WHEN hundreds of militiamen arrived in January at a government-run demobilisation camp in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s northeastern province of Ituri, there was a flicker of hope that more than two years of conflict might be abating.

But a few weeks later, the fighters – from a group known as the Cooperative for the Development of Congo, or CODECO – deserted the camp with their children and wives, citing hunger, dismal conditions and broken promises by local authorities.

Now violence is peaking again in a province where more than 1.2 million people have already been displaced by a two-year conflict that has divided communities and revived memories of past wars that rank among Congo’s bloodiest.

Drawn from the region’s marginalised ethnic Lendu community, militiamen have killed hundreds in recent weeks, and forced as many as 200,000 to flee their homes last month alone. Their victims are mostly ethnic Hema, who hold much of Ituri’s economic power.

The recent violence appears linked to the killing last month by the Congolese army of CODECO’s self-described leader Justin Ngudjolo. This triggered an internal power struggle within the group, now scattered across Ituri’s vast countryside.

But the violence also highlights the continued absence of an effective process to disarm fighters in Congo – a problem that stretches back years and far beyond the squalid cantonment site in Ituri – and help them build new lives as civilians. On Monday, one CODECO leader expressed renewed willingness to disarm, although it was unclear if anyone would follow his lead.

UN human rights officials told The New Humanitarian that CODECO’s fragmentation – a process that began last year following disagreements over negotiations with the government – has made it harder to figure out who is in control and who should be held responsible for atrocities.

Aid workers said access to affected communities has been significantly curtailed in recent weeks because of the violence, while camps for internally displaced people and host communities are struggling under the weight of new arrivals.

“They don’t just want us dead. They want some dead and others afraid.”

In January, the UN’s Joint Human Rights Office said the brutal methods used by Lendu militias were designed to inflict lasting trauma on the Hema, forcing them to flee and not return home. Interviews with survivors of recent attacks by TNH paint a similar picture.

“They don’t just want us dead,” said Ephraim Liripa, who fled violence in December. “They want some dead and others afraid.”

TRAGIC: Dieudonné Ngandru Lossi (left) lost his wife when assailants launched a night-time raid on Rho IDP site. The UN has documented a number of similar attacks on displacement camps in recent months. Photo: Alexis Huguet/MSF

Demobilisation blunders

Rich in natural resources, Ituri has been the theatre of some of Congo’s worst fighting. Tens of thousands died between 1999 and 2007 after a power struggle between rebel groups devolved into ethnic violence – much of it between the Hema and Lendu.

After a decade of relative peace, conflict returned in late 2017 when hundreds of mostly Hema civilians were killed in waves of attacks that caught residents off guard and overwhelmed local authorities and aid agencies alike.

Read more → Mystery militia sows fear – and confusion – in Congo’s long-suffering Ituri

CODECO entered talks with the government last September to begin a process known as disarmament, demobilisation, and reintegration, or DDR. The negotiations afforded civilians some rare respite.

But as the process lagged, a group of disaffected CODECO fighters formed a splinter group known locally as Sambaza, or ‘to scatter’ in Kiswahili – and violence against civilians resumed.

Among the remaining combatants, several hundred entered a run-down transit centre with their families in a village called Kpandroma in early January – but left a few weeks later carrying the same weapons they arrived with.

“Terrible” conditions and food shortages were to blame for them leaving, said Xavier Kisembo, the director of Justice Plus, an Ituri-based rights group. Others said fighters resented perks given to another Ituri armed group undergoing demobilisation, the FRPI.

Similar problems have plagued past DDR initiatives in Congo, with many combatants failing to complete the process, and some dying of starvation and disease while waiting. Dissatisfied with civilian life, or spurred into action by new conflicts, those who do disarm often remobilise.

Provincial governors recently launched a new DDR initiative – the national programme fizzled away as international donors pulled out – but a common framework is needed to steer efforts, UN officials said, as is central government funding, clearly lacking at sites like Kpandroma.

“The provinces don’t have the resources,” said El Hadj Bara Dieng, who is in charge of DDR for the UN’s peacekeeping mission in Congo, MONUSCO. “Even for them to pay their own salaries is sometimes difficult.”

‘HOME’: An aerial view of an IDP camp in Drodro village, where thousands of people are living. An estimated 1.4 million people have been displaced by conflict in Ituri. Photo: Alexis Huguet/MSF

Access denied

With efforts to disarm CODECO failing, five residents who spoke to TNH over the phone described terrifying attacks. Lipara, a father of seven, said one of his sons was burnt alive and neighbours killed with machetes and machine guns. A man in his 20s who asked not to be named described seeing corpses with body parts mutilated.

The Congolese military points to the killing of Ngudjolo as evidence of sucess, but civil society groups told TNH that Lendu civilians are being arbitrarily accused of militia involvement by soliders, while the UN has documented extrajudicial executions, rape, and forced labour. Hema community leaders said they don’t feel protected either.

