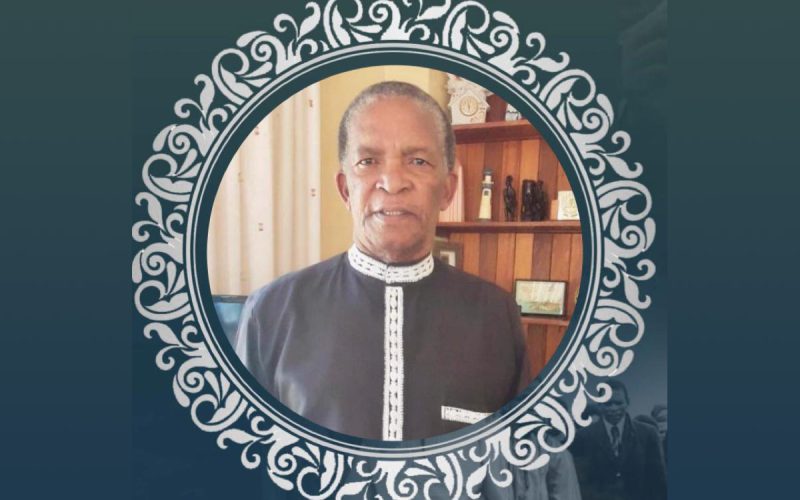

MATHATHA TSEDU

THE picture has become as iconic as the one of the battered face of Steve in the coffin. But this is one of supreme defiance. The scene is Bantu Biko’s funeral on September 25, 1977, in Ginsberg outside King Williamstown. In it, Kenny Hlako(correct) Rachidi, clad in a long gold dashiki and a necklace, stands with a raised clenched right-hand fist, the left hand pulling up the long dashiki.

The fist seems to touch the banner behind him, a banner of the Black People’s Convention (BPC), with its signature emblem of two chained hands with the chain however broken, signifying freedom.

Behind Rachidi is another now late hero of the struggle, Tom Manthata, also in a gold but shorter dashiki, marshalling the cattle pulling the wagon on which Biko’s body travelled to the grave. Behind Manthata and the wagon, one gets a glimpse of part of the huge crowd that had defied security police machinations to limit attendance.

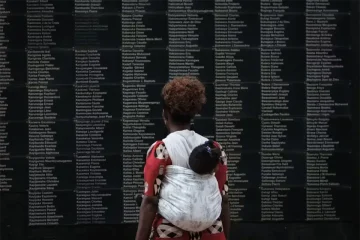

Many thousands others were blocked from attending at roadblocks that were set on all roads leading from anywhere in the country that could take anyone to the eastern cape.

Rachidi, as President of BPC, made it through though and was the natural leader of the procession to lay Biko to rest. He had stepped forward, as he had done many a time before and after, to lead in spite of the dangers of detention and coming home in a coffin, as Mapetla Mohapi, Biko and over 60 others had experienced before.

It is called courage. Courage to believe in the possibility, nay the inevitability, of freedom in the face of the doom and gloom of the death of so many, including at that time Biko. It is also courage to stand for what is right, no matter what.

When 25 days later the regime banned all the organisations standing for freedom and detained hundreds of people without trial for over a year, Hlako was initially left out. He literally challenged the regime to detain him if they thought those he had been leading were wrong because he was their leader.

It did not take long before they obliged and took him to Modder Bee prison where he stayed until his release in 1978. Only to be banned for five years and restricted to the magisterial district of Johannesburg.

Hlako died on Sunday evening (October 23) following a stroke more than a year ago. He had seemed to recover, even taking a long road trip just over a month ago from Johannesburg to Durban with his entire family, only to be flown back when his health deteriorated whilst there.

And with his death, we mourn once again one of those leaders of our struggle who at a very young age took the decision that they would rather die trying to be free than live as slaves in their own country forever.

These were the young intellectual giants that brought Black Consciousness to our shores and our homes, challenging the supremacy of whiteness and insisting instead that Black was not only beautiful but strong too. This was the generation that took on the skin-lightening campaigns behind which lay the notion of white is good and beautiful and black the opposite of both.

Rachidi and Barney Pityana, Ranwedzi Nenngwekhulu, Thenjiwe Mthintso, Saths Cooper, Debs Matshoba, Mohapi, Biko, Motlalepula Kgware, Mthuli ka Shezi, Strini Moodley, Mosibudi Mangena, Mamphela Ramphele, Peter Jones, Pat Machaka, Ben Langa and many others, led the campaign to reject white names and insisted on being called by their black names. The dashiki shirts symbolised an affirmation of the Black identity.

They challenged white Christian hypocrisy and insisted on what was called Black Theology, which held that a God who created Black people to look like Him had to be black Himself. They called into question the white Christ and notions of the meek inheriting the earth as inimical to freedom. This approach to theology was in line with the African Independent Churches that insisted on praying to God in an African way, with drums and dancing.

In doing this Rachidi and his comrades challenged and shook the foundations of white domination like no other organisation or group of people had done before because they aimed at the state of mind of the oppressed. As the leader of the “senior” organisation, BPC, because it was formed to cater for older, senior people, Rachidi epitomised for the system the growth of militant politics from students to workers and adults.

That could not be allowed so the banning of the organisations, the mass detentions and the banning order for Rachidi when he came out of prison. But if they had hoped to cow him down they were wrong. For as soon as the ban expired he joined Azapo and was elected its Southern Transvaal Regional Chair. (Banning orders were never lifted, if they were not re-imposing it, they just let it run out. If on the day it was supposed to end you did not have a fresh one by midnight, you could assume to be free from the ban).

Rachidi’s entry into the militant politics of BC was like many of his age, through religion. He was a member of the University Christian Movement whilst at Fort Hare University. It was at one of these UCM meetings that the idea of forming the South African Students Organisation(SASO) was mooted. Rachidi became a member of SASO and took part in student politics at Fort Hare where he was first suspended in 1966 and later expelled, whilst studying for a Bachelor of Commerce degree.

When seven SASO and BPC leaders were banned in 1973, Rachidi stepped in to lead BPC nationally as National Vice Chairperson. A year later, after the detentions of more leaders following the Viva Frelimo rallies, he held both Deputy Chair and Secretary General of BPC positions. A 1975 BPC congress unanimously elected him President, which was why he was leading Biko’s funeral procession in 1977.

Ever the activist, he held a number of leadership positions in Azapo and also in the Lutheran Church in Soweto.

In his later years, he went back to community development and together with Monelo Bongo, Peter Jones and Pandelani Nefolovhodwe, they created Isbaya, a development non-profit organisation dedicated to advancing rural communities. Isbaya has been doing a lot of training and groundbreaking agricultural work in the eastern cape.

- Kenny Hlako Rachidi was the firstborn son of Manabane and Maria Rachidi at Ga Nchabeleng in Limpopo on April 11 1944. His parents were teachers and he attended various schools, matriculating in 1965 at Sekitla High in Hamanskraal. He was married to Mayttah and they had three children, two sons and a daughter, Palesa, who is herself a prominent activist.