REELING from South Africa’s worst-ever electricity crisis, local authorities across the country are turning to private suppliers to help businesses and households keep the lights on.

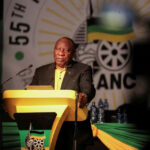

President Cyril Ramaphosa has declared a state of disaster over the energy crunch, which is seen wiping as much as 2 percentage points off economic growth this year.

With South Africans spending up to 10 hours a day without electricity due to rolling blackouts by struggling state utility Eskom, the tourist city of Cape Town aims to halve power cuts for its residents by 2026, its executive director for energy Kadri Nassiep said.

Officials plan to procure up to 500 megawatts (MW) from private power companies by 2026 to provide roughly a third of the city’s annual 1,500-1,800 megawatts (MW) electricity needs.

They are also looking at offering households monetary incentives to save power during peak demand.

“Our idea is to make up the shortfall that Eskom is not able to provide so that we can get the economy growing here again, investors interested again, get jobs back,” Cape Town mayor Geordin Hill-Lewis told Reuters.

Debt-laden Eskom said earlier this month that it was only able to supply 56.6% of the power needed nationally in the 2022/23 financial year.

The electricity crunch has been years in the making, a product of factors including delays in building new coal-fired power stations and easing regulation to enable renewable energy producers to swiftly bring projects onstream.

INDEPENDENCE FROM ESKOM?

Cape Town’s Nassiep said the city was taking steps towards total energy independence from Eskom beyond 2030.

It issued a 200-MW solar energy tender last year and expects to follow that up with another for up to 300 MW of battery storage in the next few weeks.

Other cities including Johannesburg are looking at issuing similar tenders though unstable political coalitions have delayed their finalisation.

Johannesburg’s bulk energy supplier, City Power, in November requested proposals from private companies for an up to 36-month purchasing agreement and hopes to add 500 MW to the city’s grid, then mayor Mpho Phalatse announced in January.

The neighbouring Ekurhuleni municipality has signed deals with 46 private power companies for 700 MW, according to its 2020/2021 annual report.

Hill-Lewis said Cape Town also plans to change its energy policy to allow households and businesses that produce solar power to sell the excess to the city.

There are some challenges.

It is mostly big businesses and wealthy residents who can afford to install solar panels, which can retail between 60,000 rand ($3,372) and 250,000 rand. In Cape Town, for those wanting to sell excess power to the city, a 12,000 rand feed-in meter is required.

“As a small business, we cannot afford to put in solar panels. We work hand to mouth,” said Faieza Caswell, a seamstress in Cape Town’s Mitchells Plain township.

There are also large residential areas that, due to the historical make-up of the city, have little option but to buy electricity directly from Eskom so risk being left out.