EGYPT’S state-appointed human rights council has urged prosecutors to investigate whether an economic researcher who authorities say died after being interned in a psychiatric hospital was a victim of forced disappearance.

The National Council for Human Rights (NCHR) also said in a statement posted late on Monday that it was awaiting the result of an autopsy of the economist, Ayman Hadhoud, to see if he was subjected to torture before his death.

Forced disappearance is a term activists use for detentions carried out by security agencies during which lawyers and relatives are not officially informed about the whereabouts of detainees or the charges against them. Authorities deny that they take place.

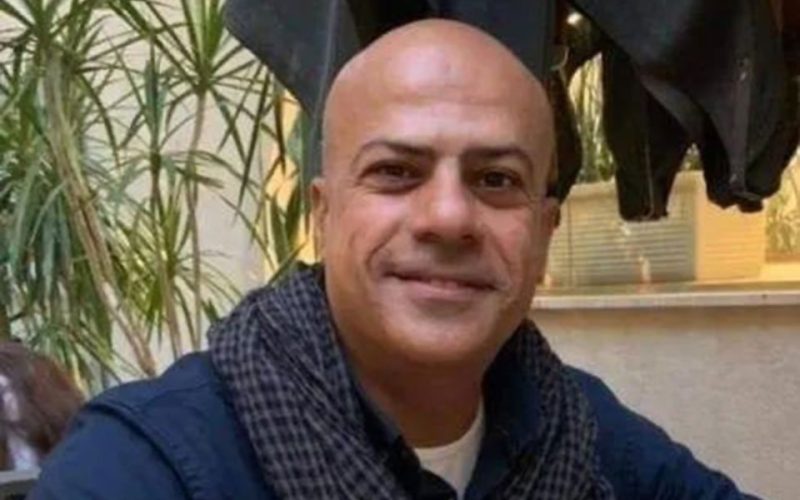

Hadhoud was a freelance economic expert in his late 40s and a member of the Reform and Development Party, a liberal party with a small presence in parliament. Its leader, Mohamed Anwar al-Sadat, sits on the NCHR and has mediated some recent prisoner releases.

Egypt’s public prosecution said in a statement that police arrested Hadhoud on Feb. 6 after a guard found him trying to enter an apartment in Cairo’s Zamalek neighbourhood, and that prosecutors sent him to a mental health hospital after judging him “incomprehensible” during interrogation.

An interior ministry statement said he was arrested over a break-in and sent to the hospital after questioning. Egypt’s state information service gave no immediate comment on the case.

The prosecution said it was notified of Hadhoud’s death from cardiac arrest on March 5.

A lawyer for Hadhoud’s brother Omar, Fatma Serag, said the family were only informed about the death on April 9. They had concerns and doubts about the reason for his detention and his whereabouts afterwards, and the delay in announcing his death, she said.

Two security sources, speaking on condition of anonymity, said Hadhoud had been detained in February on accusations of spreading false news, disturbing the public peace, and joining a banned group – generally, a reference to the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood and a charge often levelled at political dissidents and activists.

Omar Hadhoud told prosecutors on Tuesday that his brother faced no such accusations and had no history of mental illness, Serag said.

There has been a far-reaching crackdown on political dissent in Egypt since then-army chief Abdel Fattah al-Sisi led the overthrow of democratically elected president Mohamed Mursi of the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013.

Rights groups say tens of thousands of Islamists and liberal dissidents have been detained over recent years and many have been denied due process or been subjected to abuse or poor prison conditions. Officials say security measures were needed to stabilise Egypt, deny the existence of political prisoners, and assert that the judiciary is independent.

The NCHR said it was coordinating with the public prosecution and interior ministry over 19 complaints it had received about alleged cases of forced disappearance since it was reconstituted late last year, as well as complaints about extended pre-trial detention and inhumane treatment in prisons.

The revival of the NCHR, which had been in abeyance for several years, is one of a series of steps Egyptian authorities have taken in recent months in what they say is an effort to address human rights. Critics have dismissed those efforts as hollow.