“Year by year our people fall dead while the soldiers look on,” said John Nduru, a Hema leader.

Though aid groups have received alerts suggesting more than 200,000 people have fled their homes in recent weeks, insecurity has prevented them from going out and corroborating the number. Other aid programmes have also been suspended as CODECO fragments and launches revenge attacks.

“There’s increased risks of [aid groups] simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time,” said Alex Wade, head of mission in Congo for Médecins Sans Frontières.

Most displaced people have moved to host communities, but thousands have spilled into camps already full to bursting. Communal hangers and tents have been erected in some of the largest sites in Bunia, Ituri’s main town, but there’s no land left to expand into and many new arrivals have been forced to squeeze into shelters that are already occupied.

Even before the latest wave, Ituri’s camps failed to meet basic humanitarian standards, Wade said, with too few latrines and water points. The cramped, unsanitary conditions fuelled a measles epidemic that left dozens of children dead last year. As COVID-19 closes in, there are fears it could prove deadly again.

Shrinking humanitarian access – particularly in the hotspot of Djugu – has prevented the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, from distributing soap to some camps to help prepare for the coronavirus, while Wade said he fears continued instability could thwart efforts to construct COVID-19 wards in hospitals MSF is supporting.

Most aid agencies said funding remains insufficient to address problems. One NGO in Bunia recently ran out of money to pay a contractor to take away sewage from a camp hosting thousands of people. For weeks, faeces was left flowing over the top of squalid pit latrines.

“Ebola was a priority for almost two years,” said Wade. “Now we’ll see how [COVID-19] affects the funding priorities.”

Mystery militia

While much is still unknown about the Lendu militias – for example, who helped them acquire weapons and the capacity to coordinate attacks – residents and rights groups say the conflict is occuring in the shadow of past ones.

Colonial administrators armed with racial theories viewed the Hema as a “superior” group and helped them into positions of privilege in education, administration, and business. Land laws introduced by Mobutu Sese Seko – Congo’s former leader – entrenched Lendu marginalisation.

Foreign interventions by neighbouring states inflamed local conflicts and drove young men into the hands of rebel groups. Some Lendu fighters who later demobilised may have picked up weapons again in 2017, with much the same grievances and few fond memories of civilian life.

Two notorious warlords from Ituri’s past – Germain Katanga of the mostly Lendu FRPI, and Thomas Lubanga of the largely Hema UPC – have re-emerged in recent weeks, after serving prison sentences issued by the International Criminal Court.

Lubanga’s release triggered celebrations among some Hema in Ituri, compounding fears that the community – and other ethnic groups targeted by CODECO – may choose to pick up arms. So far they have steered away from organised violence in what has been a largely one-sided conflict.

“This is what is worrying for everyone,” said Abdoul Aziz Thioye, the UN’s top human rights official in Congo. “The risk to see the Alur and the Hema create self-defence groups to protect themselves.”

VICTIM: A six-year-old girl was shot in the shoulder during an armed attack on an IDP camp last September. Photo: Alexis Huguet/MSF

No refuge

Last year, given that CODECO appeared organised enough to be considered an armed group with responsibility to respect international humanitarian law, the UN concluded that militia attacks in Ituri could constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity.

But it is harder to assign blame to a fragmented group with no clear central command structure, said Thioye. His office is now investigating five militia factions and has swapped CODECO in its communications for the more ambiguous sounding “Djugu-based assailants”.

“From a human rights perspective, it’s very difficult.” Thioye said. “You need to have a clear vision on attribution – who does what.”

Despite the splits, the modus operandi of the fighters has remained largely the same, according to testimonies from survivors: targeting civilians with a cruelty designed to inflict more than just physical wounds.

As well as attacking villages, militiamen have targeted displaced people who attempt to go back home, darkening the prospect of large-scale returns any time soon, said Lena Becker, a reporting officer based in Ituri for UNHCR.

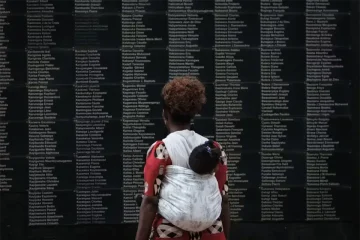

Safety is also far from guaranteed for those stuck in ramshackle camps, with the UN documenting a string of night-time militia incursions on IDP sites that have left scores dead.

Ephraim Liripa, who is now living in a camp just outside Bunia, said residents are living in daily “terror” that the militia will come back for them. Hunger, he added, is the only thing helping them forget.

“We can’t return home,” he said. “I don’t think our lives will ever be the same.” – The New Humanitarian.

- At a glance: The violence in Ituri

- Reports of 200,000 displaced in April; 1.4 million uprooted overall.

- Aid groups lose access to affected communities as violence rises.

- Splits in rebel ranks, the assassination of militia leader and failed disarmament process drive the latest violence.

- Unsanitary conditions at camps a worry as COVID-19 closes in.

- Militia group targeting displacement camps and people returning home.