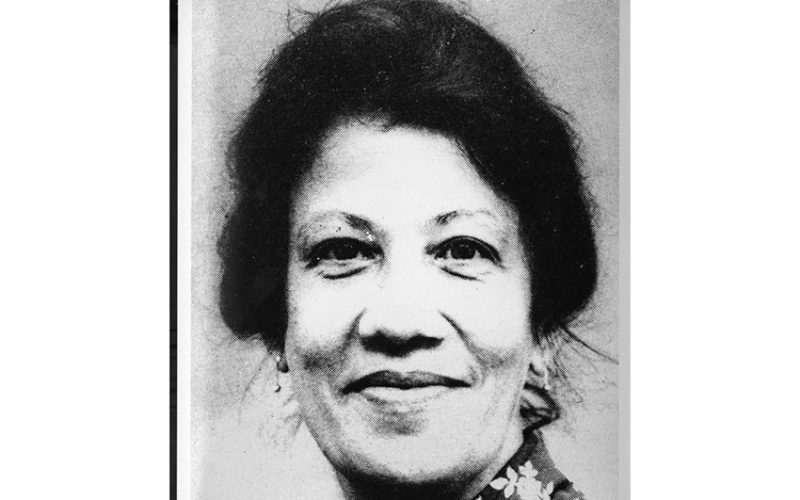

ON the morning of 29 March 1988, Dulcie September, the 52-year-old representative of the ANC for France, Luxembourg and Switzerland, was killed by five bullets fired at point blank range from a .22-calibre pistol fitted with a silencer. She died outside the door of the ANC offices on the fourth floor of the building located at 28 Rue des Petites-Écuries in Paris.

September’s death sparked international outrage, particularly in France, where tens of thousands of people lined the streets of the capital for her funeral on 9 April 1988. Almost immediately following what would prove to be the most high-profile assassination of an ANC representative on foreign soil in the apartheid era, rumours began to circulate that it was the work of agents of the South African state.

Over the past three decades, many investigations by French and South African authorities, journalists and authors have created a fog of mystery and conspiracy theories that continue to surround her death. These investigations have helped to turn the woman at their centre more into a name and symbol of the struggle than a human being who may have asked the wrong questions at the wrong time, and paid the ultimate price for it.

As the 33rd anniversary of her murder approaches, a new documentary titled Murder in Paris tries to pull together many of the complicated and frustratingly inconclusive searches for a smoking gun in the mystery of who killed September, while also reminding audiences of who she was and where she came from.

Directed by award-winning filmmaker Enver Samuel, who made a documentary about the long quest for justice of Ahmed Timol’s family and the historic reopening of the inquest into his death in 2018, this film is very much a work of activism. It seeks not only to restart a conversation about September’s murder, but also to inspire a recommitment to her legacy as a fighter for democratic rights and the rights of women in a South Africa she never lived to see realised.

Lawyers for the September family in France have already included Murder in Paris in evidence they submitted to the French government in February as part of a petition to reopen the investigation into her murder.

A life of activism

September was born in Gleemore in Athlone on the Cape Flats in 1935. While training as a teacher, she became politically active and founded the Yu Chi Chan Club, a militant reading group that included Kenneth Abrahams and Neville Alexander. In 1963, the club became the National Liberation Front, an anti-apartheid organisation ideologically committed to armed resistance against the apartheid government.

September was arrested in 1963 and charged, along with nine others, with conspiracy to commit sabotage against the state. She was imprisoned in 1964, serving five years, and upon her release was slapped with a five-year banning order. In 1973, she applied for and was granted a one-way permit to leave South Africa. She went to Europe, where she became actively involved in the anti-apartheid movement and joined the ANC in 1976. Working for the ANC and its women’s league in various capacities both in London and Lusaka, she took up her position in France in 1983.

In the decades since her death, the theory that September was murdered by agents of the apartheid regime has been probed with varying degrees of success. For his 1997 book, Into the Heart of Darkness,the now controversial journalist Jacques Pauw interviewed playboy arms dealer and self-confessed apartheid spy Dirk Stoffberg, who claimed that he had been part of a state-sanctioned plan to kill September. His task had been to hire French assassins. Stoffberg was murdered with his wife at their Hartbeespoort home in 1994, taking his secrets with him.

A French government investigation into September’s killing did not name her assassins, but it placed her killing within the context of a broader plan by the apartheid state to eliminate senior ANC figures in Europe. An investigation by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997 also proved inconclusive in terms of who was responsible for pulling the trigger of the pistol that killed her.

