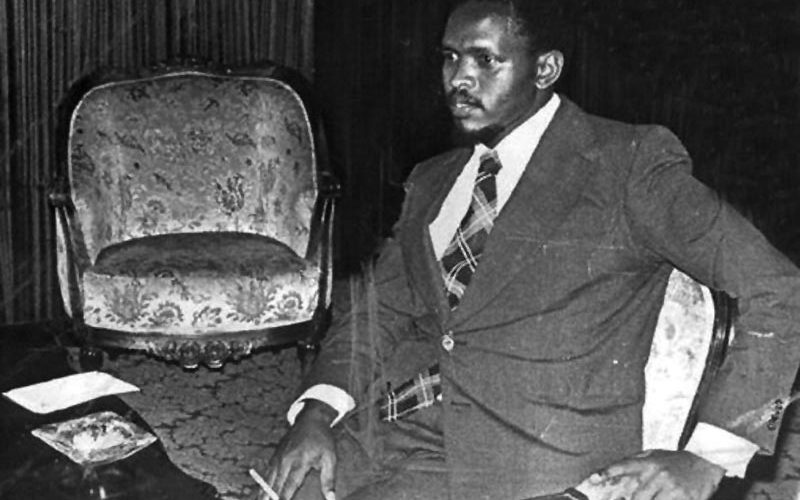

As Steve Biko said: “It becomes more necessary to see the truth as it is if you realise that the only vehicle for change are these people who have lost their personality. The first step therefore is to make the black man come to himself; to pump back life into his empty shell; to infuse him with pride and dignity, to remind him of his complicity in the crime of allowing himself to be misused and therefore letting evil reign supreme in the country of his birth”.

There was no attempt here to try and convince whites of the wrongness of their ways, because for BC, that crime by white people could only be dealt with by a liberated black mind that refused to kowtow. The apartheid government understood this and its potency as they themselves had used internal mobilisation amongst their own against the British, leading to the 1948 victory. So BC had to die. October 19 had to happen.

And amongst the varied factors that were at work on this liberation project, were the media generally and black journalists in particular. The South African Students Organisation (SASO) and the Black Peoples Convention (BPC) understood the role of media in the propagation of the BC ideas. That is why Biko sent Thenjiwe Mthintso to work at Daily Dispatch. That is why this arch proponent of BC was friends with Donald Woods to a point where Woods accepted Mthintso.

That is why Patrick Laurence and the Rand Daily Mail had to eventually be expelled from the SASO Conference at Hamanskraal, outside Pretoria, when they insisted on referring to SASO as a non-white student organisation.

But the key was to win black journalists to the cause and that is why the Union of Black Journalists (UBJ) was formed, precisely on the same basis that SASO came into being. The South African Society of Journalists (SASJ) had deregistered as a trade union to make black membership possible. But it was dominated by white liberals and the crunch came when the then SA flag was put on the table at a conference. Black delegates protested that the flag did not represent their aspirations but the then SASJ president Hennie Serfontein refused to take it down. Black journalists walked out and the UBJ was formed.

The coverage of the national uprisings that’s started in Soweto on June 16 was dominated by black journalists, both because they lived where the story was happening, but also because white reporters were scared to get into townships. 1976 allowed black journalists to set the agenda of the narrative, and helped Percy Qoboza, the Editor of The World, in moving his paper from the scandal, rape murder and soccer only rag into a voice of the youth.

By 1977, Sunday World was running an anniversary series on the uprisings, called “Amandla, The Story of the SSRC” written in the main by Willie Bokala and Duma Ndlovu. But the apartheid government, which we referred to as “the system” was watching and acting.

On September 13 1976, 13 journalists who were covering the uprisings were detained. Amongst them was Joe Thloloe, Mthintso, Bokala, Moffat Zungu, Godwin Mohlomi and Zuluboy Molefe.

Also that month, Don Mattera, who was already banned and only allowed to work as a copy sub editor at The Star, was detained. In December 76, Qoboza was detained briefly. In April 1977, Nat Serache was detained and after an 11-day orgy of torture, skipped the country. In June 1977, Gabu Tugwana was detained, so too was Mthintso, again.

In August 1977, Jimmy Kruger, the so-called Minister of Justice, threatened to ban The World, Qoboza even met Prime Minister John Vorster as a result of the threat. Qoboza was not only an editor but an activist who provided resources of The World for various meetings, including the one that formed the Soweto Committee of Ten in June 1977, chaired by Dr Nthato Motlana and included people such as George Wauchope, Tom Manthata, Mme Ellen Khuzwayo and Lekgau Mathabatha. The Committee of Ten was one of the organisations banned on October 19.

When the Roman Catholic Archbishop, Dennis Hurley issued an order to close the doors of Regina Mundi to political meetings such as commemorations, it was Qoboza who wrote a front-page open letter to Hurley, with the salutation to Your Grace. The ban was lifted.

So in a very real way, The World and Weekend World, unlike the Rand Daily Mail, The Star, Sunday Times and Daily Dispatch which were liberal voices opposing apartheid, the two had become the voice of the nascent revolution.

And if the leaders of the revolution and their organisations were to be decapitated, so too would their voice. It is significant that this 150 member organisation that the UBJ was, was amongst those organisations banned. It was not about numbers but influence.

However, the revolution was not going to be dimmed, just as the UBJ was banned, Writers Association of South Africa (WASA) came into being and later became the Media Workers Association of SA (MWASA). We had planned on the WASA launch in September 1978 in Port Elizabeth but Colonel Piet Goosen, part of the torture team that killed Biko, banned our meeting on the Friday afternoon.

Delegates who were going to Port Elizabeth for the launch had to be rerouted to Verulam, Durban, where Soobrey Govender, had secured a hotel as a venue. We were not going to allow Goosen to determine our fate.

Black journalists were organised and a formidable force in setting the scene, whether by coverage or through our own statements. Every meeting would resolve to call for the release of political prisoners and our own comrades, as most times there would be someone in detention.

When all this didn’t work, they banned the entire MWASA leadership: Zwelakhe Sisulu, Joe Thloloe, Charles Ngcakula, Mono Badela, Subrey Govender, Phil Mtimkhulu, and myself.

Looking at black journalists today, there is no organisation. In fact there is no organisation of journalists at all. With the decimation wrought on the media by both technology and COVID-19, about 700 journalists have been laid off this year alone. Media economics have been turned upside down. And as a result most incisive investigations that are setting the political agenda are driven by donor funded institutions, Most media houses cannot afford to have one or two people away from the daily grind for months on end.

And black journalists have seemingly not been able to crack the donor funds that keep Amabhungane, Bhekisisa, and elements of the Media24 investigative team going. This may have implications politically if most sensitive investigations around political leaders are conducted through external funding.

- This is an address by Mathatha Tsedu at a Black Wednesday Webinar hosted by the Azanian People’s Organisation.