ANDERS KOMPASS

SIX years ago, I became a UN whistleblower, intervening to stop the sexual abuse of children by soldiers in Central African Republic. The revelation led to an independent investigation into how the UN had handled the affair and, in 2015, to a damning report that identified severe structural and systemic weaknesses within the UN system.

At the end of it, in 2016, I resigned from the United Nations, making a final call for structural change in the ethical standards of the organisation.

Since then, I have looked from a distance as Sweden’s ambassador in Central America, still hoping that the UN would learn from what had happened, and change.

Last week, though, The New Humanitarian and the Thomson Reuters Foundation published a one-year investigation into (yet another) sex abuse scandal involving the United Nations.

I read the details with a bone-chilling feeling of déjà-vu coursing through me – the abuse, the denial, the internal closing of the ranks, the excuses, the passing of the buck: It had all happened before. And then a quote from Jane Connors, the UN Victims’ Rights Advocate, perfectly managed to capture all my frustration in one nugget:

“If you are not getting reports, then something is going wrong.”

But who was she talking about exactly?

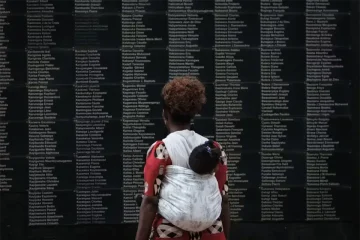

Was she talking about the victims she is advocating for: women coerced into sex by powerful men who dangled money and food before their eyes, money and food that – because of their desperation – could make the difference between life and death for them and their families?

Was she talking about the women who have lived their lives in a quagmire of daily abuse, witnessing the total impunity of murderers, rapists, and corrupt authorities of all sorts – women whose family members had been killed or disappeared by the same police they were expected to report the offences to, or whose sisters and friends had been raped by men wearing the colourful insignias, helmets, and vests of the same international organisations that expected them to drop their complaints through slots on letterboxes?

Or was Connors perhaps referring to other persons – the ones whose bank accounts get credited monthly with thousands of dollars, who come into devastated territories with a return ticket in their back pockets and the knowledge they will never have to denounce a crime at the municipal police station, get treated at a neighbourhood hospital, or sell their bodies for food to the higher bidder?

Or was she talking of the ones who, witnessing widespread abuse, keep silent and only speak anonymously about it when the cans of worms are otherwise opened – because they’re afraid of retaliation by their own organisations?

Yes – something is going wrong and has been going wrong for way too long for the world to still be accepting the trite talk of “zero tolerance” uttered by high officials and managers sitting in comfortable offices in shining skyscrapers.

Those of us who have worked with crumbling justice systems in failed states know that impunity is the cancer that destroys victims – together with the corruption it goes hand in hand with. People do not report to systems they have no faith in because they have seen them repeatedly fail.

And this applies to organisations as well.

Employees also do not report to internal systems they have no faith in because they have seen them fail repeatedly. They have also seen those same systems persecuting, pillorying, and pushing out whistleblowers, while protecting, pampering, and promoting the perpetrators.

They have seen them bungling investigations so badly that these probes have only led to the re-traumatisation and stigmatisation of victims they are supposedly trying to help.

Connors is correct – it is the organisations that are not getting the reports – neither from the victims nor from their own staff.

The investigative journalists and researchers are.

Maybe because they do not wait for victims to walk up to another man in uniform, pick up a phone they do not own, or walk up to an open-air suggestion box when they cannot write?

Maybe because they are seen as independent from the ones who abused them?

Maybe because the victims see their articles and reports making the headlines – albeit it for a few hours – instead of knowing they are being shoved into a drawer only to gather dust and be forgotten?

So, allow me to make a few suggestions for consideration by the United Nations:

- Create an independent body in charge of accompanying any major humanitarian efforts anywhere in the world. Deploy them before the rest, keep them there throughout and let them remain a reasonable time after the others have left.

- Give it sufficient money to invest in prevention, prosecution, safe havens, relocations.

- Give it enough power over your staff to ensure they will be held accountable for what they do. Make the investigation and its results reliable, trustworthy, and transparent.

- Build an organisation within which nobody – ever – shall feel afraid to report abuse. It is unconceivable to ask women to literally risk their lives by denouncing criminals, and to have staff who cannot work up the courage to cross the corridor to report to their supervisor or to the internal investigation office.

Nobody who is not willing to sacrifice something of their life should be working for the UN in its effort to build a better world.

But likewise, nobody within the UN should have to sacrifice their life or career in order to do the right thing.

- By Anders Kompass, a Swedish diplomat, civil servant, and former director of field operations for the UN’s Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

- This oped was written following a joint investigation by the Thomson Reuters Foundation and The New Humanitarian into allegations by more than 50 women of being forced into sex by largely foreign aid workers in the Democratic Republic Congo during the 2018-2020 Ebola crisis.