In his book Apartheid Guns and Money, published in 2017, author Hennie van Vuuren revealed that newly obtained archive documents showed that at the time of her killing, September may have been asking too many questions about the relationship between Armscor and French arms dealers. This would have made her a target for “two probable instigators: South African security services and French intelligence”, Van Vuuren wrote.

As Apartheid Guns and Money has shown, the South African embassy in Paris was home to more than 30 Armscor officials who were engaged in significant sanctions-busting deals with European arms companies. This was a closely guarded secret for over three decades and the theory was expanded upon in a 2019 podcast series, They Killed Dulcie, which was produced by Sound Africa in collaboration with Van Vuuren and the non-profit organisation Open Secrets, of which he is the director. If Dulcie September had uncovered these facts she would almost certainly have been a target.

Basis for documentary

In 2018, Dutch investigative journalist and former anti-apartheid activist Evelyn Groenink published her book Incorruptible, in which she concluded that September had also been close to exposing evidence of top-secret nuclear weapons cooperation between the French government and the apartheid regime. This had probably earmarked her for assassination, wrote Groenink, whose decades-long investigation into the murder serves as the major vehicle for the documentary’s examination of the mystery.

Delivering the 2009 Ruth First Memorial Lecture, Maggie Davey, the head of Jacana Media publishers, told the story of what happened to her and her staff when they attempted unsuccessfully to publish Groenink’s book in the early 2000s. They were threatened with physical violence, legal action and the potential destruction of the business.

Despite winning a court case and facing off the threats, ultimately the publisher felt that “the entire project soaked up more money and resources than a small publisher could afford. We decided not to go ahead with the publication… It was a painful and disquieting decision to take,” said Davey. Groenink finally managed to publish her book privately.

Samuel says that prior to being approached by members of the September family in 2017 to make a film about her, his knowledge of September “was pretty weak… I knew about [her] and the killing, but I didn’t know much. It was vague in my memory about the assassination but I didn’t know much about her.”

After immersing himself in the mountains of articles, books and reports about investigations into September’s death, Samuel interviewed Groenink and “got her buy-in, [which] helped the film to become something that not only told Dulcie’s story, [but also] told the story of Evelyn’s quest to find out who the killers were… The pairing of Evelyn and Dulcie was very strategic and I thought it would be interesting to tell it through Evelyn’s point of view in terms of unfolding the mystery.”

Jumping in

While working on a reality television series in 2018, Samuel heard that there would be a week-long programme of events to commemorate the 30th anniversary of September’s death. Like much of the memorialisation of the former ANC activist, these celebrations did not take place in her native South Africa but on the streets of the city where she was murdered. Samuel quit his contract with the reality show, borrowed money against his home loan and funded himself and a skeleton crew to cover the events in Paris.

Samuel says that “those are the sacrifices you have to make if you really care about the story. I don’t regret it, because going there gave me access to the person who was at the mortuary who identified her body, the person who was her French translator – stuff like that. I think that if you hold fast and your conviction is there [then you have to make these decisions], so I just did it. I didn’t think, I didn’t blink.”

Perhaps it is simply a matter of a film’s capacity as a medium to deliver information in a compact, more easily digestible manner than the time-consuming effort of reading that makes Murder in Paris succeed where books like Van Vuuren’s and Groenink’s have failed. Despite its inability to cover in detail all the many theories, red herrings and dead ends surrounding September’s death, the film’s inclusion in the French lawyers’ current campaign to reopen the case is testament to its value.

Samuel says the news is “huge for us, because we didn’t want to simply make a documentary and you watch it and that’s it. We wanted to have a big impact campaign and rollout, and part of that campaign is to roll the film out to schools and communities and [have] Q&As [with a view to] getting the case reopened for the family.”

Murder in Paris, which is being screened in two parts on SABC3, may not find a smoking gun or a definitive answer to the mystery of who fired the five fatal shots, but it might have more success than any other previous attempts to set the wheels in motion for a thorough investigation by French authorities. And it is to be hoped that will help the September family’s decades-long quest for answers.

Even if it doesn’t manage to do that, it should at the very least, as Samuel hopes, ignite a realisation in audiences that first and foremost, before she was a tragic victim of the struggle against apartheid, “Dulcie September [was a] remarkable woman… [and the ANC] was not just populated by all these male figures that we know about today. There were some really hard-hitting women in power who were trying to make inroads into the patriarchy.”