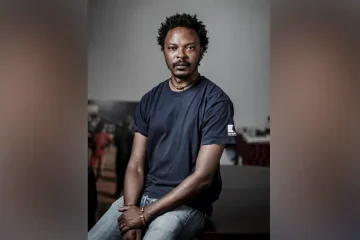

JAMAINE KRIGE

“I see them as twins and I love them both,” Constable Lucky Matome laughs as he describes juggling his two lives; one, a kwaito music artist, the other that of a policeman in the South African Police Service.

“When you have twins you cannot say one is more beautiful than the other, because they are different but identical, and they are both your children. Like twins, I must treat them equally and give them equal attention, so that one does not suffer because of the other,” he said.

His police work is important and it allows him to make a difference. But it is music that feeds his soul.

Maintaining this balance is no mean feat but Matome has risen to the challenge. As much as he has raked in local and national music nominations, he has also received numerous awards and accolades for his work as a policeman. “If my police work is affected by my other life, I will suffer because I won’t be able to provide for my family, but if my music gets neglected I will be suffering spiritually and emotionally because it is my first love,” he smiles.

Is there a difference between the man, the police officer and the performer? He shakes his head. “That’s like trying to remove the milk from the tea,” he laughs. Matome is a man who laughs often. “Once the two are mixed, you can’t separate them again.” The only real difference, he says, is the way he impacts the world in his two different roles.

“When I am Constable Lucky Matome, I’m a police officer that seeks to address issues that affect the safety and security of my community and my country. My mandate then is to serve and protect.”

His mandate as a musician, however, is slightly different. “When I’m Scylash, then my aim is to feed your soul when I perform for you, and to speak to and bring out the best parts of you through my music.”

Both mandates are important, he says, and his work as a police officer often feeds into the music he makes, which tackles a variety of social ills and brings across a strong message of social responsibility. His chosen career influences his art, because he draws inspiration from the situations he encounters every day. “I try to address issues that affect the people I meet on a daily basis and I sing about the things I know about.”

Matome’s police career started more than two decades ago. He remembers the moment when, as a teenager, he first realised he wanted to be a cop. He was on his way home from school when a man armed with a knife demanded his possessions. He was terrified.

“Afterwards, I was sitting at home and I started thinking that if the police had just been around, I could’ve been safe and my stuff would still be with me now.” He knew he wanted to ensure that other people in his community did not suffer the same fate and when he left school, he signed up as a police reservist. By 2010 law enforcement was his full-time career.

He laughs when he recalls how years after the encounter that set him on the path of becoming an award-winning police officer, he had a run in with the man who had held him up as a teenager. “He didn’t even remember me or recognise me, but I told him I was one of the boys he robbed a long time ago, and I arrested him for drinking in public,” Matome laughs. “It’s funny, but seeing him again helped me to heal, and reminded me how important it is to have a heart for people who have been victims of crime, because I had been through that myself.”

While his passion for police work was sparked in his teens, his love for music started long before that. “I started dancing when I was still in my mother’s womb,” he says, and his body starts to sway to an invisible beat as he speaks. Everything he says and does is rhythmic. He remembers attending gatherings at his aunt’s house as a child, where the women would come together for a stokvel. There was always music.

South Africa is a musical place, and he says no genre better represents the spirit of South Africa than kwaito. “When you say kwaito, people immediately think of places like Soweto, Sophiatown, Kagiso and Munsieville,” he ticks off the music hubs where the genre was born at the start of South Africa’s democracy in the early 1990s. “Times were hard back then, and the only time when people would gather and enjoy themselves was when listening to music – kwaito or kofifi music, marabi music and the beats of our people. That’s why I was drawn in,” Matome explains. “That’s how I was hooked.”

During South Africa’s apartheid years, music was often an act of defiance and of protest, but it was also a form of nourishment, self-love and an attempt to reclaim a narrative previously removed from the people who lived it. This was especially true in the early 1990s, as the South African landscape started shifting from one of oppression, censorship and sanctions to incorporate a newfound freedom of expression. Suddenly, young artists had exposure to previously inaccessible continental and global artists. Suddenly, South African musicians could reclaim a role on the global stage. Kwaito soon became the ultimate expression of these freedoms.

He falls silent for a moment, and when he speaks again his voice is softer than before. “Kwaito is us. Kwaito is black. Kwaito is South African. We sing it in our language and the beat is us and the vibe is us.” This, he believes, is how to influence the world. “We can use music to address some of the issues in our social and political landscapes on the continent, and in doing so we can build a better Africa,” he says. But why stop at Africa? “If we use music to address the issues that affect us as human beings, nationally and continentally and globally, then we can build a better world.”

South Africa’s viral gospel-influenced house song Jerusalema by Master KG and Nomcebo is a good example of how music can unite people. “That song was not even nominated for a South African music award, but it became the world’s anthem in 2020!” It was a song, he says, that brought people together, across borders and oceans. “And you don’t have to understand the lyrics, because as long as the melody and rhythm speak to your soul and find its way into your bloodstream, then music is a universal language.”

Nothing is permanent, he says, but music can be. “We are just passing through this world, but if we make good music that is sustainable then that will be the lessons and the legacy we leave for our children, and for our great-grandchildren and their children,” he smiles.

He has since infused his music with the increasingly popular amapiano sound, a hybrid genre of house music that emerged in South Africa less than a decade ago that draws heavily on the music styles of deep house, kwaito, jazz and lounge music. “The continent is really enjoying the sound, and the world is really enjoying the sound,” he says. He says amapiano has taken off globally, which is a good indication of the beat that South Africans bring.

His latest release, De Bozzer Reload, is gaining traction outside of South Africa, with increasing streams and airplay from Zimbabwe, Botswana and Zambia. His most confusing continental hit, however, is a song that he released a few years ago titled Zamalek, which shot to success in Egypt. “I was so surprised one day when I checked online and checked my radio monitor and saw how good it was doing there,” he laughs. Zamalek is the colloquial name for Carling’s Black Label beer in South Africa, but is also the name of a region and a popular football club in Egypt. This, he says, must be how Egyptians discovered his music. Regardless of how they found him, he added a number of Egyptians to his fan base going forward. “Maybe I need to explore what about that song made the people of Egypt like it so much!”

Matome says the support from his music fans and from his colleagues has been overwhelming and maintains he is blessed with bosses who understand the need for creative expression to deal with the harsh realities of the job. “The South African Police Service as an organisation allows people to express themselves because it’s an environment that sometimes can be traumatic,” he explains. “They know how important it is to find creative ways to unleash that stress, unleash the trauma and be able to perform your duties accordingly, so they have always allowed me to do my music so that I can express myself.”