IF South Africans fear that funding political parties is a waste of money, they may care to think about the costs of not funding them. But, if they want value for their cash, the way parties get money needs to change.

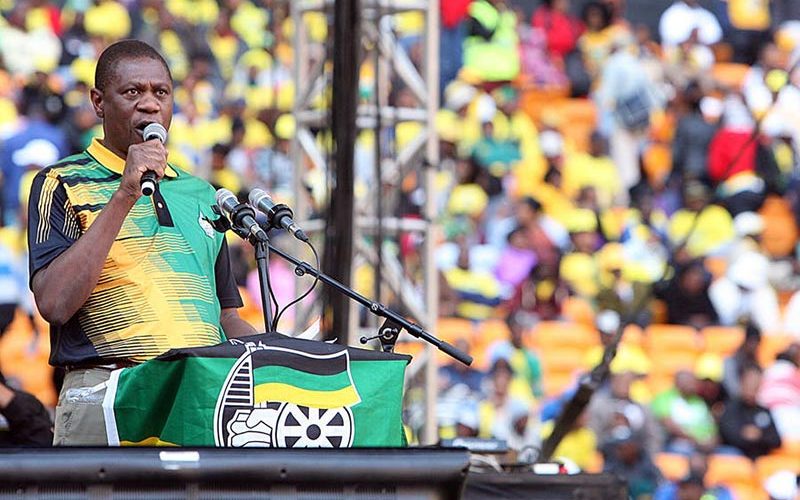

Party funding is back on the agenda in South Africa after the treasurer of the governing African National Congress (ANC), Paul Mashatile, said taxpayers needed to give parties more money. Finance minister Tito Mboweni says he is willing to listen to the argument. Almost inevitably, parts of the media known better for jerking knees than for thought denounced this as a waste.

Mashatile’s reason for asking for more money was interesting. He said that, since Parliament passed a law in January 2019 forcing parties to say who their large funders were, private donors were reluctant to give (despite the fact that the law has yet to take effect).

Usually, big donors love nothing more than to reveal that they have given to a cause – they might hope for a plaque or ceremony. And, if they are giving out of a sense of political commitment, they might be proud for the world to know they are supporting something in which they believe.

If, as Mashatile says, they run for the hills if they believe their identity will be known, it is unlikely that they are giving because they want to help. Their more likely aim is to buy influence.

Buying political influence

When a law forcing parties to say where they got their funds was first floated, it was the official opposition Democratic Alliance (DA) which balked. It said its donors would stop giving if their names were mentioned because they would fear victimisation by the government.

The claim never had much credibility. A government determined to victimise funders of its opponents would have long ago found out who these donors were. It is not likely to victimise them if what it could find out for itself is now on an official form.

It now turns out that it is the governing party, the ANC, not any in opposition, which says its donors are being scared away. This shows that the desire for secrecy is not born of a fear of victimisation but a dread of being found out. The Democratic Alliance is the party of government in the Western Cape province and more than a few municipalities, raising the possibility that its donors wanted secrecy not because they were scared of bullying, but because they did not want the public to know that they were channelling money to parties in local and provincial government.

All this sends a clear message. Private party funding is more often than not an attempt by the moneyed to ensure that government serves them, not voters. While some give because they believe, many donors want to turn democracies into their property.

In South Africa, money has been used to buy political influence for at least two centuries. During the democratic period – since the end of apartheid in 1994 – cash has been repeatedly given to parties and politicians. It is naïve to believe that the purpose is not to ensure that the politicians in government listen to the people who fund them, not those who vote for them.

Since parties always need money – lots of it – forcing them to depend on private money inevitably means throwing them into the hands of donors who will demand favours for their cash. So, South Africans either have generous public funding for parties, or they might as well not bother to vote because whoever they choose will serve not them but whoever has bought them.

Problematic funding model

But, while the ANC is on strong ground when it urges more public funding, its argument is much shakier if it wants that to happen under the rules which now govern funding.

South Africa’s taxpayers already fund parties. A fund managed by the Independent Electoral Commission gives them money in proportion to their last election result.

The first problem with this is that accountability for the funds does not seem strong. There is no point in giving parties public money to ensure that they serve the people unless they are held to account for how they spend it. Since parties can only use the money for specified purposes, they must give the electoral commission annual financial statements to show how they spent it. But no one outside the commission sees these.

In Germany, which Mashatile mentioned as a model, parties do receive generous funding but they must produce detailed, publicly available reports on how the funds are spent so that people can see how their money is being used.

More importantly, perhaps, the formula used in South Africa (and many other countries) is unfair (and happens to favour the ANC). Parties are funded in proportion to their share of the vote at the last elections. The reason seems like common sense: it does not seem right to vote as much money to a party which wins 57% of the vote as one which scrapes only one seat.

But the formula assumes that voters feel the same way now as they did at the last election. They may have changed their mind and most funding may be going to a less popular party. Most important in South Africa is that, since 1994, breakaways from parties (particularly the ANC) have been motors of democratic progress: breakaways from the ANC have reduced its share of the vote since 2009, making politics more competitive and open to voter influence. The formula means a breakaway which took 40% of the party with it would get no funding until after the next election.

Need for change

This argues for a formula which does not reward success at the last elections. There are more than a few ideas on how that could work.

One is that parties get subsidies not in proportion to their votes but to the number of people who support them financially. The size of the donation would not matter – the apple seller who contributes a pittance counts for the same as the mogul who gives a fortune. This would force parties to persuade lots of people to fund them. And it would show how many people cared enough about a party to give it something – anything – to help it get public money. So, it tests current, not past, support.

Another builds on an idea already in the yet to be implemented law. It sets up a fund for multiparty democracy to which private donors can give if they want to support party politics. An independent board would invite parties to apply for these funds. In principle, a similar vehicle could be set up to distribute public money to parties.

These are only two ideas; there are more. But South Africa needs not only more party funding, but a new way of handing it out. – The Conversation.